Laurel Canyon: The Byrds’ Chris Hillman Gives Rock and Roll Stardom Tips

Chris Hillman helped The Byrds find folk and country rock sounds in the studio, and a home in Laurel Canyon.

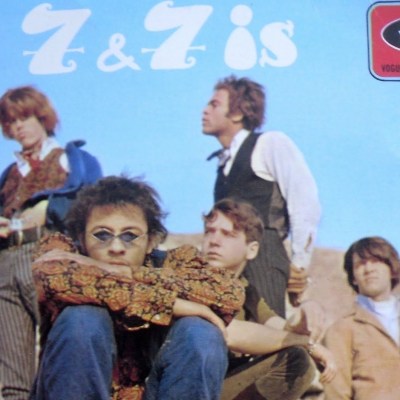

Laurel Canyon, the two-part docuseries Alison Elwood directed for Epix, opens as the Los Angeles folk music scene went electric and The Byrds found a place to nest. Rock and roller Bobby Darrin put a backbeat to folk tunes in the early ‘60s, but his then-guitarist Jim “Roger” McGuinn transformed the genre into folk rock by electrifying Bob Dylan songs with an electric 12-string Rickenbacker when he formed the Byrds. The band, which also included future David Crosby, Gene Clark, Michael Clarke and Chris Hillman, was known for a short while as “The American Beatles.” The Byrds put out one of the first psychedelic rock songs, and went on to create country rock.

They were also one of the first groups to move into the woody enclave above Los Angeles’ Sunset Strip, starting with their then-19-year-old bass player. They would soon be joined by The Monkees, The Mamas & The Papas, Love, Buffalo Springfield and other musicians who turned Laurel Canyon into an artistic Shangri-La for a new generation of players. Collaborations happened, bands formed, and sometimes restructured within the small community. When Crosby was fired from the Byrds, he found Stephen Stills and Graham Nash within walking distance, and the band found Gram Parsons.

Chris Hillman was playing mandolin in country and bluegrass bands before he joined The Byrds. He brought a melodic bottom to the band’s foundation, flawless harmonies and original songs which went on to become rock anthems. “So, you want to be a rock and roll star,” he asked in the song of the same name, and gave step-by-step instructions. He and McGuinn even visited Stonehenge with two of the Rolling Stones, and knew enough to get out of their Altamont rock festival as soon as he unplugged his cable from his amp. Hillman went on to found the Flying Burrito Brothers with Parsons, joined Stephen Stills’ band Manassas, formed the Souther-Hillman-Furay Band with J.D. Souther and Richie Furay, and the progressive country group the Desert Rose Band.

Chris Hillman spoke with Den of Geek about his bands, bass, and the canyon which created the California sound.

DEN OF GEEK: The Byrds created folk rock and they created country rock. So did you know you were creating genres when you were doing it, or was it just fun music to play?

CHRIS HILLMAN: We were just following our instincts. I mean it sounds corny, but we were following our heart. We came out of folk music, and me more so out of bluegrass and traditional mountain music. It was quite a move just to plug in amplifiers. We really took what we had been doing and put it together, especially with “Mr. Tambourine Man” when we got a hold of that song. Bob Dylan had written that in more of a country feel. Roger McGuinn put it into a 4/4 feel where you could dance to the song, which is really what got it to happen for us. No, we weren’t aware of that at all. Never. Even when we started to do, say country rock. Before that, what do we have? Folk rock and then psychedelic rock.

“Eight Miles High” is one of the beginnings of psychedelic rock.

It is. Yeah. To me, it’s a jazz song. I thought that’s what I loved about The Byrds. I was very lucky to be in that group. I got to tell you, I was blessed. Because here we go. We start out emulating the Beatles. Then we cover Bob Dylan stuff. Go back to “Turn, Turn, Turn” which is Pete Seeger taking Old Testament scripture and putting music to it. Then, we get to the point of doing songs like “Eight Miles High” and “So You Want to Be a Rock and Roll Star” and stuff like that. We really turned into a great band. I’m biased, but here’s the deal. What The Byrds and what they created all around that period, back to our topic of Laurel Canyon, it held up through the decades.

A lot of times we cut some pretty silly songs. Everybody does that. We’re all guilty of stepping out and recording something that isn’t going to hold up. We did make some great music, and it’s held up for 50 years, it’s still going. That’s a good thing. We left a great path for everyone else. So when The Byrds first started, and all the other bands came along later, most of them did come from the same place, from folk music. Mamas and Papas, Buffalo Springfield, Lovin’ Spoonful, I’m sure they saw what we did. They went “okay,” and did the same thing. Did it as well or better, a lot of times better.

And it is all connected to where we were living. Roger McGuinn and David Crosby and I lived within a half mile of each other in Laurel Canyon. I think we were several of the first ones up there. Then, bands started moving up later. I was only there from ’65 to ’68. My house burned down where I was living and I moved up to Topanga Canyon, which was about 30 miles north of LA. A little bigger area, but similar to Laurel. Not quite the closeness in proximity of two other musicians at the time. But it did… It was all people that same way Laurel Canyon did.

Your album Bidin’ My Time had old friends from all the old places. It was produced by Tom Petty and featured David Crosby and Roger McGuinn. What is the difference between living within a half hour of them and later on. How were those sessions?

Roger lived in Florida, so unfortunately, we couldn’t get him into the studio on the Petty sessions. We sent him the files and he over dubbed at his house. His own little studio he has. David came down and sang. That was nice.

We still have great love for each other. There are only three of us left, and no there will never be a Byrds reunion per se. We all get along quite well. We’re getting older. I talk to Roger every week. Every Friday we get together and talk and we play Trivial Pursuits on Skype. Roger and his wife and two other couples in Florida, and then my wife and I out here. It’s quite interesting. We had a great time. That’s what you do when you get older and you’re not as active in the music business as you used to be. We are actually. Roger works a lot when he wants to. I do when I want to too. Of course none of us are working right now. We’re sequestered. We’re under lock and key.

Did you have any idea “So You Want to Be a Rock and Roll Star” would become an anthem?

No, I didn’t. I think that’s one of the better tracks we’ve ever done. I know I wrote half of it. It’s just that’s where the band got really good. It’s so interesting when I hear that track. I go, “really we nailed it that day.” Mike was playing great on the drums and [was doing] Hugh Masekela. I had worked a couple of days for Hugh Masekela playing bass on some songs he was cutting for this South African Jazz singer Letta Mbulu, who is very good. She sounded like Peggy Lee. They were all Jazz players from South Africa. Crosby and I were on a date. He called us in to play. So I played bass, David played rhythm guitar. I had such a good time. That’s what really propelled me. It also got me to writing songs.

The whole premise of “Rock and Roll Star,” the groove of it and everything, came from working with Hugh. That was all from Hugh. Later on, when we recorded our next album, I had Hotep Cecil Barnard, one of Hugh’s band players come in and play on a song, “Have You Seen Her Face.” Wonderful man from Johannesburg.

I loved that, at the end of part one where they say, so you want to be a rock and roll star. It was so funny the way we wrote that. I started the song in my house in Laurel Canyon. Roger lives across the canyon. I called him up. I say, “Listen, I’ve got something I just started. Can you come over and listen to this?” He says, “Yeah, I’ll come right over.” He comes over, he listens to it. He says, “This is great. Let’s do this for the bridge.” Then we put the bridge to the song, [sings] “And in a week or two if you make the charts…” And I said that’s great. He says, “That’s something Miriam Makeba had done.” He had worked for her as an accompanist. So that song came together quickly. Originally we were like old men at 23 having been around the block a few times, writing this parody of it. So You Want to Be a Rock and Roll Star, we’ll grow your hair long. Do this, do that. It holds up quite well.

What did you think of Patti Smith’s version?

Loved it. She was the first one to cover it. She did great. Patti did it great. You won’t believe this, but my wife saw this record, CD, a year or two ago. Jeff Bridges had done the songs in his movie that he won an Oscar for. Jeff Bridges made an album, and cut “Rock and Roll Star.” So Connie, my wife, brings it home. She said, “You know Jeff Bridges cut this song. I listened to it, and it was really good.” I call up Crosby. He says, “Yeah, email Bridges.” I knew him, but I didn’t know him. I said, “I just got to tell you, you did this fantastic version of ‘Rock and Roll Star.’ At the end you did this whole different arrangement. It’s sort of a breakdown. You guys are all singing.”

He wrote me back in three minutes. He was so excited that I noticed him doing it. I said, well, you did a great job on it. Yeah, a lot of people have cut it. It’s always an honor when someone covers one of your songs. I think that’s the stamp of approval for the writer when someone covers one of your tunes.

The Flying Burrito Brothers covered Merle Haggard. And you and Herb Peterson did an entire album in ’96. Tell me about the Bakersfield sound and Buck Owens, and that whole sound.

The thing that I loved about Buck especially, Buck was a lot like when I first heard Bluegrass. It was so energetic and improvisational in that sense, with so much energy. I love the singing. The Buckaroos were so exciting. Buck said, “I wrote music so people could dance.” As they come in on the weekends, the Blackboard or whatever the place was he played up in Bakersfield. They wanted to dance. That’s the kind of stuff he’d do, these fast shuffles so they could dance. Then you add Haggard, who was a little different. And Winn Stewart and all this. We loved all that music. It was very close to the Bluegrass that Herb and I grew up with.

I remember being turned on to Buck Owens when I was in high school. This gentleman that took me under his wing was the school custodian. He was a country singer, worked on the weekends. He took me under his wing and showed me stuff you won’t believe. My first mentor, I wrote extensively about him in my Memoir that’s coming out.

Yeah, I’ll tell you about Bakersfield Bound. Tony, that cost eight grand. That’s called being prepared and going into the studio and recording it live. It was one of the best records we’ve ever done, I thought. We nailed it. It was really a tribute to all those guys up there.

If you hadn’t gone to Nashville, how might have Sweetheart of the Rodeo sounded?

I don’t know? I’m sure we could have nailed it. A lot of people don’t know we were doing country stuff way before Sweetheart of the Rodeo. On our second album, we did “Satisfied Mind.” It was a hit for Porter Wagoner, a huge hit. And it had a great lyric to it. Then, we consistently did that throughout the rest of the records we made up. Younger Than Yesterday was when I started writing. I started writing a lot of country stuff. Had Clarence White come in and play. He was an old friend of mine from my Bluegrass days. He came and played electric guitar on a few cuts.

Notorious Byrd Brothers was the next album. We did the country stuff on that. Then, we did Sweetheart. So yes, we could have done Sweetheart in LA, the whole album. We did some of it in LA. We did most of it in Nashville, then we came out to LA and finished it out here. We could have done the whole thing out here. I think Gram Parsons was being ever so ambitious at the time. He was great. He was ambitious. He was hungry. He really wanted to push for that. We said, okay, let’s go to Nashville. Columbia Records was a champ. They didn’t object. They didn’t say, “Why are you doing this? You’re supposed to stay within the parameters of your sound.” Well, we did. The Byrds never went to make Sweetheart the Rodeo to be a crossover band. Now we’re a country band. We weren’t a country band. We were The Byrds doing a country album. That’s what it was all about. It always was.

What did that do? It opened huge flood gates. What came next? In order, chronologically Flying Burrito came. What comes after that? Poco on through to the Eagles. Originally, the Eagles, as a four piece, were doing more country stuff before they hired Joe Walsh. The Sweetheart of the Rodeo was not the biggest selling record at the time. It was getting panned in the press because – “What are The Byrds doing? What’s going on here?” Now, then later, in about four or five years, it started to really pick up steam. Then, the day I saw it as one of the top 50 or top 100 albums in Rolling Stone, I was going “What?” It wasn’t my favorite record. But it was a good record. It was a good experiment. We had a great time. We weren’t going to continue as a Nashville band. There you have it in a nutshell.

When you first joined The Byrds, you were a guitarist, and you switched to bass. Who were you listening to on the bass when you were making this?

That’s a good question. Actually I went from mandolin to bass, which is really weird. So when I first started playing, I bluffed my way into the job. I told him I could play. Roger was such a great musician, the best player out of all of us at the time. We caught up to him. I would listen to McCartney obviously. I said, well, he plays with a pick. Interesting. When The Who came out, I loved John Entwistle. He was a fantastic bass player. Those two guys I was listening to. Then, I realized that a lot of the session bass players in LA use the pick. It was a sound, it was a certain sound. A crisper sound. Carol Kaye played bass on so many records. The Beach Boys, everybody, she was in the wrecking crew. She used the pick. I decided I was going to learn to play the bass with a pick, which I did. I already was using a flat pick on the mandolin and on the guitar. So it was an interesting change. I weirdly approached the bass as if I was playing bluegrass guitar. I was putting runs in like I would do in a bluegrass band. Then I realized and grew a little more, and I finally figured that instrument out about a year after I started it. Then, I got to play a little bit recently on the tour with Marty Stuart and Roger. I would play the bass in a few The Byrds songs we did. I loved it. Otherwise, it sits in the closet, cobwebs. I don’t play anymore.

But you still write?

My memoir is coming out in September on DNG. They’re publishing it. It just covers my whole career in music in a very positive, good way.Laurel Canyon part one airs on May 31 and part two airs on June 7 on Epix.