The life and death of teletext, and what happened next

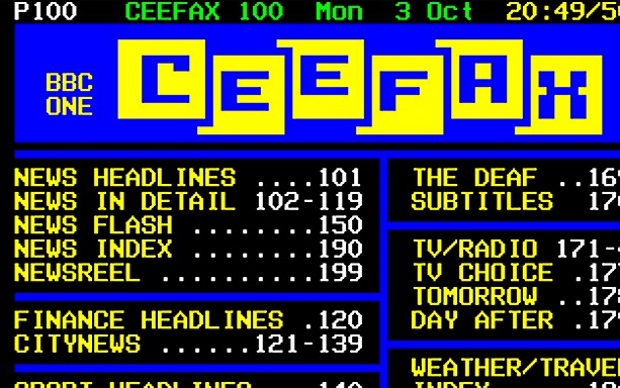

We jump back to Page 100 and explore the legacy of a breakfast institution…

Words That Can Fly

“One page of the Times Newspaper, to be transmitted during shutdown.”

That, so the story goes, was the remit given to BBC engineers in the late 1960s: find a way to transmit a printable page of text so that the corporation’s transmitters weren’t simply left to idle overnight. Their efforts would eventually give rise to an iconic medium that would span five decades, become the basis for a global standard and – perhaps most importantly – let you check the lottery numbers on Sunday morning. (Well, you never knew.)

As is so often the case when a revolutionary technology’s lingering just over the horizon, it’s difficult to know precisely where the tale of teletext truly begins. Engineers at several different corporations were already experimenting with ways of transmitting text remotely, each with different goals in mind. The Post Office, who at that time were responsible for the telephone system, naturally wanted to use their infrastructure to boost the number of phone owners across the country. Boffins back at the BBC, meanwhile, had begun investigating ways to provide subtitled television programmes for the deaf.

The answer arrived courtesy of John Adams, Phillips’ Lead Designer of VDUs, who proposed compressing pages of information into the ‘Vertical Blanking Index’ – effectively the gap between each frame of a TV programme. While the cost of Adams’ solution was a definite concern, the BBC pressed on and unveiled their system, now wittily named Ceefax, to the world.

Not to be outdone, competing companies promptly announced their own endeavours in the form of rival services like ORACLE and Prestel. All were originally incompatible, which would have been a nightmare for TV manufacturers and consumers alike, but a specification was eventually agreed that would later be taken up worldwide. The race to be King of the Teletext Hill had officially begun.

Ceefax was launched formally in 1976. Though take-up was initially somewhat limited since a set-top box was needed to access the service, TV sets with in-built decoders gradually trickled onto the market and the audience swelled. By 1982 over two million TVs – mostly portable ones, as it would take longer for larger sets to catch up – could access both Ceefax and ORACLE, which had launched as ITV’s teletext service and presented itself as a novel new advertising platform.

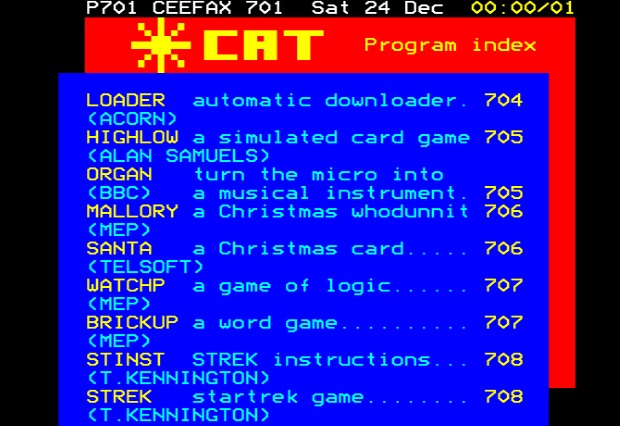

Teletext’s popularity saw the technology used in all sorts of weird and wonderful ways – not least of which was telesoftware, an initiative by the Beeb itself using Acorn’s BBC Micro computer. Enthusiasts could buy an adaptor containing tuning dials and a TV aerial, using it to download utilities and games using the same TV signals that carried teletext. While much of the software is obscure by today’s standards (including a slightly dubious Star Trek game) the service endured into the late 1980s.

Less successful were attempts to update teletext itself. The standard had always been seen as extensible, with older versions simply able to ignore elements they didn’t understand, and broadcasters around the world experimented with enhanced versions of teletext that were able to provider sharper text and more colourful images. With millions of televisions limited to the immensely-popular original standard, however, only a few providers elected to take the upgrade.

Blocky and gaudy as it was, teletext was here to stay.

What, though, did all that mean for us?

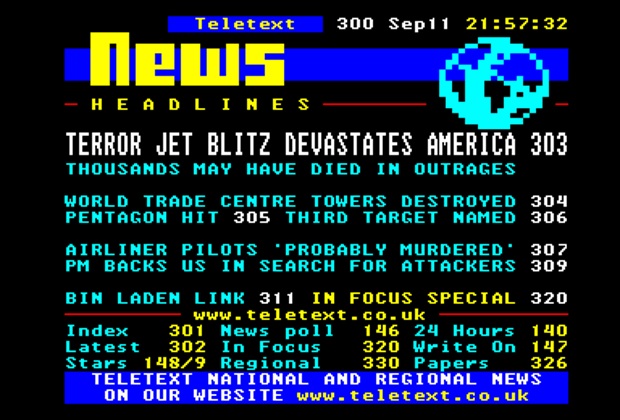

The Worm Turns

As a format, teletext had obvious advantages that kept Ceefax and company alive and kicking well into the 21st century. Being a broadcast system, it was able to update almost immediately with breaking headlines, sports results and financial information – all of which could be vitally important in a world before 24-hour news channels and web feeds. Even better, since a channel’s pages had already been transmitted, it didn’t matter how many millions of users were trying to access that information. During the World Trade Center attacks, many turned to Ceefax for news when overburdened websites collapsed under the strain.

The system was not without its flaws, of course. Not all pages were broadcast simultaneously, so reaching them could be swift or slow depending on how long it took them to cycle back around. Since the whole affair was being carried on the airwaves, it was also possible that a dodgy TV signal could introduce corrupted characters or even scramble a page entirely – a minor inconvenience when reading a news headline, but a frustration when checking information like stocks or timetables.

If you were of a certain age and didn’t care about share prices or discount holidays, there was another problem: teletext was a bit boring. Ceefax in particular, while praiseworthy for managing to achieve a clear and informative voice in a hugely limited space, usually felt like an extension of the evening news. There were a couple of comic strips aimed at the very young and a half-hearted music section to be found here and there, but the various services were sorely lacking in entertainment value.

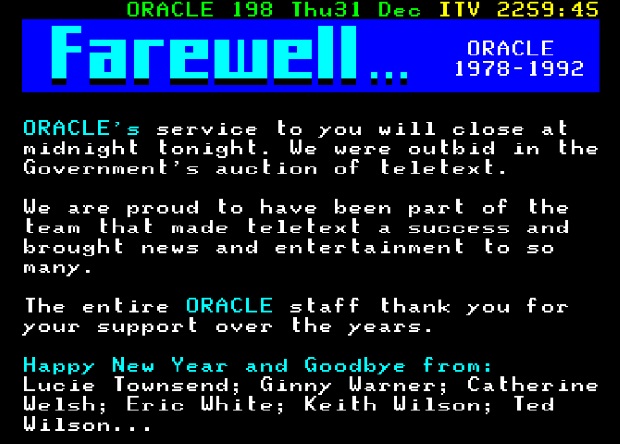

That all changed on New Year’s Day of 1993. ORACLE, who had provided content for their teletext service since its launch, failed to renew their claim to the franchise. Their replacement was the boldly-named Teletext Ltd, and after a rocky start – Oracle had accrued a loyal audience, who were less than impressed by Teletext’s launch day problems – it soon became apparent the new service was more akin to a breezy magazine than a dry informational feed. (Nowhere was this change in tone more apparent than in the adult-oriented “After Hours” section, pages which appeared in the feed only after 11pm and whose ads promised a very different kind of package holiday.)

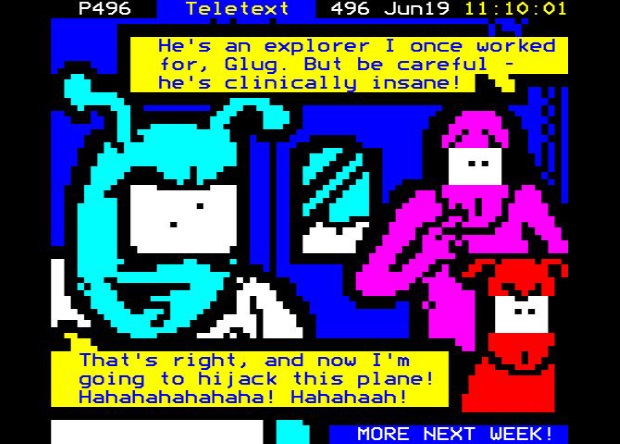

Even better, Teletext had its own video game magazine. Digitiser was daily, it was free, and above all it was funny, thanks to the partnership of Tim “Mr. Hairs” Moore and Paul “Mr. Biffo” Rose – who was also responsible for the service’s surreal comic Turner The Worm. With a need for brevity, and with no game publishers able to pull advertising in response to a bad review, Digitiser quickly garnered a reputation for being unfailingly honest – sometimes brutally so.

Though Digitiser often struggled against internal opposition, it still managed to influence a generation of gamers thanks to satirical mouthpieces like Fat Sow and Insincere Dave providing commentary on the news of the day. It also made heavy use of teletext’s ‘reveal’ feature, a button that could transform entire pages with hidden jokes and characters when pressed.

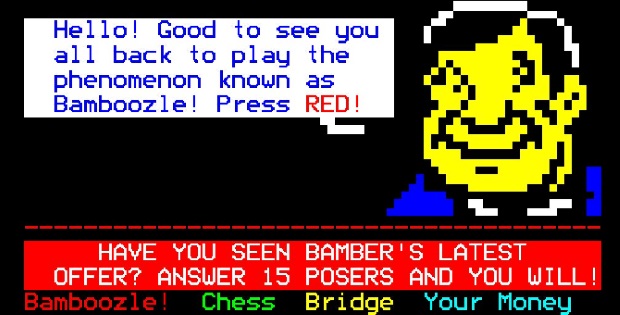

Digitiser wasn’t the only section making good use of its platform. Bamboozle and its sporting spin-off Ten To One were multi-choice quizzes where players used the coloured FastText buttons on their remotes to answer, and they soon became a daily fixture in households up and down the country. Viewers were encouraged to submit their own questions, and the multiple-choice format was occasionally borrowed to host Choose Your Own Adventure-style romps, including several based on adventure show classic Knightmare.

With content that enthusiastically catered to an audience of all ages, Teletext-with-a-capital-T was an out-and-out hit. Little did we know, as we bested Bamber Boozler and waited to make a star turn on Digitiser’s letters page, that the service’s entire existence would one day come under threat…

Rave At Close Of Day

Video may have killed the radio star, but it took a lot longer for digital television to finally sound the death knell of its forebear. Analogue telly lasted until 2012, thanks to a strict government mandate that a full 95% of the country had to be able to make the technological leap, but October of that year saw both Ceefax and Teletext Ltd bid their viewers a fond goodbye as the last of the old transmissions echoed away.

In truth, the popularity of set-top boxes from Sky and Virgin Media, both of which carried their own interactive services and games, had been chipping away at Teletext’s popularity for quite some time. So had the internet and mobile phones, for that matter – strange as it seems, Ceefax and the iPhone 5 coexisted, if only for a month. Like most great innovations, teletext faded quietly into obsolescence rather than being dramatically usurped by The Next Big Thing.

The most popular sections have found ways of adapting to these changing times. Digitiser lives on as Digitiser 2000, a blog (and soon to be TV show) still helmed by Mr. Biffo, while its sedate successor GameCentral eventually merged into the Metro newspaper. Bamboozle, meanwhile, was reborn as an iOS quiz app in 2010, its host Bamber as cheerfully pixelated as ever.

Pleasingly, even teletext’s original editions may not be last as previously thought. Certain video recorders were able to snare that day’s pages along with the programmes they were capturing, which can potentially turn any VHS tapes in your loft into a treasure trove of lost material. You might not be sitting on a treasure-trove of Troughton-era Doctor Who, but those old Rumbelows and Softmints adverts could still be hiding a digital goldmine for those who are actively archiving a unique form of history. (If you’d like to help or learn more, why not reach out to @grim_fandango on Twitter?)

Other tech enthusiasts, fans of teletext as a medium in its own right, have gone even further and found new ways to keep the format alive. Artists who thrive within the restrictions imposed by the original service are still active and frequently take part in exhibitions. Elsewhere, hobbyists previously created tools to mine the BBC’s RSS feeds and present the news as if it were a Ceefax page, and now the truly dedicated can even invest in a Teefax – a repurposed Raspberry Pi that plugs into any teletext TV and continues to provide content.

What is it about teletext that engenders such nostalgia after all these years? Perhaps it’s the nostalgia of charming writing and evocative ideas arising from a simple system, or the sense of taking part in a cultural shift – there we were, summoning our daily dose of information and entertainment of our choosing with the push of a button, all while munching our corn flakes.

Whatever the draw, it’s been nearly half a century since the first ever Ceefax pages, but there’s one truth you don’t need the Reveal button to see: when it comes to keeping the dream alive, the people who are passionate about teletext today remain every bit as creative and ingenious as those who inspired them.