The Early History of the Batman TV Series

The original Batman TV series starring Adam West is a classic for many reasons.

An instantly recognizable theme song, outrageous death traps, ingenious gadgets, an army of dastardly villains and femme fatales, and a pop-culture phenomenon unmatched for generations. James Bond, right? Wrong. 1966’s Batman television series practically defined the comic book adaptation for the next three decades with its distinctive visual flair and parade of celebrity guests, even as it walked the line between loving adaptation and straight-up parody.

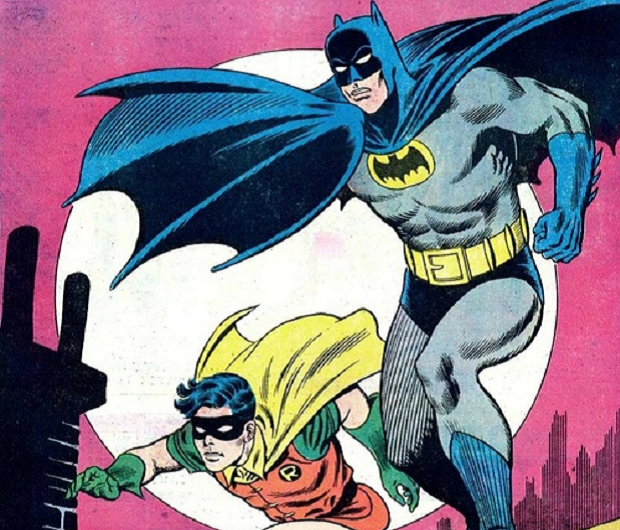

When it first premiered in 1966, Batman was the most faithful adaptation of a bona fide comic book superhero ever seen on the screen. It was a nearly perfect blend of the Saturday matinee movie serials (where most comic book characters had their first Hollywood break) and the comics of its time. But the TV series, particularly during its genesis, was both a product of its own time, and that of an earlier era.

Both Flash Gordon and Dick Tracy had made the leap to the big screen before Superman had even hit newsstands, and both saw their serial adventures get two sequels. While Flash Gordon, particularly the first one, was a faithful (within the limitations of its budget) translation of the Alex Raymond comic strips, Dick Tracy was less so. The famed detective became a G-Man, and there was little in the way of fantastic gadgetry or the unfortunately deformed members of his comics strip rogues’ gallery.

The first proper live-action superhero adaptation, however, was 1941’s The Adventures of Captain Marvel, perhaps the finest serial ever made. Years before Richard Donner and Christopher Reeve, this one made audiences believe a man could fly, and featured a perfectly cast Tom Tyler in the title role, but was still rather beholden to serial storytelling conventions and the aforementioned budgetary limitations.

It took Batman a little longer to make it to the screen, and neither Columbia’s Batman (1943) or Batman & Robin (1949) are particularly distinguished efforts, even by the generally low standards of the adventure serial. Batman’s signature rogues’ gallery is nowhere to be found, replaced with a generic, hooded serial villain, The Wizard, in 1949’s Batman & Robin, or, worse, a distasteful racist stereotype in the form of Dr. Daka in 1943’s Batman, which often comes across as little more than an exercise in wartime propaganda. Batman and Robin are portrayed much as they are in the comics, despite some unfortunately cheap costumes, and less than physically convincing actors in the title roles.

The Columbia serials, with their lousy special effects and hack dialogue, did have one thing going for them: a series of remarkable action sequences. Nearly every episode of each of these fifteen chapter serials featured Batman and Robin crashing through windows, lurking on rooftops, walking tightropes, and engaging in protracted stunt fights with a series of anonymous henchmen. Those sometimes clumsy, but never boring, action scenes from the serials would be repeated and foregrounded (with some notable visual and sonic additions) once the television series came around. What’s more, legend has it that one of the early factors in Batman’s journey to the small screen was the presence of an ABC exec at a party thrown by none other than Playboy‘s Hugh Hefner, where the old serials were screened, and the audience was encouraged to cheer the heroes and boo the villains.

For the most part, the comic book superhero had to adapt to the limitations of the serial format, rather than the medium adapting to the possibilities offered to it by the superhero, and virtually no attempts were made to call attention to the medium which gave birth to them. Whether it’s for practical purposes like budgetary restrictions (note Batman’s distinct lack of a Batmobile in the Columbia serials), or for the purposes of telling a more coherent story (the storybook whimsy found in the Shazam! comics, for example, would have felt out of place in Republic’s relatively grounded Adventures of Captain Marvel serial), there are usually decisions to be made regarding, at the very least, the visual representation of the character and surrounding world.

That changed on January 12th, 1966 when the first episode of Batman hit the airwaves at 7:30, which was then considered prime-time. Batman wasn’t the first comic book show to hit the small screen in color (The Adventures of Superman starring George Reeves had beaten the Caped Crusader to that particular punch several years earlier when it switched to filming in color from its fourth season on), but was handily the most faithful visual and tonal translation of, not only a comic book character and its surrounding mythology, but of the comic book format itself that had ever been seen.

This was, of course, by design, and the show turned the perceived weaknesses of the comics into strengths. And while the fight sequences, frequent use of cliffhangers, and clipped, “serious” dialogue were certainly call-backs to the serials, the visual style of the show was sourced directly from the Batman comics of 1964 to 1965. This probably had more to do with the lack of easy access to back issues as research material for the writers and producers in 1965 than it did with any conscious decision to adhere to any one vision of the character, though.

Executive producer William Dozier, who by his own admission, “had never read any comic book,” brought several Batman comics to read on a flight from New York to Los Angeles, and “thought they were crazy if they were going to try to put this on television. Then I had just the simple idea of overdoing it, of making it so square and so serious that adults would find it amusing [and] kids would go for…the adventure.”

Perhaps the tone of the series would have been different if Dozier had acquired comics from earlier in the Caped Crusader’s published history, as, by this point in the mid-1960s, the Batman of the comics (and ultimately that of the show) isn’t the “grim avenger of the night” from Detective Comics #27, but instead a fully-deputized defender of the status quo of the era. While there was a lighter tone on display in the Batman comics of the mid-60s, there was also Carmine Infantino’s distinctive art, which brought with it changes to Batman’s costume including the now-iconic yellow oval around the bat-symbol, and the transformation of the Batmobile from a bat-headed sedan into a streamlined, bat-winged hot rod.

But the influence of these contemporary stories on the producers of Batman is so strong that a number of episodes were adapted almost directly from recent comics of the day. For example, the opening two-parter (and the very best hour the series has to offer), “Hi Diddle Riddle/Smack in the Middle,” borrows a number of plot elements from “The Remarkable Ruse of The Riddler” story in 1965’s Batman #171. The show’s overnight success was then reflected in the comics, which attempted to duplicate the show’s outrageous tone and over-the-top storytelling, with an even heavier emphasis on “pop-art” visuals.

Dozier, however, deserves considerable credit for helping make this take on the character work, as he “explained to [Adam] that it had to be played as though we were dropping a bomb on Hiroshima…that he wasn’t going to be Cary Grant, full of charm.” A show about two costumed crime fighters preserving order in a city full of colorful characters would likely have been met with understandable cynicism by the late ‘60s. Batman neatly sidesteps this problem by portraying Batman as a comedic, self-absorbed square, thanks to Adam West’s remarkable portrayal, which as Grant Morrison put it in Supergods, “distilled the quintessence of the serials into a thin-lipped, clipped, and stylized performance that was funny for adults to watch and utterly convincing [and] heroic to children.”

The producers then hedged this gamble by using as many of Batman’s most outrageous foes from the comics as possible, casting bankable stars like Frank Gorshin, Burgess Meredith, Cesar Romero, and Julie Newmar in the roles, and encouraging them to run wild. As a kid, I never understood why my father appeared to be rooting for the villains on this show…

Nearly 25 years before Warren Beatty’s Dick Tracy and its four-color palette burned up the box office, Batman tried its very best to make a direct leap from the page to the screen. Colors are bright and primary. The costumes worn by our heroes (and at least a few of the villains) are form-fitting and appear to serve no practical purpose. They are, instead, purely aesthetic affectations that only highlight the grandiose, exhibitionist manias of Batman’s foes, and the utter ridiculousness of the very concept of a pair of masked vigilantes, one of whom is underage, working hand-in-glove with an incompetent police department and an adoring public!

And while later cinematic representations of Batman at least tried to address the question of what kind of equipment, training, and armor would be necessary for a man to subject his body to physical punishment night in and night out, the producers of Batman took the most direct route possible. The costumes of, not only Batman and Robin, but Gotham’s entire most-wanted list, are lifted directly from the comic page, thin material, gaudy colors and all.

Batman ran for 120 episodes over the course of three seasons, along with one feature film. As the show progressed, the jokes got stale, and the edgy satire of the first season became more children’s show than smart parody. It sputtered out at the end of a generally subpar third season. Still, its influence was profound. For much of the next 30 years (perhaps more), it seemed impossible for a comic book character to make the jump to live-action without being given a comedic, parodic touch.

There were attempts to duplicate Batman‘s success, notably with the Green Hornet TV series that helped launch the career of Bruce Lee. But some other notable failures included; unaired (and rightfully so) Dick Tracy and Wonder Woman pilots, and a Spirit television movie (which, despite its shortcomings, is infinitely more faithful to Eisner’s vision than the recent Frank Miller film). While “comic book movies” and TV shows now reflect the higher aspirations of much of the source material, let’s not forget how Batman took two disposable pieces of children’s culture, and turned them, however briefly, into something more.

Note: many of the quotes in this story come from The Official Batman Batbook by Joel Eisner, a wonderful resource about the TV series.