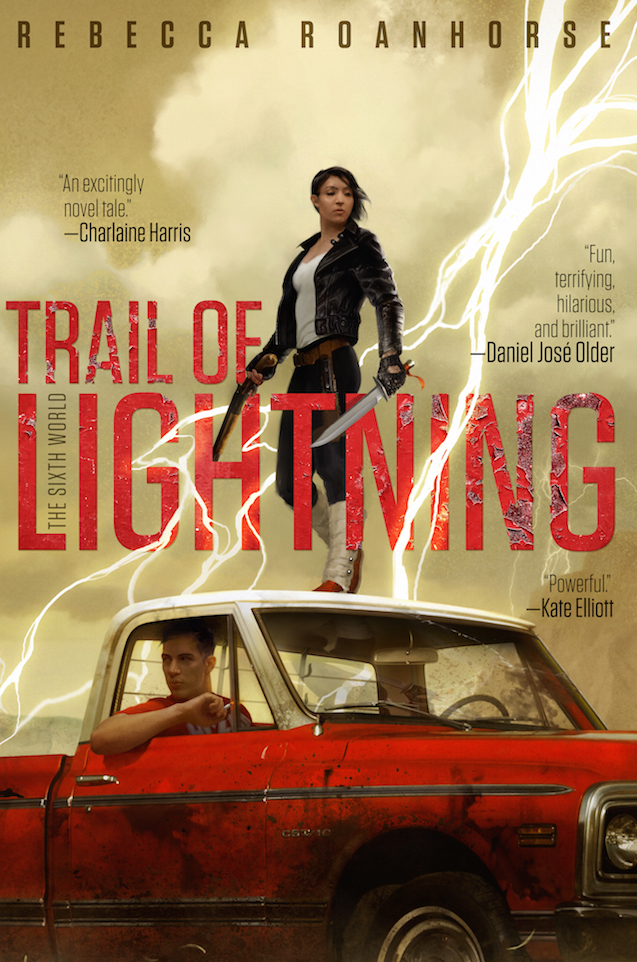

Trail of Lightning: Rebecca Roanhorse Brings Indigenous Futurism to Urban Fantasy

We talked to Trail of Lightning author Rebecca Roanhorse about bringing Native experiences into a speculative fiction world.

Monsters and magic are on the loose in Trail of Lightning, Rebecca Roanhorse’s urban fantasy novel that features Indigenous heroes and fights back against stereotypes along with the monsters. The first in a four-book series, Trail of Lightning introduces Maggie Hoskie, a struggling monster-hunter tasked with saving a community from which she isolates herself.

We spoke to Roanhorse about high-octane fight scenes, the challenges and importance of writing a hero who doesn’t believe in herself, and bringing Native experiences into a science fiction world.

Den of Geek: Trail of Lightning follows monster hunter Maggie Hoskie through a post-apocalyptic world steeped in Navajo legend. What does it mean to you to write fantasy based on Indigenous heritage?

Roanhorse: It means everything. I’m a huge science fiction and fantasy fan; I’ve been reading in the genre my entire life, and I never have seen a story that I thought represented me as an Indigenous woman. I looked around and I didn’t see any stories — particularly in urban fantasy, which is a genre that I really like — where the Native American character was truly centered in their Native culture surrounded by the gods, monsters, and heroes of their culture. I thought, that’s what I wanted to read, so that’s what I decided to write!

I think it’s important and incredibly powerful to offer that kind of representation, not just to Native readers so that they can see themselves in the story but to non-Natives, too, so that they can expand their own imaginations and their own ideas about what Native people and Native culture are like now and into the future.

You mentioned particularly “into the future,” and have talked before about Indigenous Futurism. Is there anything you want to add about making this a science fiction, post-apocalyptic story?

Most Native American stories that you see put us in the past. It’s the 1800s and the Native Americans are dead or dying, and they’re often very limited in scope. They’re often Plains Indians, and they’re wearing buckskins, they’re riding horses, that sort of thing. Even now, in the two movies coming out (they’re not genre movies, but I’m thinking of Hostiles and Woman Walks Ahead) they’re all set in the 1800s. So we don’t seem to get a lot of play or a lot of interest from science fiction and fantasy period, much less putting us in the future.

So it was really important to me to show that Native Americans are still here, and that we will continue to be here, and that our stories can be sovereign. They can tell stories that have to do with our culture and our mythos, and they can be entertaining and exciting and adventurous. They don’t have to always be depressing death marches or stories of alcoholism and trauma. Although my story does deal with a lot of trauma! But hopefully it’s still a fun monster-hunting adventure.

Is there any particular element of Native experience, either lived or mythological, that you found especially important or especially exciting to include?

I wanted to get the food right! I thought it was really important. There’s not a ton of food in the book, but when they do eat it’s important, as is who makes the food and what kind of food they’re eating and where they’re eating it. All of these are details of the Native experience. In the book, Maggie, who is not domestically inclined, makes food for somebody, so it’s kind of a big deal. And also that she makes it for Coyote and Kai is kind of a big deal. She makes bread. And that fry bread she makes is a traditional staple in Native American culture.

It came from nothing; it came from the equivalent of being on rations. It’s the basic ingredient. So they took something that was basically starvation rations, and made something delicious. For me, that’s a great metaphor for Native American culture in general, particularly post-1492. We took the things that were meant to kill us and we made them nourishment. We make them strength.

Trail of Lightning has been described as a Mad Max-like action story. How did you approach writing fight scenes and keeping tension going?

I read a lot of other fight scenes. Actually for this book I went in and picked some of my favorite fight scenes from other authors and dissected them, line by line. I asked ‘what did they do here, what happened next, who talks next, who turns next?’ I literally took them apart to see how they did it.

With that in mind I went back to my own stories and applied my own style, which for this book at least, is really short and clipped and to-the-point. Maggie is not going to write a very pretty sentence necessarily. There’s not a lot of flourish. It’s more of a bare-knuckle boxing aesthetic than a rapier fight on cobblestones sort of thing. So I was trying to bring that into the writing in general, but specifically the fight scenes.

I wanted to make them as visceral and immediate as I could. Writing in first person present really helps put the reader right into the scenes. Quite frankly, I tried not to sugarcoat anything. If there was going to be blood or guts or something gory, I wanted to try to touch on that too. Violence is important in this story. I didn’t want to make it any softer than it was, because a lot of Maggie’s character centers around her violence and the reasons she’s so violent and her discomfort with her own violence. She’s worried about whether that makes her a monster herself.

Talk a little bit about Maggie and how she will grow and change throughout the book.

She’s the monster-hunter, the main character in the story. When you meet her she’s been in isolation. She’s just gotten dumped, basically, by her mentor, who she was also in love with. She had a very complicated relationship with him. It’s a hot mess! So she’s trying to figure out her next step in who she is. She’s very isolated in a community where connection is everything. She’s unliked, and that’s fair, because I don’t think she likes herself very much at the beginning of the story.

She has to learn how to talk to people, generally!

Part of what I liked about her was that her strength came from violence but she was also very nervous and unsettled by herself. That gave her a lot of texture.

That’s on purpose, that her greatest strength is also her greatest horror. I really wanted to play with the question “Can anything good come from trauma or suffering?” Of course, the characters don’t agree. Kai thinks the powers they get through trauma are a blessing, and Maggie thinks they’re a curse. I try not to really answer that question, because I don’t know what the answer is. But I’m interested in the question.

When I wrote Maggie, I wanted her to stay violent. I’ve had some people ask why she hasn’t come full circle or why she hasn’t realized the things she has done are wrong. And I think that’s realistic. I’m not sure people do that. Particularly I’m not sure Maggie would do that, because I’m not sure she has enough self-awareness to do that. I think she has a much longer journey. She isn’t recovering so much from the trauma in the book as she is beginning to acknowledge it.

People have relapses. She can want for all the world not to kill people any more, but I’m not sure that’s going to work out.

And it is a four book series. Things will change, and she’ll have other challenges and emotional issues to face … I didn’t want that question very neatly answered, because I don’t think Maggie is a neat character. She’s messy. And sometimes you have to be selfish to survive. So her thoughts might feel selfish in the end, but often that’s what women have to do. Often that’s what women of color have to do if they want to survive. If you’re not for you, you’re going to have a hell of a time.

Her partner Kai is described as an “unconventional medicine man.” You’ve said in previous interviews that you wanted to place him in a very modern context. Where is he in life at the beginning of his book and what is the core of his character?

It’s twofold. I wanted to create a medicine man character, because that seemed important. But I didn’t want to fall into any of the stereotypes or conventions of what non-Natives think of when they think of medicine men. Because I know medicine men. And I know medicine men in training. Very traditional guys who are just like Kai: they’re young, they want to go to the club! They’re modern, contemporary people. But they have also this traditional side that leads them to want to train to be medicine men.

Medicine men are the healers in the community. The way that non-Natives might go to a doctor or a psychiatrist, Natives will often go to a medicine man. Often they do both. So I knew I wanted that. I knew I wanted him to be young and sort of attractive, but to have layers too. I wanted him to have secrets and his own life outside of when he meets Maggie. We’ll get more into Kai particularly in book three, when we go back to Burque, where he’s from.

I think he’s complicated in his own way. He does function as a foil to Maggie. He’s the healer, she’s the killer. He’s optimistic, she’s pessimistic. And a lot of the reason I chose to do that has to do with Navajo philosophy. Navajo philosophy is about balance, so often if there’s something wrong with you it’s because you’re out of balance. You have to bring balance back into your life somehow.

Maggie is entirely out of balance, and so Kai provides that balance for her.

What did you find most challenging about writing Trail of Lightning?

Getting the representation right was very important. I’m not Navajo; I’m Ohkay Owingeh, a tribe in northern New Mexico. I’ve lived on the Navajo reservation and I’m married to a Navajo man, but it’s not my culture.

I wanted to be very careful about the stories I chose to use, the way that I portrayed people and places and everything that went into the world-building I tried to be very conscious that this was going to be a lot of people’s first introduction to Navajo culture, and that I’d have a lot of Navajo readers. I didn’t want to let them down. I didn’t want to get it wrong.

I wanted to create somewhere where they could see themselves in genre fiction, because that would have meant the world to me as a kid. Even as an adult it’s very exciting! You’re like like, if it’s in a book it must be important, it must be real. You’re telling my story.

What are you reading currently?

Witchmark by C.L. Polk. That’s sort of the opposite of my book. It’s set in an Edwardian England-style fantasy world. It’s very proper and restrained. But it also has a murder mystery at the center of it, and witches, and interesting angel-fae type characters. I’m really digging that.

What are some books by Native authors you would recommend?

If you’re interested in a different vision of a post-apocalyptic world written by an Indigenous writer, people should check out Cherie Dimaline. She wrote a book called The Marrow Thieves. She is First Nations, which means she’s Canadian. Hers is a YA, but it’s definitely readable by anybody. Her post-apocalyptic vision is much darker I think than mine, in the sense that in my version everyone on the Navajo reservation is doing pretty ok, except for the monsters.

In her version, non-Natives have stopped dreaming. And they’re all going insane and dying because of it. The only people who can dream any more are the Native population. So these government goon squads hunt down Natives for the marrow in their bones to make a serum that’s supposed to help you dream again. Her protagonist is a young boy on the run with a ragtag group of other Indigenous people. It’s great. It’s really well written. It’s very creepy. It touches on very contemporary issues about resource exploitation and Natives being forced into boarding schools. But it comes at it through a lens of science fiction.

You’re working on other books in the Sixth World series, as well as a children’s book, Race to the Sun, from Rick Riordan’s imprint. Anything in particular you want to add about these or other upcoming publications?

The second book in the Sixth World series is called Storm of Locusts, and that will be out in April 2019. In Trail of Lightning we stay within the walls of the Navajo reservation, of Dinétah. But in Storm of Locusts we’re going on a road trip. My shorthand for Storm of Locusts is it’s a girl gang road trip down post-apocalyptic Route 66. You’ll run into all sorts of things like newborn casino gods and a cult leader with a penchant for locusts and all sorts of interesting things along the road. Maggie has to go save Kai from himself.

In 2020 I have an epic fantasy coming from Saga press, and that is an Anasazi-inspired epic fantasy, so I’m excited to try my hand at that. That’s going to be larger in scope. You’ll have these great matriarchal clan-dwelling families. It has intrigue and celestial prophecies and dark rebellion. All the things people like about epic fantasy, but in an Anasazi world.

Trail of Lightning by Rebecca Roanhorse is now available to purchase (and read!) via Amazon, Simon & Schuster, or your local independent bookstore.