“I Had Tears Running Down My Face”: Neil Gaiman on The Ocean at the End of the Lane Stage Play

Neil Gaiman’s beloved book has been adapted for the stage, in an exclusive interview Gaiman talks about the power of the immersive experience.

This article is sponsored by The Ocean at the End of the Lane. Want to win tickets? Click here to enter our giveaway!

Neil Gaiman’s The Ocean at the End of the Lane is a fantasy novel about a child that comes into contact with a mysterious and dangerous other world, and what happens when something from that world makes it back and infects his own life.

It has a lot in common with another of Gaiman’s books, Coraline. But while Coraline is a children’s story, where if you are clever and brave you can beat the monster and save the day, The Ocean at the End of the Lane is childhood seen through an adult lens. It is a story which knows that to be a child is to feel helpless, and that this feeling is often justified.

It’s also a story about memory, and how unreliable and changeable, and suddenly unexpectedly powerful it can be.

Translating a story like that to the stage is a daunting challenge, but it is one that the National Theatre, London has pulled off admirably. We talked with Neil Gaiman about seeing his work translated to the stage, and the magic of theatre.

You have said when the play was first suggested to you, you thought the book would be impossible to stage. Obviously you’ve changed your mind since then, so what is it about the book that you think suits the stage in particular?

It’s interesting because the book is about a number of things, but one of them is memory. And I think that one of the things that Joel [Horwood, scriptwriter], in his script, and Katy [Rudd, director], in her staging, gave us is a way of looking at memory. You are moving through somebody’s memories. You know that they’re not necessarily accurate. They may be, but you also know that things have been playing around with these memories. So, whether they’re accurate in one way or whether they’re accurate in another, you don’t know.

But there’s a sort of a wonderful way that instead of feeling like you’re moving from scene to scene, or set to set, you’re flowing with memory and everything is changing around you.

The entire book is from one person’s point of view. That’s not something that I would’ve thought would make it easy to stage. [The narrator] is barely off stage. He’s there and the world forms, and shapes, and moves around him.

It’s a lot of heavy lifting from a staging point of view. It’s actually doing stuff that occurs inside people’s heads. And that took me by surprise. For me, a novel is a way to do something inside somebody’s head, but a play is a way to make them part of an audience. They’re experiencing something huge and magical all at the same time. And you sort of go, okay, I know that these are not real people. I know these are actors, I know I’m in a theatre, yet somehow I’m allowed to access that part of my brain that says this is also real.

What was it like seeing your book on stage?

There’s a very weird way in which Ocean, because it taps into memories that are so primal, I think also manages somehow to tap into emotions that are primal. I was astonished the first time I saw a complete run-through and realised I had tears running down my face. I was astonished and embarrassed, because I wasn’t sitting there in the dark quietly on my own. I was in a well-lit rehearsal room with all of the actors checking me out all the time, going, “What’s he going to think? Is he going to like this?” And I’m trying to discreetly flick away the tears.

Since then, I’ve sat there next to a reporter on the first night in the National Theatre and watched this guy’s notebook getting splashed by tears. And I thought, okay, whatever it did to me, it’s doing to him, and he’s sat there with the same experience going on.

The last time I saw [the play] at the Duke of York’s Theatre I was finding different places that I was crying, going, “This is so weird. I know how this story works. I put it all together. I built it from scratch. And yet it’s affecting me in ways that are primal, and deep, and emotional.”

How was the decision made to portray the creatures in the story as puppets?

The puppets, and the puppetry, were there from the beginning. When Katy and Joel pitched me on doing the show at the very, very beginning they really knew what they were doing.

The one thing they were sure of was giant puppets made of rubbish. That was there from the word go. The puppetry department, the puppet creators and inventors, it was one of the leaders of that team who was the person who first showed the book to Katy and said, “You should do this.” So, the puppetry was intrinsic from the beginning.

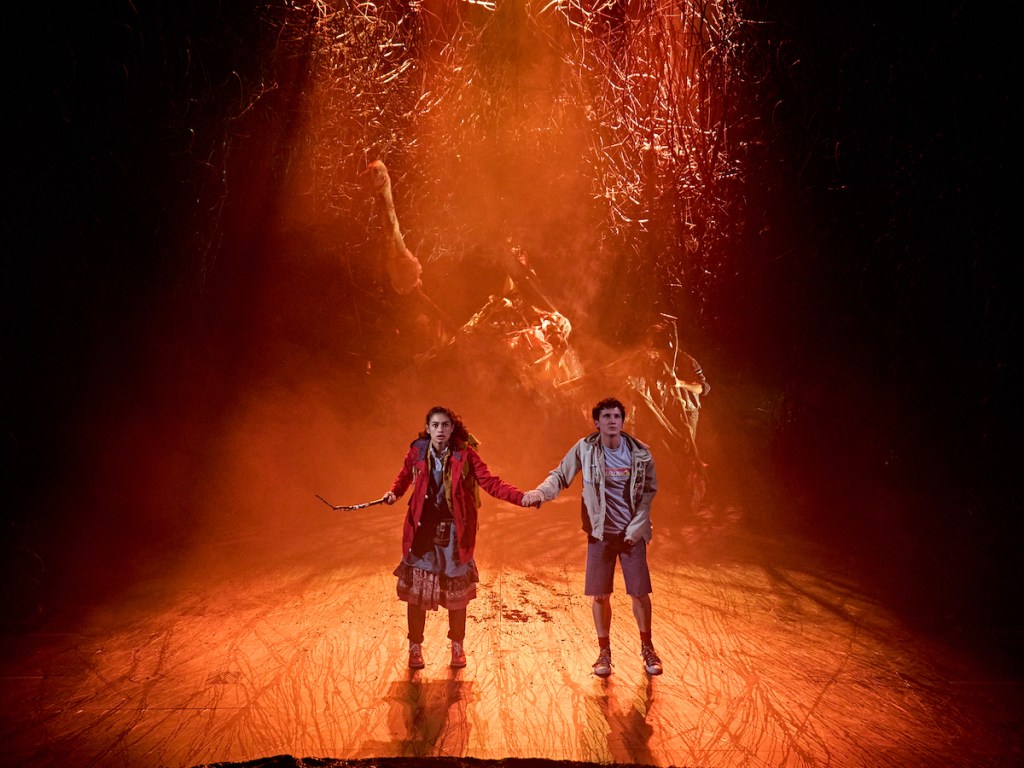

But I did think the puppetry, for me, is like everything else in Ocean, in that the ragged-edged slightly amorphous nature of it fits with memory and works in a lot of ways. You look at the Deviants in The Eternals, and they’re these elegantly delineated, monstrous creatures, but there’s nothing unknown or unknowable about them. Whereas you look at Skarthach, or you look at the Hunger Birds, and everything about them is unknown and unknowable, but they are terrifying, nonetheless.

You’ve seen your work adapted into a lot of different mediums, and you’ve got several adaptations going on this year. How does having your work adapted for stage differ from, say, screen adaptations?

Well, one way it differs is that every performance is different. No two audiences are going to ever see the same thing. I remember years ago, the National Theatre of Scotland did The Wolves in the Walls. And for me, the second preview in the Tramway Theatre was the best. It was terrifying and funny.

And then everybody got nervous, and they dialled down the terrifying and all of the things that had been really scary in the second preview. And I kind of understood it- they didn’t want pools of little kid wee on the floor. But there was a level in which that thing that happened that night for me was The Wolves in the Walls. And every other time I’ve seen it, I go, “Oh, it’s good. But that night was special.”

But theatre, I think, is much more malleable. It’s weird because one of the things I love about theatre is you are only making decisions that apply to that performance that night. And when you decide something like casting for film or TV, you are seen as making huge political decisions beyond the ramifications of just, can I find somebody who’s going to give me that thing that I’m looking for? Whereas with theatre, or especially the kind of theatre that that Ocean is, it’s kind of understood. You’re telling a story. You’re telling that story that night, right now, with actors, and it’s okay. And I kind of enjoy that.

But I also really enjoy just the immediacy. I have been happier at the theatre than I have ever been at the cinema just in terms of joy.

What are your childhood memories of the theatre?

At age three, being taken by my aunt, Diane, to see Iolanthe at the Kings Theatre in Southsea. The Kings Theatre in Southsea was where I went and saw pantos. We’d go down and see my grandparents, and they would take us to the panto.

Getting up on stage singing “Old McDonald had a farm”, being, I think, a pig, and being given a box of chocolates as I got off was probably the highlight of being four. Nothing has been quite as good as that ever since. Even when you get Hugo Awards, you’re like, “It’s good, but it’s not a box of chocolates for making an oinking noise.”

When I turned about eight, maybe seven, eight, nine, somewhere in there, I was obsessed by Gilbert and Sullivan. And my parents would take me, once a year, maybe even twice a year to the Savoy Opera, at the Sadler’s Wells in London. And the lead was a guy called John Reed, who I believe is now probably long dead, but he was the fourth or fifth in line since George Grossmith, who was the one that Gilbert had trained as his leading man, his comedian. And I just remember the joy of Ruddigore, the joy of The Mikado. That for me was far and away the best.

How is the play being adapted for the national tour?

I love that Katy has this new challenge of reinventing it for theatres where you can’t cut your trap doors where you need them, and all of the things, some of the amazing effects that they pull off, and they’re going to have to do it with what they’ve got. But I love that, knowing Katy, she’s viewing it as a challenge rather than as an obstacle.

You talked about thinking the book was impossible to stage, but you also said you trusted the team looking to adapt it. Could you tell us where that trust came from?

A lot of it started with the very first meeting. I just remember going in and meeting them. The National Theatre has some rehearsal runs next door to the Old Vic Theatre, and I went there, met them, and just liked them and trusted them.

And Katy had something about her that I recognised. There’s something really fun sometimes where you get people who are monumentally talented but have not yet been given their big break, their big solo thing, and they have a lot to prove. And I thought, “Oh, you are one of them. You’re ready now. You’ve been quietly working away in the background on other people’s shows and playing an incredibly important part. You want your own show now and you want to show people what you can do.” So, my confidence in Katy was enormous.

With Joel, it was more a matter of just that lovely, creative to-and-fro. Every six months, every eight months, I would go to a read through. And after the read-through, I’d give him notes and I’d say, “Okay, this works, don’t change that. This bit doesn’t work. It’s too big. It’s too weird. This bit just feels lumpy for me. If you do this, then you are losing that, but I can see that you gained this.”

But I genuinely didn’t know that it was going to work until I saw my first run through. I was perfectly ready for it to be, not a complete failure, because you never see complete failures, but I’ve had things in the theatre where I was excited and then I saw the finished thing and it didn’t work for me.

There was that adaptation of Coraline off-Broadway, where I loved the people involved and yet nothing seemed really to work. And it was the kind of thing you walk out of going, “Hmm. That was very good.” rather than walking out going, “Oh my God, my life has changed.”

And that’s what I love about what Joel and Katy, and the actors, and the team have pulled off, and it is the whole team. It’s the lighting, it’s the set design. Everything works, everything contributes to you walking out, going, “I am not the same person I was two and a half hours ago before this thing began.”

Before we go, how are Sandman and Good Omens 2 going?

Well, Sandman is pretty much done. The trouble is, you say pretty much done and that means everybody starts checking their watch and going, “Why isn’t it on the screen right now?” And you’re going, “Well, yes, it’s pretty much done, but…”

The amount of VFX stuff on Sandman is comparable to ten major Hollywood VFX movies. This thing is huge, and the VFX is huge. So now it’s all done, and computers are still rendering things, but basically, it’s done. It’s shot, and it’s amazing.

Good Omens is shooting currently, and I’m living the strangest sleep schedule I’ve ever had. As soon as I get off the phone with you, I’ll be getting on the phone with the director who will have knocked off for the day. He’ll be waiting to talk to me about what he shot that day and today. And I tend to watch what they do until about one o’clock in the morning, my time. And then they carry on shooting from one o’clock in the morning, which is their midday, so for their afternoon they’re off the leash and I find out what they shot in the afternoon a day later when it turns up on my apps.

It’s amazing. It’s so funny, it’s so moving, it’s so like, and yet, unlike anything that you’d expect. It’s got all sorts of different flavours, and it’s also amazing because Michael Sheen knows Aziraphale now, inside and out. And David Tennant knows Crowley. And on the one hand, we’re bringing back actors, and on the other hand, we’re bringing back characters, and everybody knows what they’re making. And it’s so much nicer to have our Soho street built in Scotland rather than having it built on a disused airfield in Bovingdon because it’s an awful lot warmer and more comfortable for everyone. And we don’t have to stop when it snows.

The Ocean at the End of the Lane is showing at Duke of York’s Theatre in London until 22 May 2022. Want to win tickets? Follow the instructions below!