How Loki and Fallout Use Retrofuturism to Unnerve Us

Loki and Fallout are two of the greatest examples of how storytellers use retrofuturistic designs as unnerving propaganda.

While Loki has proven to be a somewhat divisive show at times, the one thing that most people seem to agree on is that the series boasts an incredible sense of style.

The same could certainly be said of WandaVision, but unlike that series which wore its sitcom influences on its sleeve, Loki‘s stylistic influences are a bit more varied and complex. Watch Loki close enough, and you’ll spot references and callbacks to everything from Blade Runner and Mad Men to Jurassic Park and Atomic Blonde. All of those styles come together to form a fascinating universe (perhaps multiverse?) where cosmic sci-fi, comic book adventures, and Western action somehow manage to coexist and form a strangely cohesive vision.

Then there’s Fallout. While the video game series that changed CRPGs forever is rarely referred to as one of Loki‘s most pronounced stylistic influences, the two are fascinatingly united by the ways that they use retrofuturism to unnerve us and leave us with the feeling that there’s something so much darker happening in their worlds than the actions of the usual collection of villains.

Retrofuturism: The Advances of Technology With The Comforts of Nostalgia

What is retrofuturism? The technical definition of the term is “the use of a style or aesthetic considered futuristic in an earlier era,” but it’s important to realize that particular definition is based on the idea of looking back. While the “retro” part of retrofuturism obviously implies a look back, many of the most iconic retrofuturistic visuals were actually imagined by those who were, at the time, were trying to predict the future through the concept most commonly referred to as “futurism.” It’s a practice that has existed for centuries even though the idea of retrofuturism wasn’t really popularized until later in the 20th century.

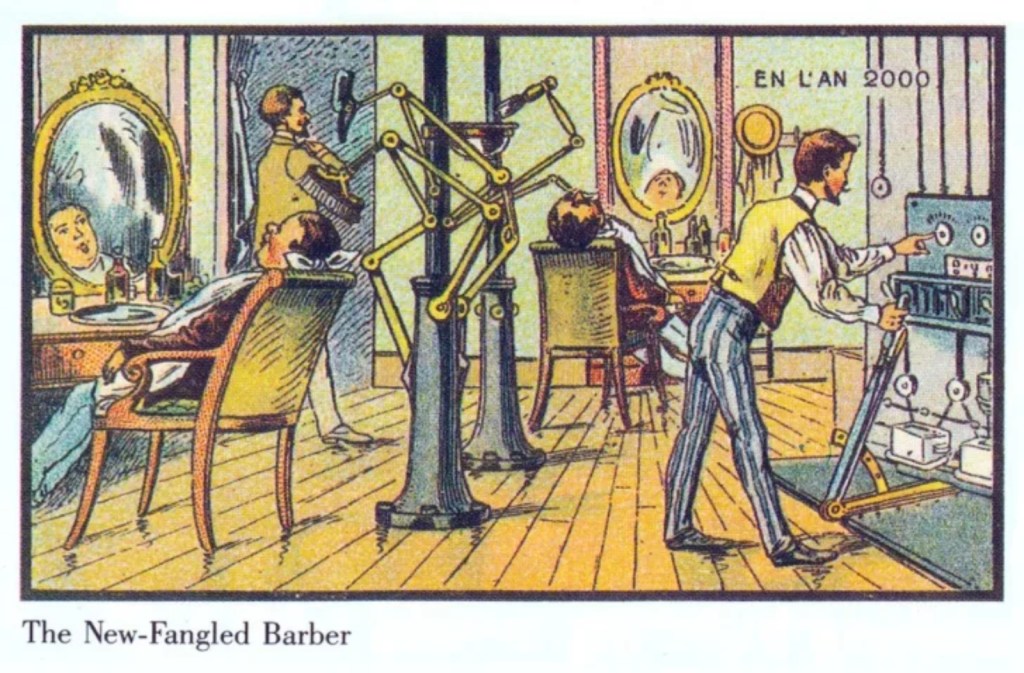

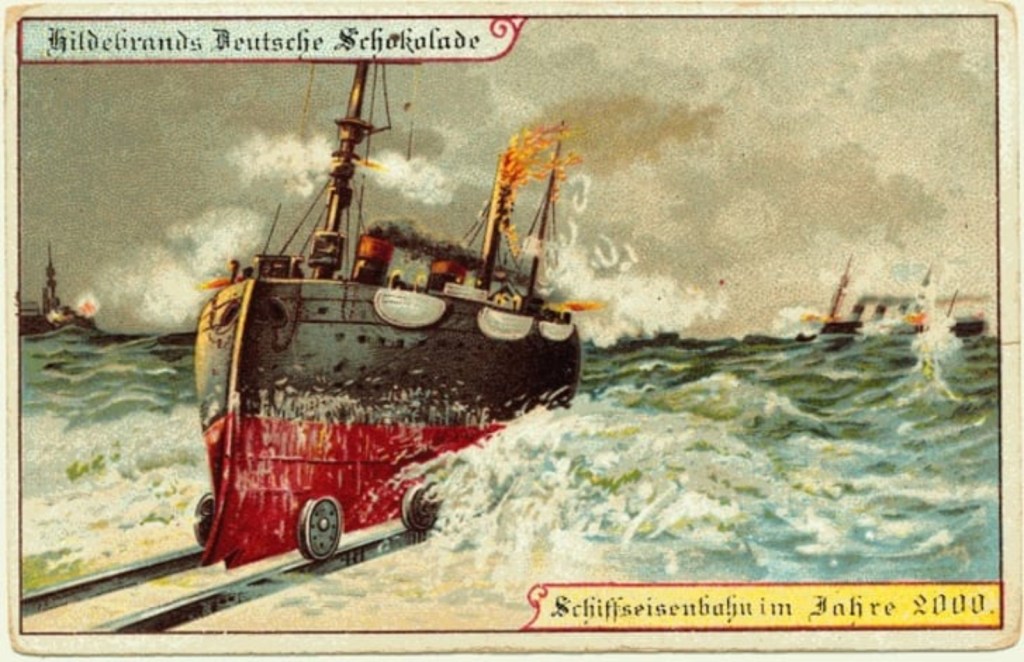

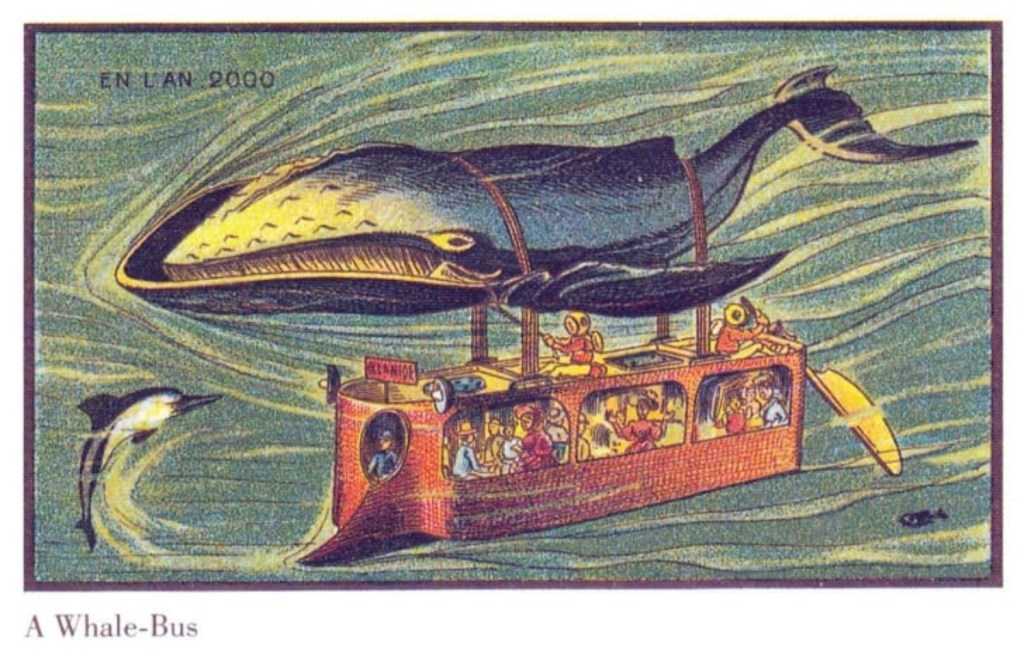

For instance, in the late 1800s/early 1900s, French artists making postcards for tobacco products and a German chocolate manufacturing company took a shot at predicting what the world would look like in the year 2000. As you can see below, their predictions included everything from surprisingly forward-thinking portrayals of automation to utterly bizarre images that make you appreciate just how long opium has been readily available:

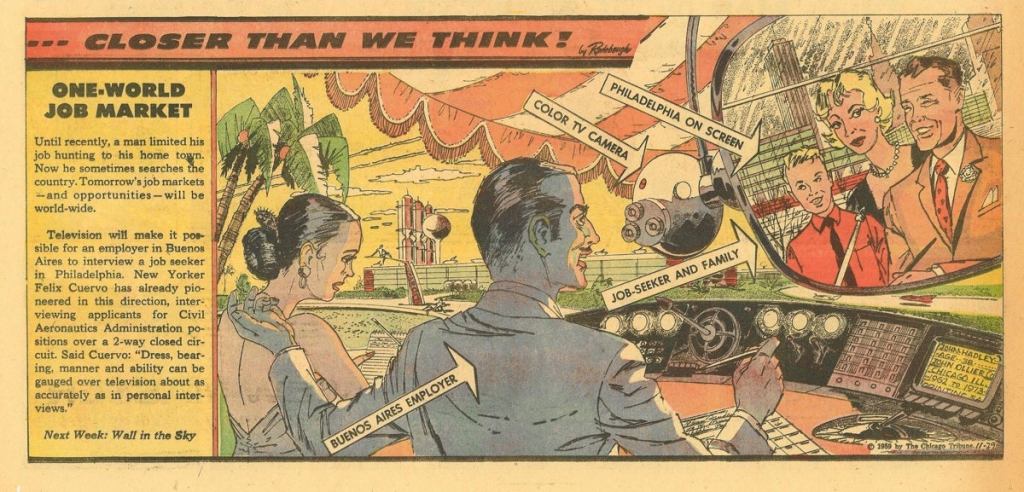

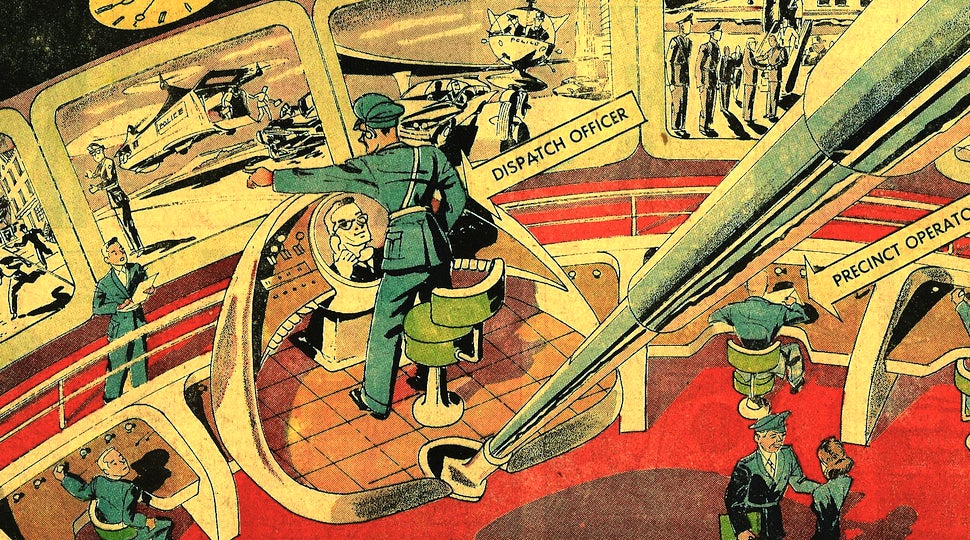

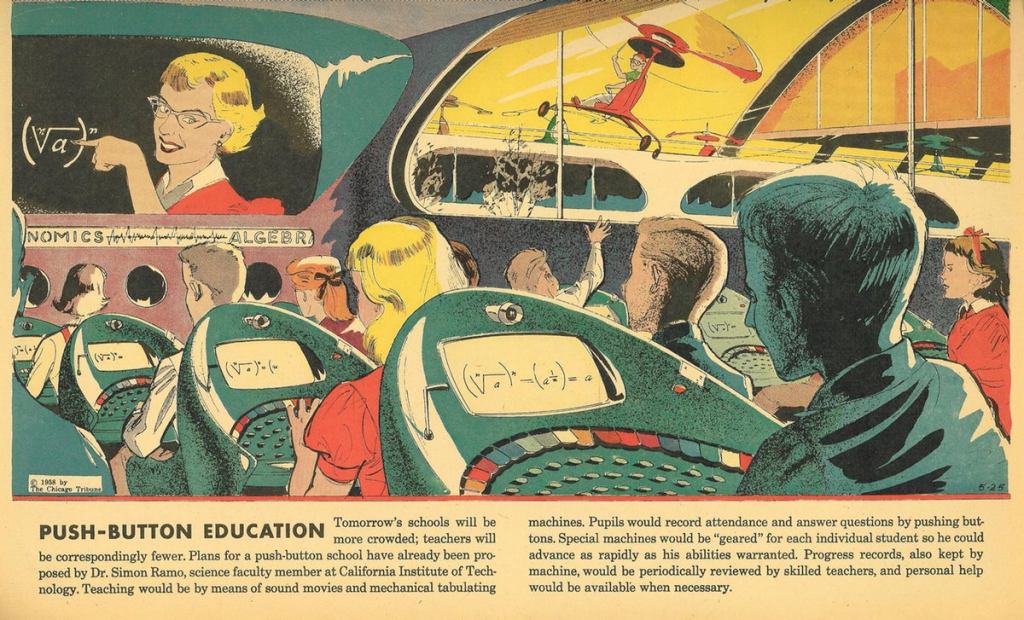

When we think of retrofuturism today, though, we often think back to Americana images from the 1950s and 1960s. That’s when a potent combination of post-war optimism and rapidly advancing technology (especially technology related to the emerging space race) led to widespread interest in predicting just how great the future would be and what it would all look like. While that style can obviously be seen in movies like Forbidden Planet or shows like The Jetsons, some of the most definitive examples of those often misguided glimpses into the future can be found in the old Sunday paper comic strip, “Closer Than We Think.”

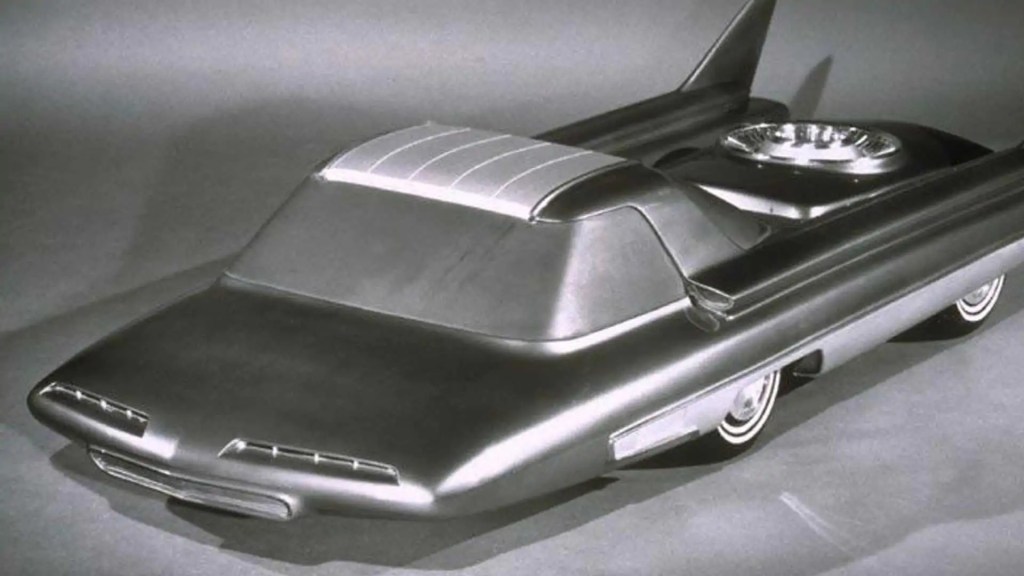

It wasn’t just artists having a bit of fun who were trying to predict the future at that time. There were more than a few manufacturers who were interested in not just trying to advance technology by 30+ years as soon as possible but crafting designs they felt represented what the future looked like. There is perhaps no better visual of this concept than the design of the Ford Nucleon: a 1957 concept for a nuclear-powered commercial car.

In fact, the whole idea of nuclear-powered vehicles was so popular at one point that the United States and Soviet Union each began to research the possibility of designing nuclear-powered jet fighters. The idea didn’t make it far off the ground (quite literally) due to, among many other problems, the realization it would be nearly impossible to shield the plane’s crew from the radiation produced by the engine. Remarkably, the U.S. was so desperate to make the idea work that at least one engineer reportedly suggested recruiting elderly pilots who were going to die soon anyway of natural causes to fly the nuclear planes during the testing phases. The idea was shot down and seemed to be a sobering wake-up call to the realities of the whole idea.

That’s the thing you have to understand about futurism and what eventually becomes retrofuturism. From balloon-powered carriages that won’t break your monocle to the plane of the future that most people of the time would live to fly in only once, the concepts are based on the often mistaken idea that some tenants of society (notably fashion and certain cultural concepts) are going to be roughly the same in 100 years but technology will be significantly improved. The aspects of life that you’re comfortable with now will still be there, but you’ll now have access to an array of conveniences you otherwise couldn’t imagine. It’s all the benefits of technology with the comforts of nostalgia.

Loki and Fallout not only understand the depth of that concept but use it as the basis for horrors that keep us fascinated in their stories and worlds even as we harbor an uncomfortable feeling that we can’t quite explain.

Loki and Fallout’s Retorfurism Design Styles

According to Fallout lore, the world existed pretty much as we know it now until sometime around World War 2. That’s when an event known as “The Great Divergence” occurred.

The basic version of this story sees The United States enter a prolonged period of hostility with China and the Soviet Union during the 1950s as part of a cultural battle against the perceived threat of communism. Much like we saw during our timeline’s version of the Cold War, that period results in fantastic technological advancements born out of both necessity and one-upmanship. An increased desire (some would argue “need”) to harness nuclear power eventually leads to the creation of fantastic machines, incredible weaponry, cybernetics, and advanced supercomputers. It was a kind of new industrial revolution.

However, because these countries were devoting so much of their time and resources to war, their cultures didn’t have a chance to advance far beyond what they were in the 1950s. Even new media that was created beyond that point (mostly comics and radio shows) often drew upon the established style of that era. More importantly, propaganda art remained in vogue as nations constantly encouraged their citizens to join the fight, donate, or do whatever they can in the name of hating and fearing their enemies.

While the early Fallout games played with a somewhat muted version of that concept that accounted for other timeline possibilities, that’s roughly how we arrived at the world that was prominently featured in Fallout 3: a nuclear wasteland where culture and ideas are permanently stuck in the 1950s but technology obviously advanced beyond that time despite looking like it also came from that era (or a vision of the future popular during that time period).

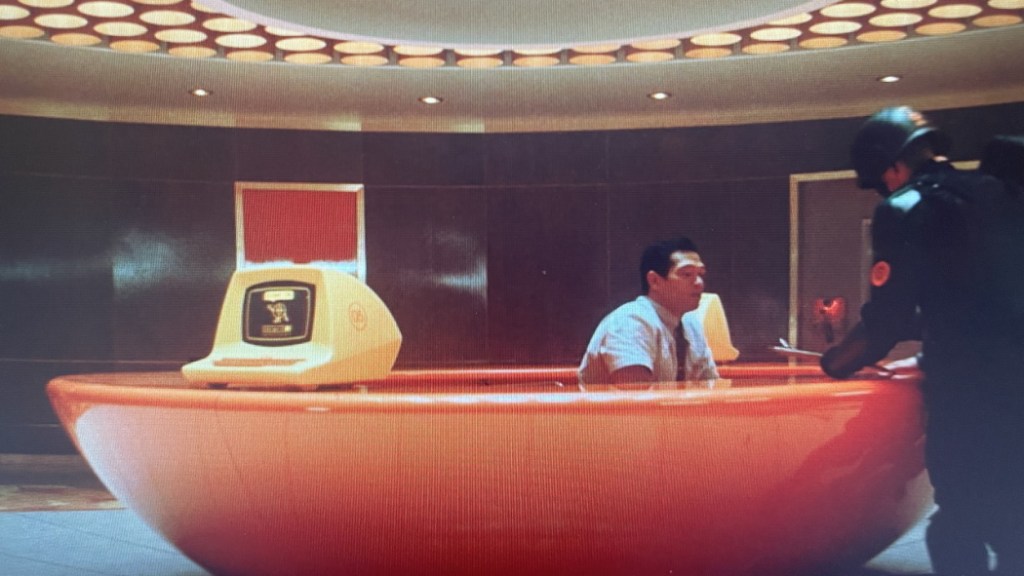

What about Loki, though? Well, while we still have a lot to learn about that show’s lore, there’s no denying that the TVA utilizes a distinct retrofuturistic style where unbelievable technological advances clash with surprisingly outdated hardware and cultural concepts. From a lore perspective, Loki director Kate Herron has noted that the design is meant to convey the idea that the TVA is stuck outside of our ideas of a traditional timeline and pull from both the past and future due to the constant chronological confusion they inhabit. From a style standpoint, Herron has also cited titles like Blade Runner and Metropolis as some of the series’ biggest influences when it comes to the retrofuturism look of the TVA offices.

Herron has seemingly never referenced Fallout as one of Loki‘s major stylistic influences, which is actually quite surprising given some of the design similarities the two series sometimes share.

Mind you, none of this is meant to suggest that Loki somehow “rips off” Fallout or that the series’ showrunners owe the game series any kind of acknowledgment. In fact, both draw from the same well of cultural influences, which happen to include those real-world retrofuturistic designs that helped popularize the concept in the first place.

No, what really interesting about Loki and Fallout’s retrofuturistic connection isn’t their shared visuals but how each uses this concept to create a world that is strangely alluring even as we realize the whole thing is built on lies.

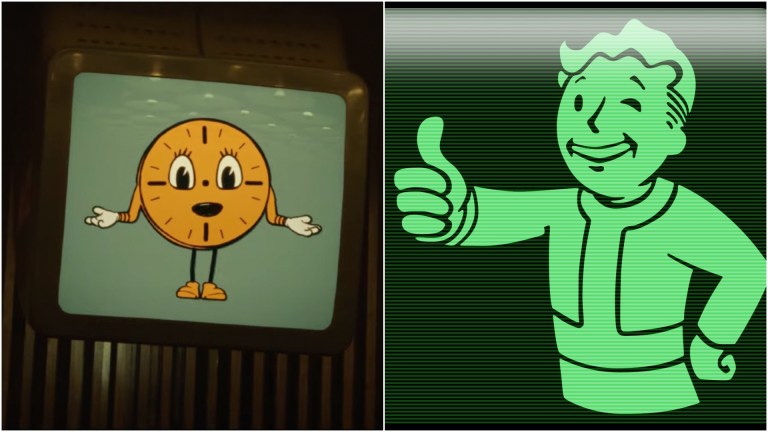

Vault Boy and Miss Minutes: The Smiling Faces of Bureaucracy, Corruption, and Propaganda

In the world of Fallout, we have the “advantage” of coming into its retrofuturistic world at the end. When you see an old drawing of a smiling family asking you to buy war bonds as it’s being stepped on by a super mutant created from the fallout of the nuclear war those bonds were used to fund, it’s hard to miss the social commentary.

Yet, Fallout’s design isn’t solely intended to be an ironic backdrop to the apocalypse. Actually, Fallout‘s vision of the end of the world can be traced back to the cultural institutions that popularized that retrofuturistic style that initially seems to clash with the game’s vision of the apocalypse.

There are few better examples of that idea than Fallout’s mascot: Vault Boy. Designed to be the poster child of the Vault-Tec Corporation, Vault Boy was supposed to be a friendly face that distracted people from the fact that one of the largest companies in the world only exists because a never-ending war necessitated the privatization of fallout shelter creation. Vault-Tec was given the power to do pretty much whatever they wanted in the name of rapidly advancing the development of technology that was supposed to help people. Mostly, though, they want you to remember them for that smiling character that assures you that everything will be fine, despite the fact that everything can’t be fine if a company that offers such a service has already become as powerful as they were.

Well, Loki has its own Vault Boy in the form of Miss Minutes. We first meet this cartoon clock when Loki watches an instructional video designed to help inform variants what the TVA is and why they are there. The video (which was clearly inspired by retro PSAs and commercials) is a horrifying revelation that strongly suggests that free will may not exist just as it implies that the universe is only being held together by largely absentee gods and the bureaucrats that serve them. Who better to deliver that kind of information than a cartoon character designed to make you remember times when you never thought about fate and the finite nature of life?

In both cases, retrofuturistic design principles are used to shield people from the harsh realities that birthed them. Vault Boy isn’t worried about nuclear war, so why should you be? Miss Minutes isn’t suffering from existential dread, so why should you? They’re creations pulled from a different era as a way to say “Hey, if this whole situation is as bad as you think it is, then what is this smiling character from a simpler time still around?”

Of course, it’s all a facade. Fallout and Loki (and Terry Gilliam’s brilliant Brazil, for that matter) show us worlds where the bureaucracies and corporations wear the faces of our own nostalgia. They have successfully harnessed the optimism of a more innocent time that never really existed in the way they suggest it did. That image they created only becomes stronger as it is reinforced by a new generation that defends a time and ideas they never knew because they were raised to believe in a carefully crafted version of them.

Again, though, in both Loki and Fallout, we have the advantage of coming into these worlds from the outside. We know they can’t exist because they’re not our own. Yet, there is something deeper and more sinister about the use of retrofuturism as a thematic whistle that goes well beyond the borders of fictional worlds and makes us reexamine how we view our own.

Retrofuturism Tells Us That We’re Somewhere We Don’t Belong

There is a genuine appeal to retrofuturism from a sheer stylistic standpoint. There’s something strangely satisfying about watching complex tasks be performed by old computers or seeing one of the cars that defined Americana be launched into the sky as a family prepares for their vacation to the moon. It’s wonderfully absurd and, especially in the case of Loki, it gives personality to what may otherwise be a dry and lifeless office environment.

Yet, retrofuturistic design is still based on the idea that the scary and uncharted world of tomorrow and all the technological advances that come with it can be tempered by a dose of nostalgia. It tells us “the future will be the best of all worlds” when we know (or should know) that technological advances change society in ways both good, bad, and, most often, something in between. In the 1950s and late 1800s, people used futurism to dream of what wonders the future will hold. In 2021, we often use retrofuturism as a way to mock some of those predictions while still sometimes fantasizing about this time when there seemed to be widespread cultural optimism about the future.

It’s hubris that leads us to believe we can predict or control the future, and it’s hubris that’s at the heart of retrofuturistic design. While there are some who would undoubtedly want to live in a world filled with ‘50s/’60s designs and cultural values where they are still able to enjoy certain modern technological conveniences, even the most hopelessly nostalgic must see the retrofuturistic worlds of Loki and Fallout and think “this isn’t right.” Retrofuturistic design done well is one of the best ways to convey that something has gone horribly wrong before we even know what that something is. Loki and Fallout happen to be two of the better examples of retrofuturistic design utilized exactly for that purpose.

As writer Bruce McCall once put it, retrofuturism is sometimes nostalgia for a future that never happened. It’s that old Air Force engineer looking at a black and white photo and thinking “If they had just let us put senior citizens next to nuclear reactors, we’d have better planes by now.” It’s fascinating to look at, it’s interesting to think about, but as Loki and Fallout show us, it’s nearly impossible to spend any time in such worlds without realizing that they’re rarely more than pretty lies.