Threads in context, and why it’s still essential viewing

With a remastered version on the way, we look back at what made the 1984 TV drama so horrifying at the time – and still relevant today

First shown by the BBC on 23 September 1984, Threads was must-watch TV. Accompanied by documentary On The Eighth Day and followed by a lengthy discussion on Newsnight, it’s a grim and unflinching depiction of what would happen to Britain if the unthinkable happened – if a political conflict between the US and Russia were to escalate into full-blown nuclear war.

An uncompromising reportage-style drama, Threads was the first film to realistically depict the horrors of a nuclear winter. Shocking, harrowing and hard to watch, it nonetheless made an important contribution to an increasingly urgent debate about the world’s ever-growing nuclear stockpile.

Threads focuses on two families linked by an unplanned pregnancy. Manual worker Jimmy Kemp (Reece Dinsdale) and middle class Ruth Beckett (Karen Meagher) must face the fact that they are having a baby, and that their old way of life will soon be over. Their concerns are those of any new parents: hopes and fears for their child, building a home together, saying goodbye to the Friday night pint at the pub. We also follow local government chief Clive Sutton (Harry Beety) as he struggles to put emergency plans into place amidst the growing likelihood of war. It soon becomes very clear that the city is woefully underprepared for a crisis of any kind, but in that very British way Sutton and his officials carry on regardless – unaware that, in the face of the storm to come, all preparations are ultimately futile.

Framing this drama are news reports about growing political tension around the world. We learn piecemeal, through snippets of television reports and glimpsed newspaper headlines, that in recent months a coup in Iran has been followed by a Soviet occupation.

What follows is a complex sequence of small scale political escalations, events that are alluded to but never fully or coherently explained. By themselves, none of the steps towards conflict seem irreversible, but together they constitute a crisis.

All this occurs firmly in the background of the characters’ lives, and is largely ignored: TV reports are turned over to something more interesting, newspapers are delivered without headlines being read. It’s only as the crisis deepens that people start to pay attention.

I have to confess up front that I am too young to have seen Threads on TV when it was first shown and – like many others my age – I grew up with only a vague notion of what nuclear annihilation meant. (I have a dim memory of seeing Raymond Briggs’ 1986 film When The Wind Blows but as my only clear recollection is thinking it a lot less fun than The Snowman, I was obviously far too young to understand that that was the point.)

In fact, I had not seen Threads until now. It was a name I was familiar with, and I knew it was a tough watch, but nothing more. With news of an imminent Special Edition, I really had no excuse to put off watching it – and besides, the new DVD cover intrigued me (and more importantly, terrified me).

Researching the film’s background for this article did nothing to allay my fears. Something told me that in this case forewarned would not be forearmed, and I approached the film with a vast amount of trepidation.

I was right to be trepidatious. From the very first shot, of a lone car parked ominously close to a cliff edge, it was clear that Something Very Bad Indeed was about to happen.

Cold War renewed

The early 80s were the first time in a generation that full scale nuclear war seemed not only possible but probable.

It’s hard to imagine now, nearly thirty years after its demolition, but in 1984 the Berlin Wall was a very solid and enduring dividing line between two opposing world powers: the countries of NATO, including the US and Britain on one hand, and those united by the Soviet-sponsored Warsaw Pact on the other. Europe was very much at the centre of these international tensions, and those old enough to remember the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis just over twenty years earlier knew that political conflict could escalate quickly and unpredictably.

The 1979 invasion of Afghanistan by the Soviets had soured relations between East and West, and in the early years of the new decade both began to move away from the détente that had held their nuclear ambitions in check since those anxious months in the sixties. In 1980 Ronald Reagan was elected US President. Vociferously anti-communist, he immediately initiated what would become the largest peacetime military build up in American history.

Tension rises

1983 in particular was marked by a series of political crises, each of which moved the world a little closer to war.

In March, Reagan escalated the rhetorical conflict, labelling the Soviets an “evil empire” in a speech to the British House of Commons. In April, US military aircraft strayed into Soviet airspace during a navy exercise in the North Pacific. The USSR threatened retaliation. In September, a Korean Airlines passenger jet was shot down by the Soviets for an airspace incursion over the Sea of Japan – with the loss of all 269 civilians on board. September saw the Soviets’ early warning system malfunction: a retaliatory nuclear attack on the West was only averted by a quick thinking Lieutenant Colonel in the Soviet military. A full-scale NATO military simulation in November was so realistic it convinced the USSR that the Americans were, in fact, covertly preparing for a real war. Across Europe, Soviet nuclear bases were placed on highest alert. It was the closest the world had come to nuclear confrontation since 1962.

First strike mentality

It’s easy to see why the Soviets were so nervous that November. Capable of being launched in minutes, and with a time-to-target of between 4 and 6 minutes, the US’s Pershing II missiles had hard target capability – meaning they could take out weapons silos and command bunkers buried deep below ground.

Both sides knew that a massive and all-encompassing preemptive strike was the only way to win a nuclear war. The stakes were incredibly high. Indecision or delay – of even a few minutes – could mean the difference between survival and total annihilation.

Anxiety at home

Britain, meanwhile, was struggling with crises of her own. The country was suffering a series of upheavals that would cast a shadow over the country for decades to come. Even though the worldwide energy crises of the 70s had eased, in 1980 the UK economy returned to recession. Thatcher’s stringent fiscal policies were busy tearing down the old certainties of strong trade unions and a stable job market. In 1982, unemployment passed 3 million for first time since the Great Depression. Industrial unrest, strikes, Provisional IRA bombings and race riots took hold across the country, with the old industrial heartlands of the North particularly hard hit. For the working men and women of Britain, it seemed as if society was collapsing around their ears.

But Britain’s location at the edge of Europe did not offer any guarantee of safety in the event of nuclear war. After all, Britain was at the heart of NATO’s nuclear commitment. In 1980 the British government announced that, for the first time, US missiles would be stored in – and operated from, if necessary – the UK. There was no public debate.

As the first missiles lumbered through the gates of RAF Greenham Common in November 1983, no-one could predict which way events would turn, at home or abroad. For better or for worse, it looked as if nuclear weapons were here to stay.

People had become used to the jargon that surrounded the debate about a nuclear future – IBMs, kilotons, radiation sickness, fallout – but what did the words really mean? What would a nuclear war actually look like? Few in Britain at the time had any idea. Threads would change all that.

Treading new ground

There had been a couple of similar TV films before Threads, most notably the US drama The Day After. Starring Jason Robards and Steve Guttenberg, 100 million people across America had watched its debut in November 1983. It had a massive impact, stimulating national debate and making the cover of Time magazine.

A British film had also tackled the subject back in the 1960s. The War Game, written, produced and directed by Peter Watkins under the aegis of the BBC’s The Wednesday Play is a black and white reportage-style drama that focuses on the collapse of society following a Soviet nuclear attack.

Scheduled to be broadcast in October 1965, it had been pulled by the BBC (under pressure from the government) as being too realistic – and too horrifying – for the British public to view. After a brief theatrical release (and winning the 1966 Oscar for best documentary feature), it was subsequently shown at private screenings, but had never been seen by the public at large (and was not to be shown on terrestrial television until the BBC’s 1985 After The Bomb season, marking the 40th anniversary of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings, where it was shown alongside a repeat of Threads).

It was a viewing of The War Game that inspired then-Director General of the BBC Alastair Milne to commission Threads. Just as The Day After had done in the US, he wanted to make a film that would revisit the issues raised by The War Game and bring them up to date for a contemporary British audience.

‘Beyond Armageddon’

Since the late 80s, Mick Jackson has enjoyed a successful career directing big budget films in Hollywood (including LA Story, The Bodyguard, Volcano and, most recently, 2016’s Denial) but in the 70s and early 80s, he was creating documentary and drama output for both the BBC and the brand new Channel 4.

In 1982 he was busy producing a new BBC1 science documentary series, QED. One of the first episodes overseen by Jackson was A Guide To Armageddon, an exploration of exactly the issues Milne had in mind for Threads. On its strength, Jackson was hired as director for the new project, which had been given the working title Beyond Armageddon and a generous budget of £350,000.

If the film was going to be a useful contribution to the nuclear debate, it needed to incorporate the latest scientific thinking and research, and an impressive number of physicists, psychologists and other scientists and theoreticians were consulted during production, including Nobel Peace Prize winner Joseph Rotblat and cosmologist Carl Sagan (who had also conducted experimental research on radiation in the 60s).

But Threads was not just about presenting research; if it was to be effective as a drama it needed a suitable story on which to hang the science. Jackson turned to a dramatist known for his naturalistic portrayals of ordinary British life, Barry Hines.

Hines had seen for himself the parlous state of working class communities in Britain. Growing up in South Yorkshire in the 40s and 50s, he’d worked for the National Coal Board and as a teacher before becoming a writer. Best known for his screenplay for Ken Loach’s award-winning 1969 film Kes – Hines also wrote the novel on which it was based – many of his stories deal with social dislocation in the declining industrial North. Hines would bring his passion for social commentary to the script of Threads, setting it in an ordinary Sheffield suburb, not far from where he had grown up.

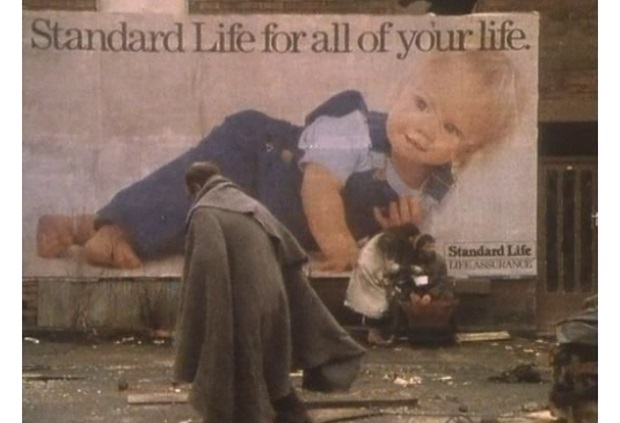

Hopelessness and helplessness pervade the script. The growing nuclear threat becomes just one more pressure on a society already dealing with high unemployment and degradation of local services. Public protest about the two inevitably become conflated: anxiety about a future of nuclear destruction is interwoven with anxiety for a future without jobs. At the root of both is a fear of society’s impending collapse.

Experiencing Threads

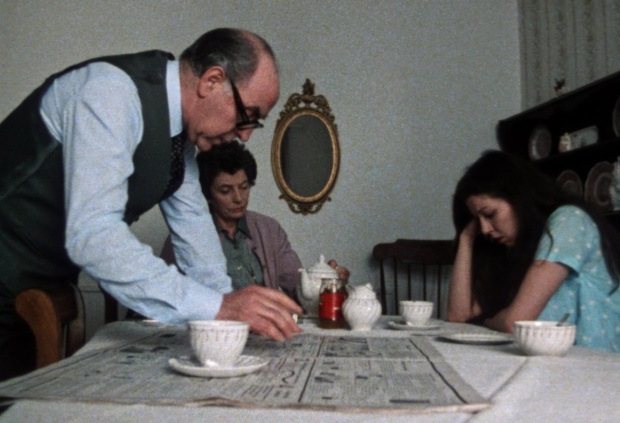

Threads is a masterclass in naturalistic, realistic portraiture. Jimmy, Ruth and their families, Clive Sutton and his wife are all established with a brilliant economy of both time and dialogue. There’s also some wonderful, understated acting from the leads. It’s in the small gestures, the glances and the things left unsaid that we learn most about their characters. The humdrum nature of their world – and the intimacy of the 4:3 aspect ratio – brings their lives into close proximity to ours. Threads doesn’t feel particularly dated; the old cars and the hairstyles don’t distract because the drama is so involving.

Slowly and unremittingly, the tension builds as – in both the domestic and international settings – conflict looms ever closer. (As they plan their new lives together, Jimmy and Ruth’s two very different families meet each other for the first time, and the film finds a quiet comedy in building up this most British of culture-clashes. But when, at length, the two families come face to face at the Beckett’s house, there is no release of tension: the camera holds them at almost at arm’s length, in a long-lensed static shot, for what seems like an age. Framed in the darkness of a stuffy hallway (only middle class houses have halls, after all) they greet each other awkwardly. But then, just as it seems their worst fears of social embarrassment are about to be realised, we cut away to another scene and the denouement never comes.) Throughout the film we are continually led to the edge of confrontation but never allowed the release that experiencing it would provide.

Threads also makes impressive use of a variety of stills, archive footage from other conflicts, and footage that feels archive but is undoubtedly not – it’s hard to tell what is ‘real’ and what’s staged. This broadens the focus of the drama and makes it feel much more rooted in the real world. Most importantly, it allows the film to blur the line between drama and documentary. Matter-of-fact narration and title cards give the film the air of a documentary, as does incorporating elements of the Public Information series, Protect And Survive – practical advice for homeowners that only serves to underline the tragic and faintly ludicrous situation Britain finds itself in as it prepares for an unwinnable war. As his father constructs a Heath Robinson fallout shelter in their kitchen, the smallest Kemp sibling remarks with relish, “it’s like going camping” – a pathetic reminder of a can-do, Boy Scout British optimism that will soon be extinguished.

When the unimaginable does happen, Threads becomes something else again.

Shocking images blend the mundane with the horrifying: milk bottles melting in the firestorm, bodies burning to ash in the rubble. Nothing is left untouched or undefiled by radiation. Life returns to subsistence levels as nuclear winter settles over the UK. Sickness, starvation and death become inescapable. Survivors hoard bits and pieces of broken objects – all that remains of life before the blast – in dirty plastic carrier bags. A scavenged dead rabbit becomes an unimaginable feast.

It’s the visual images that stay with you: a sudden splash of crimson blood against a grey wall when all before was colourless; children laboriously unpicking precious scraps of fabric one strand at a time; the pristine black silhouette of an undamaged marble tomb – as if death is the only thing in the world that has retained its sharp outline.

All this is delivered to us with a coolness, a deadpan detachment that is sickeningly unsettling. As time passes, characters simply disappear from the story – and we are left to imagine what has happened to them. It’s in the most offhand way that we discover the fates of those in the command centre under Town Hall.

The film holds no-one responsible for all this except, perhaps, those at the very top of the chain. It calmly sets out the steps to war, with local officials no more to blame for the chaos than those left dazed and destitute once the firestorm has passed. Ultimately, all preparations to survive are futile, a child’s toy windmill in the path of a hurricane.

Threads today

Threads is an apt title for this powerful and thought-provoking film. As the narrator informs us at the outset, invisible but indissoluble threads bind every part of society together so that if one part falls, it all falls. How much more true that is now than in 1984! Think of all the new technologies that have arisen since then, and how much they are truly interwoven with the fabric of our lives.

But watching the film made me realise that the title also refers to something else: how gossamer-fine life is, and how fragile our existence.

My generation has been lucky to grow up in a time when the shadow of nuclear war has receded and the world has taken a step back from the brink. In 2018, it feels as if those safer times are ending. This is an important film that has become more, not less, relevant since it was first released.

I saw Threads with the lights on, in a room full of other people, in the middle of the day. But it’s still one of the most traumatic things I’ve ever watched. It’s not for the faint-hearted, but it truly is something everyone should watch.