How Halloween Night Punk Rock Chaos Created SNL’s Most Notorious Moment

40 years ago, a Halloween SNL appearance from hardcore punk band Fear left a wrecked stage and shocked censors, leading to a ban.

“They’re really nice people, you know. [Laughs] They look very frightening, but they’re really very nice.”

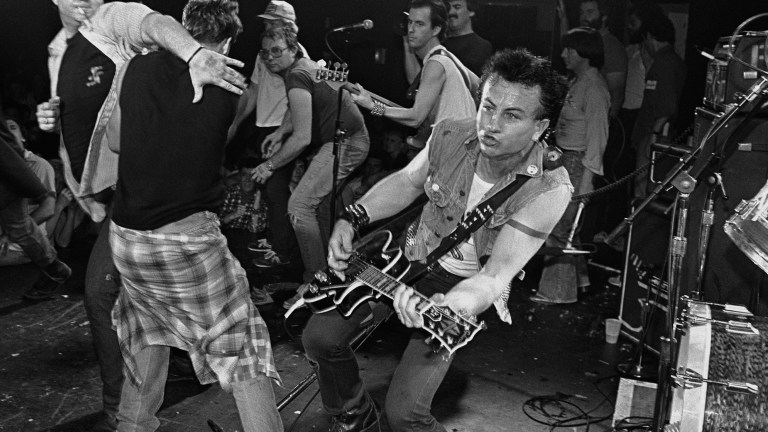

That compliment, dubiously delivered on Saturday Night Live’s 1981 Halloween episode by a thematically-apropriate host in Halloween star Donald Pleasance, served as the introduction for the show’s most unique musical act: SoCal hardcore punk rock band Fear. However, differing from other “controversial” moments in the show’s history, Fear’s appearance remains notorious not for the content of their music—rough around the edges as it was—but for the wanton destruction it left onstage, and an abrupt admonishment of the show’s sacred metropolitan setting.

With Halloween having fallen on Saturday in 1981, that evening’s episode of SNL needed to bring something spooky and/or disturbing to the table. Consequently, the atmosphere had become amenable for the national television debut of one of the loudest, rudest, and crudest punk rock bands on the surging SoCal scene, the aptly-named Fear.

The L.A.-based band, coming off a prominent showcase in director Penelope Spheeris’s epochal 1981 documentary, The Decline of Western Civilization, had just signed with Slash Records, and were ready to take on the world. However, the very sight of the uncouth quartet in front of a spray-painted background logo left unacquainted viewers doing a collective double take, especially when slam-dancers stormed the stage as singer Lee Ving belted out “Beef Baloney,” a song that, rest assured, is not a touching tribute to cured meats.

Check out Fear’s notorious 1981 Halloween night SNL performance just below.

Contextually, SNL, having existed rudderless during its preceding season, was finally on the cusp of a second Renaissance going into Season 7 (1981-1982) with a mostly-new, more-refined cast spearheaded by the presence of future cinematic superstar Eddie Murphy. Yet, the show was hardly the fine-tuned (some might say perfunctory) machine it is today, and newly-appointed executive producer Dick Ebersol was still throwing concepts at the wall to see what stuck.

Consequently, an unlikely greenlight was granted when distinguished cast alumnus John Belushi pulled some strings to compensate Fear after a theme song they recorded for his 1981 comedy movie, Neighbors, ended up unused in the film. The deal was sealed, since newly-appointed head writer Michael O’Donoghue—himself a former featured player—was as much of a fan of the band as Belushi, and allegedly told an uninitiated Ebersol that Fear was simply a pop group, like The Carpenters.

Getting back to the performance, the band’s unsubtle, phallic-minded opening number would be followed by derisive banter from a shirtless Ving, starting with “Thank you very much. It’s great to be here in New Jersey,” designed as a regionally-esoteric way to rile proud New Yorkers. That set a wrestling-heel-type tone as the rest of the band followed suit with sarcastic salutations, notably as blue-dress-donning lead guitarist Philo Cramer handed out bills to the close-situated crowd, saying “I’ll give you a dollar if you’ll be my friend.”

Yet, even that routine was just a preamble for the further antagonization of the Big Apple audience with the mocking music number, “New York’s Alright If You Like Saxophones.” However, as the onstage anarchy continued, audio started to spill over—not from Ving’s coarse lyrics, but from the moshing stage-stormers, as phrases such as “Fuck you,” and “New York sucks” could be heard over the live network broadcast, to which Ving disingenuously responds, “We’re just kidding, we want to make friends.”

The ongoing cacophony and complementary onstage freneticism provided by the slam-dancing fans closely positioned to the small stage was something the likes of which network television had yet to showcase. Of course, it was already old hat for fans of the burgeoning hardcore punk scene, and the slam-dancers themselves were actually a curated coterie of prominent punk figures, specifically bussed in from the surging scene in Washington D.C., notably Minor Threat frontman Ian MacKaye, who, besides being credited for popularizing punk’s drug-and-alcohol-free “straight-edge” segment, would later go on to form the better-known outfit, Fugazi.

Indeed, this was hardly a rabble of randos rounded up from the streets, and was designed to present a snapshot of the still-underground punk rock scene that was only recently revealed to the rest of the world in Spheeris’s film. The rest of the group consisted of Minor Threat band members, along with Tesco Vee of The Meatmen, John Brannon of Negative Approach, and Harley Flanagan and John Joseph of The Cro-Mags.

As Ving recounted of the genesis of the destructive slam-dancers becoming part of his band’s SNL performance in a 2015 interview with Talk Show with Simon Harper, “Somebody who had been in the audience at [John Belushi’s] behest [called] Washington D.C. [about] having some bands with some people—it was supposed to be 15 people—come up to New York to the studio to be [an] audience. [An] actual punk rock audience, rather than Mr. and Mrs. Missouri. So, by the time they get to New York, there’s not 15 people, there’s like 80 of them, and when they ushered them in and I’m beginning to sing [Beef Baloney], somebody grabs a mic and says ‘Fuck New York!’”

Obviously, the segment had gone far off the rails by that point, and panic set in behind the scenes as Ving proceeded to offer a bit of political nihilism aimed equally at Democrat and Republican suburbanites of voting age before going into what was to be the band’s third number, “Let’s Have a War,” which now stands as their signature song, and would notably become included on the soundtrack to the irreverent 1984 cult classic action film, Repo Man. However, the expected panic in the control room had substantially manifested, since the broadcast would abruptly cut to a commercial break about 16 seconds into the song. This, according to Ving, occurred after a frantic phone call from legendary NBC primetime architect executive Brandon Tartikoff, who ordered the segment to be yanked off the air immediately.

The blowback from Fear’s performance was quickly felt in the New York City news cycle. The primary driving force behind that was a New York Post article that bore the headline, “Fear riot leaves Saturday Night glad to be alive!,” which claimed that the demonstrably-violent stage antics endangered the crew and caused $200,000 worth of damage to studio equipment. While the veracity of the report was mostly upheld, the dollar amount for the damage in question—initially believed to be only $10,000—became the center of confusion caused by Ving himself, who was feeling mischievous when called by the Post reporter for confirmation of the figure.

As he explains, citing an even higher number than the Post story, “So, after the show, on the Sunday after the Saturday night, I get a phone call at the Four Seasons [Hotel], and they said, ‘Hello, is Lee Ving there?’ and I said ‘Yes, that’s me, who’s this?’ They said ‘This is so-and-so from the New York Post, and we have it on good account that you caused $10,000 worth of damage to the studio at Rockefeller Center last night on NBC’s Saturday Night Live.’ I said ‘That’s a bold-faced lie, we’re professionals. We caused $400,000 worth of damage to the studio. I counted it myself.’ They printed it, and I got tagged with 400K worth of damage to Rockefeller Center! What could be better?”

Naturally, the incident would leave the band persona non grata on SNL—or any other NBC outlet for that matter—bestowing the band a stigma of instability that Ving still wears with pride as he states, “I got banned permanently. That’s sort of an honor in its way.” Indeed, the notoriety served as the perfect catalyst for the May 1982 release of Fear’s first full-length album, minimally-titled “The Record.”

However, the band would never quite break into the mainstream, even amidst the fertile music video soil being sowed for bands during the heyday of MTV. Yet, it would not be unreasonable to theorize that Fear’s performance ended up shying away MTV and other corporate media outlets from the hardcore punk genre; a status that remained unchanged even in the post-Nirvana Alternative Rock boom of the ’90s. In fact, the performance’s blowback would directly cost another prominent member of the SoCal punk scene, Black Flag, who had been booked for an SNL performance only to see that prospect subsequently cancelled.

Notwithstanding a bevy of lyrical content that today would be deemed—perhaps rightly—offensive or, in the very least, comically juvenile, Fear remains regarded as one of the most important, frequently-evoked American punk rock acts of the early era. In fact, Grand Theft Auto V, one of the best-selling video games of all time, immortalized one of their most notorious numbers, 1985’s “The Mouth Don’t Stop (The Trouble with Women Is)” on nostalgic punk radio station Channel X, where its parody-level misogyny bolsters a playlist evocative of misanthropic playable character Trevor Philips, for whom the station is a default.

That seems to be the showcase gift that keeps on giving, especially since the game continues to be re-released nearly a decade after its initial 2013 debut. And as for the possibility of a Fear/SNL reconciliation: Don’t hold your breath.