Speculative Fiction Series with Fantastic Conclusions

Looking for a not-too-long speculative fiction series that sticks the landing? We suggest one of these three...

In the land of fantasy novels, it’s not uncommon for series to go on for seven, twelve, or fifteen books. Some of my favorite series have clocked in at ten books or more. George R. R. Martin’s “Song of Ice and Fire” books are planned to hit seven in order to catch up to where the television adaptation Game of Thrones ended; the “Wheel of Time” books by Robert Jordan, completed by Brandon Sanderson, reached an epic fourteen; and books sixteen and seventeen of Jim Butcher’s “Dresden Files” are due out this year.

When such length is the norm, it become even more impressive when authors can pack a solid punch with a trilogy. This year, three solid trilogies have already concluded, giving readers a chance to see how even a short series can really stick the landing when it comes to that final installment. Kameron Hurley’s Worldbreaker Saga concluded in The Broken Heavens, wrapping a six-year, multiverse spanning epic in around 1500 pages. Jennifer Estep’s Crush the King brought the story of gladiator queen Everleigh Blair to a satisfying close after setting her against the neighboring tyrant set on killing her. And in Cyber Shogun Revolution, Peter Tieryas brought the political arc begun in United States of Japan to an end—a point that may well be a launching point for future installments. All three of these series are absolutely worth picking up and delving into.

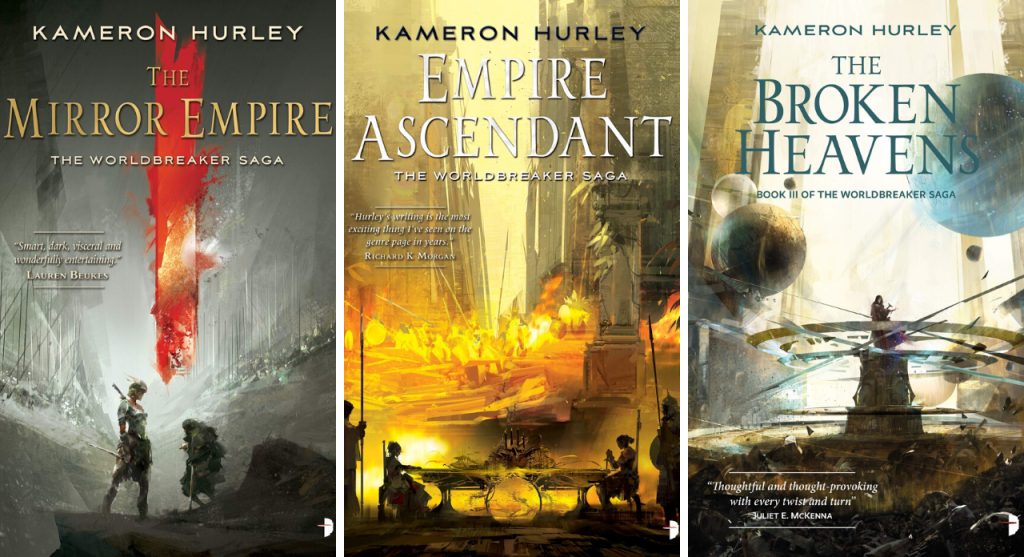

Worldbreaker Saga

I’d been meaning to pick up Kameron Hurley’s work since her essay “We Have Always Fought” won a Hugo. The publication of The Broken Heavens was the incentive I needed to finally approach her work. The Worldbreaker Saga is not for the faint of heart, and the sheer complexity of the worldbuilding means this is no brain-candy—but that requirement for readers to pay attention and truly engage with the work makes the experience of the series so much deeper.

The Mirror Empire begins with the story of Lilia, daughter of a blood witch, who is thrust from her world into a mirror version, Raisa, where rebels against the warrior ruler of their people plan for a better future. But there’s a cost, and it’s a long time before Lilia discovers just how much blood must be paid to create a new world. In the intervening time, Lilia’s friend Roh longs for adventure and freedom—but instead finds danger and slavery. The newly anointed Kai, Ahkio, strives to keep the peace in his nation, the Dhai, even as enemies threaten to unravel the very thing that makes the Dhai who they are. Zezili, a general of another nation’s army, is sent on a mission of mass slaughter she is certain will devastate her nation—and she comes to the conclusion that she must stop her own empress’s plan. Taigan, a gender-changing sanisi—an assassin who can use powers drawn from the satellites—seeks others who can draw on the dark star, Oma, in order to stave off apocalypse.

If that sounds like there’s a lot going on, it’s because there is—and that’s before Hurley reveals that the reason Zezili must slaughter people of Dhai descent, and the reason Ahkio’s mysterious enemies look like his own people, is because that worlds are colliding, and people from multiple worlds are trying to enter Raisa, but to do so, their double must be dead. As the series progresses through Empire Ascendant and into The Broken Heavens, the number of versions readers experience of each character grows. Kirana, Ahkio’s sister who dies at the beginning of The Mirror Empire, is also the empress bent on conquering Raisa so her own people can escape their dying world. Other versions of Lilia have already perished trying to save the world.

There are so many pieces in motion that it’s a true accomplishment how Hurley dovetails them together in The Broken Heavens. The worldbuilding at work is vast, not only because it spans worlds that mirror each other, but because Hurley designs so many unique cultures, all of which have their own understanding of gender and gender roles, as well as different religions and different understandings of the satellites that grant some people magic. (The magic itself, thankfully, works consistently across the world.) Despite starting from the initial viewpoint of Lilia, which predisposes the audience to identify with her, Hurley also gives such attention to developing the antagonist, Kirana, and giving her such pure motives despite her heinous tactics, that readers may be torn in who they’re rooting for by the end.

And after one false climax, the true ending of the trilogy falls exactly as it should, as if it were the only inevitable result of the story from the beginning. Yet at the same time, it feels so fragile and hard-won. To tread that balance, and to create characters so deeply empathetic while also utterly monstrous, shows supreme skill, and it won’t surprise me at all if Hurley returns to the Hugo ballot next year for best novel and for series with this triumphant conclusion.

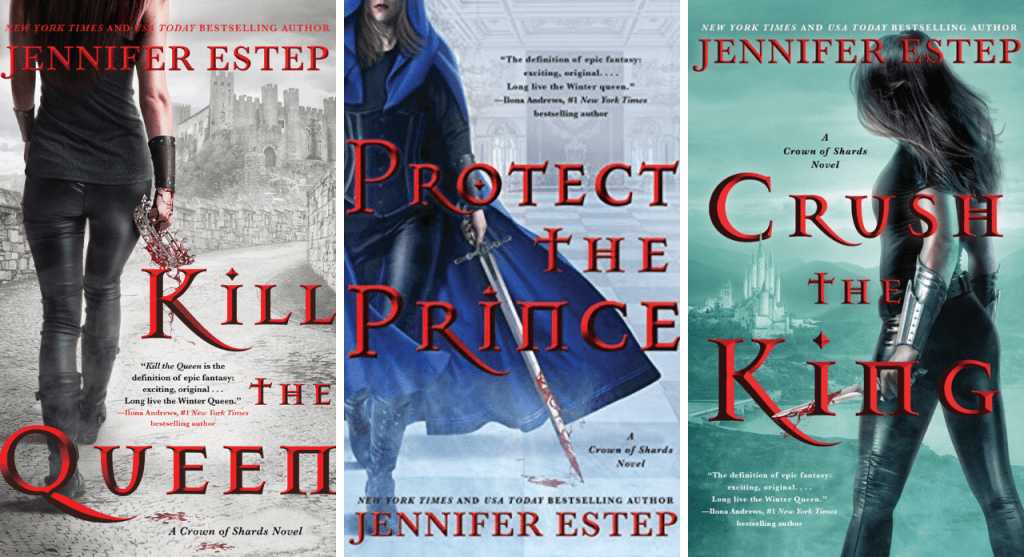

Crown of Shards

Jennifer Estep is no stranger to lengthy series. She has eighteen books in her “Elemental Assassin” urban fantasy series. But she’s also created a solid trilogy that not only introduces an incredibly cool world, but brings her protagonist’s story through a full, complete arc. Unlike Hurley’s trilogy, I’ve been following the “Crown of Shards” books since the first came out in 2018 (covered here), and the second novel was one of my picks for best of 2019 here at Den of Geek.

The series begins when Evie, a royal from the wrong side of the royal family, is one of the only survivors of a massacre that kills the entire Blair family. Her cousin takes the throne, and Evie goes into hiding with a gladiator troupe. Suddenly, Evie is thrust into a life of combat, and she trains hard to become good at it, learning how to utilize her skills in dancing and courtly subterfuge as an asset in battle. She gains the trust and friendship of the troupe members, as well as developing an unrequited romance with Sullivan, a bastard prince from a neighboring kingdom. Unsurprisingly given the title of the first volume, Evie must Kill the Queen in order to save her own life—and restore peace to her kingdom.

The second novel, Protect the Prince, focuses more on Evie’s attempts to wrangle her nobility under control while fending off attacks from the Mortan king, who plotted the original massacre, and forging alliances with other nations. Although the intrigue and political maneuvering drive the plot, the thread of romance between Evie and Sullivan remains a strong aspect of the story. As the finale of that novel shifts their relationship, it’s a delight to see how the pair come together as a team in the final installment. Some novels need that romantic tension in order to keep the stakes high; Estep deftly moves from unrequited to passion in a way that bolsters the plot rather than taking away from it. Which is important, because the plot follows the long game Evie began in the first novel—and the threads that Estep carefully began weaving—to its ultimate conclusion.

No longer hiding behind deniable assassins, the King of Morta and Evie come face to face. Although the context is one of supposed peace—an Olympics-like tournament where the best of each nation compete—it’s clear from the very first encounter that Evie and the Mortan king would like nothing more than to murder each other. Estep alternates intense courtly intrigue—never has a card game had such high stakes!—with assassination attempts and explosions of magic, revealing just how much Evie has grown into her role as the Winter Queen, and how willing she is to risk everything to save the people—and nation—that she loves.

While the trilogy absolutely brings the story to a close, it’s nice that Estep has left the door open for more stories in this world. Some of the side characters (one who barely appears in this book) have given hints about their own narratives, and because the world of magiers, masters, morphs, and mutts is just so darn cool, I’ll be happy to come back for any story Estep wants to write.

United States of Japan

Peter Tieryas’s novels set in the United States of Japan aren’t the same style of formal trilogy featured in either Hurley or Estep’s work. Instead, each of the novels is a stand-alone in the same alternate world where Japan and Germany won World War II and divided the United States between them. United States of Japan, published in 2016 through a different publisher than the following two novels, primarily takes place in 1988. It focuses on the characters of Captain Beniko Ishimura, a government censor who never gets the promotion he deserves, and Akiko Tsukino, a member of the Tokko, the thought police. Together, they track a rogue officer and programmer who may be behind a seditious game. Throughout the story, Akiko has to increasingly acknowledge her own doubts about the Empire that she serves by controlling and monitoring the thoughts of others.

In a moment that captures the themes of all three novels, Ben asks Akiko, “Remember what you said about justice? About making things better? … Do you still mean it?” “I never wavered,” she responds. While the characters and the years—Mecha Samurai Empire takes place in the 1990s, and Cyber Shogun Revolution happens in 2019 and 2020—the core, that search for justice and for trying to make things better, holds firm. In Mecha Samurai Empire, reviewed here and named on Den of Geek’s best of 2018 list, the question revolves around what the military owes its soldiers, and what it means to be a solider. Told in first person, the novel follows would-be mecha pilot Mac through his initial failures to become a pilot and his eventual success as a war hero, which only leads him to question whether he’s meant to be a soldier after all.

In Cyber Shogun Revolution, a title that becomes clear only in the finale, terrorists call into question the responsibilities civilians have for the actions of their military and government. “In every empire, every citizen is responsible for the actions of their military,” the terrorist known as Bloody Mary declares. “Even if they ignore what goes on, do you think you can reap the rewards of what your soldiers do, but not suffer the consequences?” Like United States of Japan, Cyber Shogun Revolution follows a military captain and a Tokko agent; here, Captain Reiko Morikawa is a mecha pilot who was involved in a plot against a traitorous governor, and Tokko agent Bishop Wakana is investigating a German-American scientist performing inhumane experiments. Together, they go after Bloody Mary, who’s threatening the stability of the new governor that Reiko helped put into office. But is the new governor really any less a traitor than the man he replaced? Who benefits from power? Those big questions loom over the novel, and the ideas of right and wrong are consistently murky. If the story were told from the point of view of different characters, who would be the hero, and who would be the villain?

All of these huge philosophical issues and the heart-rending decisions made because of them are set against a backdrop of incredibly awesome technology, including completely immersive cyber bubbles and mecha that defend the city. The novels are all jam packed with giant robot action, and while it’s the ethical questions that stick with me, there’s a tremendous amount of fun in reading about mecha going after each other with plasma swords and chain saws. (A recurring character, Kujira, a wise-ass genius of a mecha pilot who is constantly eating while piloting, is a delight to see again in this third novel.)

While Cyber Shogun Revolution may not be the final book set in this world, it does bring some of the ideas and character arcs introduced in the first book. It takes one character’s arc to a completely different place, and might even bring the history of a nation to a close. And while those thematic questions are consistent throughout, Tieryas never entirely answers them—which seems intentional. Leaving those questions open-ended begs the readers to wonder what they will do when they witness injustice. What will they accept in order to reap the benefits their society offers? It leaves readers with the choice of whether or not they, like Tieryas’s characters, will strive to make things better. Ending the series on that note, and with hope that the future has the possibility to be a better one, is one heck of a way to stick the landing—and Tieryas does it with style.