Alfred Hitchcock’s Best MacGuffins

Grab your passport and bring a sidekick. We're hunting for Alfred Hitchcock’s greatest MacGuffins

This article comes from Den of Geek UK.

Spoilers lie ahead for The Trouble With Harry, Psycho, North By Northwest, To Catch A Thief, The Lady Vanishes, and…Star Wars

The MacGuffin is one of those storytelling inventions that operates by a vague “I know it when I see it” rule. The man who popularized its use, Alfred Hitchcock, didn’t help matters. When asked to define the MacGuffin – as he frequently was – he would repeat the same nonsensical joke.

In Hitchcock’s interview with François Truffaut, Truffaut attempts to establish limits on the phrase (is it “the pretext for the plot”? is it ideally “forgotten” amongst the rush of the action?). Each time, Hitch replies with an answer that amounts to little more than “sort of.”

Without any exact definitions being offered by either Hitchcock or the screenwriter credited with the term, Angus MacPhail, most writing about MacGuffins is dedicated to pinning down precisely what it is.

It is easier to provide examples. The treasure map is a classic MacGuffin. The Golden Fleece hunted by the Argonauts another. They can loosely be linked as specific items to be discovered and/or claimed, but this doesn’t give the full picture.

The Holy Grail of Arthurian legend is often cited as a MacGuffin but, though there is overlap, a grail is its own storytelling device. Grails hold some spiritual meaning for the characters. The MacGuffin is a more material gain, less noble and not to be taken as seriously.

What can be gathered from Hitchcock’s words is that a MacGuffin is an excuse for a plot. It is usually the trigger that springs the plot into action. Without it, there would be no story. In some ways it is the inverse of a deus ex machina. Where a deus ex machina arrives from nowhere to wrap the plot up, a MacGuffin starts it off.

One point on which Hitchcock was clear is that the MacGuffin is unimportant. In the Truffaut interview he insists that while it “must seem to be of vital importance to the characters [t]o me, the narrator, they’re of no importance whatever”. All that is important is that it pushes our characters out of the door and into the story. There are multiple variations on the MacGuffin, but those used by Hitchcock fall into three subcategories.

The Secret

As seen in: The 39 Steps; North by Northwest; Foreign Correspondent; The Lady Vanishes; Star Wars: A New Hope; Burn After Reading

This is the MacGuffin most associated with Hitchcock, with his two most quintessential – the memorized plans in The 39 Steps and the microfilm in North by Northwest – coming under this category. Foreign Correspondent and The Lady Vanishes both revolve around the kidnapping of someone in possession of vital information (a crucial clause in a treaty in FC, a coded message in TLV). Most often found in spy films, this takes the form of secret intelligence which gives one entity – whether a country, an organisation, or a person – power over another.

The Death Star plans in A New Hope also come under this category, though George Lucas himself disagrees. Challenging Hitchcock’s key specification that the MacGuffin be unimportant, Lucas considered R2-D2 to be the MacGuffin of A New Hope, feeling that the audience should care about the MacGuffin as much as the characters do. This carries through to the Indiana Jones films, where the Ark of the Covenant and the Holy Grail end up literally saving the day.

Even the plans for the Death Star, pivotal to the final act, border on being too important. Lucas’ evolution of the MacGuffin creates a grey area between MacGuffin and grail, where objects such as the Ring in Lord of the Rings or Infinity War’s Infinity Stones can also be found.

The Treasure

As seen in: To Catch A Thief; Psycho; The Maltese Falcon; The Ocean’s series; No Country For Old Men; The Pink Panther

The most straightforward MacGuffin. A good rule of thumb for this is to ask whether the item could be swapped out for a priceless rubber duck without any change to the plot. If your answer is yes, then the item is a MacGuffin. Rare art, one-of-a-kind diamonds, and unimaginable fortunes all fall under this classification.

To Catch A Thief has the same “wrongly-accused man looking to clear their name” plot as The 39 Steps and North by Northwest, with diamonds subbed in for secrets. Ostensibly part of Cary Grant’s plan to clear his name, the real story purpose of the diamonds is to bring him into the orbit of Grace Kelly. Once this has been done, the diamonds are relegated to the background. Even the owner is unconcerned about their potential theft, echoing Hitchcock’s own approach to the MacGuffin when she compares her diamonds to “a train ticket that gets me somewhere.” The diamonds get things going, but they’re really not the point.

further reading: The 10 Best Alfred Hitchcock Movies

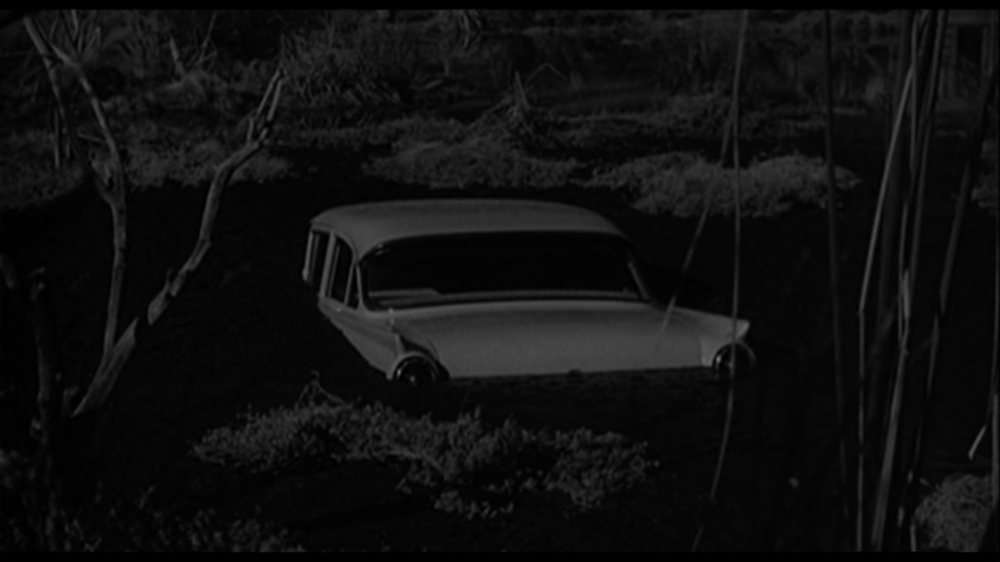

Outside of The 39 Steps and North by Northwest, the most celebrated MacGuffin of Hitchcock’s filmography belongs to Psycho. Easily forgotten by the film’s end, the money stolen by Janet Leigh is what leads to her checking in at the Bates Motel. As in To Catch A Thief the treasure brings the two leads together before being cast aside for more important matters. So incidental is the money in Psycho that an oblivious Tony Perkins sinks it in the swamp while cleaning up the crime scene.

Somewhere halfway between The Secret and The Treasure lies another variant, the ‘Magical Treasure’. In this case, the treasure has one powerful ability which gives it value. Think the Philosopher’s Stone from Harry Potter. Although frequently found in fantasy or science-fiction, this MacGuffin doesn’t have to be magical. The transit papers in Casablanca qualify, as an item that gives its holders the freedom to leave Morocco.

The Character

As seen in: Rope; The Trouble With Harry; The Lady Vanishes; Foreign Correspondent; Saving Private Ryan

The trickiest of the three to identify. For a character to be considered a MacGuffin, they must be both integral to the plot and completely replaceable. In Saving Private Ryan, the story is driven by the mission to rescue a soldier. There is no story without him. Yet, up until the end, that story would play out identically if it were any other soldier in Ryan’s place. His actions don’t factor into it. By this measure, Apocalypse Now doesn’t qualify. Kurtz’s own actions and megalomania lead to Willard being sent after him.

A good rule of thumb is to ask

* Is there still a film if this character is removed?* Do any of this character’s actions affect the plot?

If your answer to both is no, you have a MacGuffin.

Using a person as a MacGuffin is a cold thing, and Hitchcock recognizes this in Rope. Rope opens with two men murdering their friend David, before throwing a party in the apartment where the body is hidden to see if they can get away with it. David – and the body that could be discovered at any moment – is the film’s MacGuffin. Chillingly he is treated as a MacGuffin by the killers themselves, deciding he is “as good or as bad as any other” to be the victim of their experiment.

The Trouble With Harry takes a much cheerier approach to its corpse. The discovery of a dead body in the countryside brings the neighborhood together as they try to solve who he is, how he died, and spend a day alternately burying him and digging him up again to avoid police charges. The characters of The Trouble With Harry treat the body with exasperation, as though it were something much more mundane than a corpse. By the film’s end, it has brought two couples together and everyone (of those still alive) agrees things have worked out pretty nicely.

Finally there’s The Lady Vanishes and Foreign Correspondent. Though listed under the Secret MacGuffin, each has an argument for belonging to this category too. In both, the person carrying the secret is kidnapped and the search for the secret becomes a search for them. Is the MacGuffin the information, or the person in possession of it? The Lady Vanishes makes the strongest case for being the latter. For most of its runtime, the audience has no idea about the code the kidnapped Miss Froy is carrying and nor do the heroes. She is just a disappeared passenger about whom very little is known. It is only after her reappearance that she comes into focus as a character and, ever the professional, only at the end does she reveal the existence of any code.

Unassuming to the point of anonymity, she is the perfect MacGuffin and the perfect spy…

Read and download the Den of Geek NYCC 2018 Special Edition Magazine right here!