The Sopranos Sessions Review: A 5-Star Tribute to a 5-Star Show

20 years on from The Sopranos' first episode, new book The Sopranos Sessions is a compelling, insightful dive into the show's legacy.

“The show’s gonna be forgotten, like everything.”

This is how David Chase, the creator of The Sopranos, described the legacy of his most famous body of work to Matt Zoller Seitz and Alan Sepinwall during one of the many coffee-house round-tables they convened for The Sopranos Sessions, a weighty tome – filled with recaps, discussions, dissections, analyses, insights, and interviews – being released this week to coincide with the twentieth anniversary of the transmission of the show’s first episode.

Chase’s shoot-from-the-hip, fatalistic world-view is often a dead ringer for that of his most famous fictional creation’s, depressed mob boss Tony Soprano. Tony would almost certainly have assessed his own existence in the same terms as Chase does the show’s. Namely: “It’s all a big nothing.”

And on one level, of course, Chase is entirely correct. There will indeed come a time when even our most celebrated works of art and our most iconic heroes and villains – Einstein, Hitler, Buddha, Mr. Rogers – will inevitably recede and vanish into the infinite mists of existence. That final cut to black awaits every one of us, both individually and as a species.

And yet, ten years after its end, and twenty years since its beginning, The Sopranos still dominates most of the “Best of” lists compiled by the critics who matter; and few viewers with any serious appreciation for television as a dramatic medium would dare place it outside the top three of the greatest series ever made. Its legacy, then, despite Chase’s dark-edged humility, shows no signs of fading.

We’re at a time in pop culture history when we are surrounded with – some might say drowning in – choice. It sometimes feels like there are more TV shows out there than there are people and not enough years in even the most generous estimates of our life cycles to introduce ourselves to more than a minuscule fraction of them. The added problem is that a great deal of today’s TV is good, and much of it is great. We’re drowning, but at least we’re drowning in Dom Perignon. Among other things, The Sopranos Sessions reminds us just how much of this proliferation of prestige television we owe to The Sopranos, and why – even after all of these years – the show still holds an unchallenged position at the head of the TV hierarchy.

The Sopranos was, in essence, an anti-TV series, and Tony Soprano was an anti-hero the likes of which audiences had never seen before, one who would push the boundaries of our empathy and understanding to their limits and beyond. It was a show about the intersections between Family and family; faith and betrayal; guilt and innocence; dreams and reality; good and evil; cunnilingus and psychiatry; and, of course, the sacred and the propane (sic). It was a show about everything. It was a show about nothingness.

Few could’ve realized it at the time, but The Sopranos – cinematic in its scope and vision, literary in its depth and complexity – was about to shake up and remake the TV landscape, ushering in a new era of revolutionary TV characterized by ever greater risks and almost boundless creative freedom.

Further Reading: Best Gangster Movie Food Scenes

Without The Sopranos, without James Gandolfini, without Edie Falco – without that whole, remarkable, almost pitch-perfect cast – without HBO, without that team of writers, directors and producers, and almost definitely without the clarity of vision brought to bear on it all by the bold and uncompromising genius of Chase, TV today might have been a whispering, barren wasteland, filled only with generic cop shows and hoary old hospital dramas. Your eyes, at this very moment, might have been skimming down a review of a book called “Twenty Years of Groundbreaking US Game Shows.”

Simply put: Jan. 10, 1999 was D-Day for TV.

It’s fitting that this moment in TV history and its seismic aftermath should be commemorated and chronicled by two men who were with The Sopranos from the very beginning, and who between them have spent two decades delineating its multi-layered, mesmerizing genius.

Zoller Seitz and Sepinwall bring not only a fierce love and admiration of the series to their collaboration but also a wealth of experience and knowledge: Seitz is editor-at-large for RogerEbert.com, as well as the TV critic for New York magazine and Vulture.com. Sepinwall is the chief TV critic for Rolling Stone, and previously worked for both Uproxx and Hitfix. He’s also the author of a clutch of highly-regarded books on TV, among them The Revolution Was Televised. Both men were critics at the Newark Star-Ledger throughout the time that The Sopranos was on the air. The Star-Ledger, of course, is the paper that usually slammed on to Tony’s driveway at the beginning of (almost) every season of The Sopranos, and of which Tony himself was an avid reader.

The Sopranos Sessions is essentially a box-set in book form, both in terms of how it’s presented, and in the behavioral mindset I’m certain it will inspire in its readers. Just one more page, you’ll promise yourself, just one more chapter, and then I’ll put it down. Before you know it, it’s three o’clock in the morning, you’ve binged half the book, and you’re on the phone to your estranged wife, with Lionel Ritchie ringing in your ears.

Further Reading: What a Sopranos Prequel Might Look Like

The book is divided into three parts. There are the recaps, analyses, and deconstructions, so engagingly written and thought-provoking that you’ll feel like you’ve actually watched the episodes. Then there are the “bonus features”: previously published articles about the show and its cast; ruminations on the show’s relevance to and connection with the wider culture, all of which were written by the authors between 1999 and 2007; and, finally, the piece de resistance, a glut of brand new and in-depth interviews and discussions with Chase on all aspects of the show, with inevitable segues into pop-culture, history, music, cinematography, the art of showrunning, philosophy, psychology, sickness, sin, and the minutiae of life itself.

Chase is an auteur extraordinaire, an almost holy figure. If The Sopranos is a church, and few are broader or more ornate, then Chase is undoubtedly both the head of that church and its God. Sometimes his sentences demand the sort of close examination normally reserved for entire episodes of his magnum opus. His mind appears to be in constant flux, constantly revising, reframing, and re-interpreting his own motivations and understanding, ceaselessly interrogating the meanings behind his words and actions. It’s not just that there was no better person than Chase to bring The Sopranos to life; it’s simply that there was no other person who could possibly have done it. His genius bleeds into and out of every blessed moment.

Through Chase’s conversations with Seitz and Sepinwall – as funny, insightful, frustrating, illuminating, and erudite on all sides as you’d expect – we come to realize that true genius is kaleidoscopic and mystical, and sometimes feels closer in character to the big bang than a controlled explosion. Chase can’t always account for the genesis of some of the show’s deepest and most pivotal moments, or else shrugs and says it was just luck. He brings great clarity to some aspects of the show – for instance, we discover that Ralph definitely burned Pie-O-My (“You never got the goat thing?” he chides) – and veils others in ever greater cloaks of obscurity.

Further Reading: Remembering the “Other” Characters Gandolfini Played on The Sopranos

Anyone hoping for some final closure on the whole “Is Tony dead?” question may find themselves pleasantly surprised… and then hopelessly disappointed. And then pleasantly surprised again. And then, well, you get the idea. It’s a journey that seems destined to go on and on and on and on…

Or is it?

Whichever side you’re on (or perhaps you’re on neither side and think that the whole question of Tony’s fate is either a distraction from proper contemplation of the show’s overarching themes or an artsy gimmick unworthy of further consideration) you’ll find the Freudian slip that prompts Chase to aim an exasperated “Fuck you guys” in the direction of an astonished Seitz and Sepinwall – and its fallout – very interesting indeed.

As Laura Lippman says in the foreword to The Sopranos Sessions, there are levels of Sopranos obsessiveness. I’ve always considered myself in the higher ranks of obsession, having watched each episode of the show more times than I could count. I’ve pondered and pored over its myriad meanings and symbols, and I’ve proselytized in its name. But Seitz and Sepinwall make me feel like a newbie, a late-night channel-flicker. Their insight is staggering and immersive, though still entirely accessible to those in the earlier stages of Sopranos-based obsession.

Further Reading: 9 TV Shows Developed from Abandoned Movie Scripts

Seitz and Sepinwall’s ability to tease out themes, intuit connections, analyze at the atomic level, and discover hidden meanings in the material frequently had me lowering the book in slack-jawed admiration, from the revelation that eggs always augur death to the deliciously meta reframing of season three’s “Mr. Ruggerio’s Neighborhood”; and to passages like the below, which I’m going to reproduce verbatim so that you can revel in the Ouroborotic beauty of the duo’s reasoning:

The architecture of the Tony/Livia relationship is astonishingly intricate in retrospect. It’s driven not just by straightforward dialogue and definitive actions but subtle psychological and literary details, including the recurring talk of infanticide, Tony’s two dreams about mother figures (the duck and Isabella), and the way that the idea of asphyxiation is woven throughout the season. Tony feels suffocated by his mother; the resultant panic attacks make him feel like he’s suffocating; he now intends to deal with the problem by suffocating his mother (poetic justice), but arrives to find her lying on a gurney, a plastic mask on her face providing constant oxygen. (“That woman is a peculiar duck,” Carmella tells Tony. “Always has been.”)

The real joy of the show, and the joy of this book, lies in the act and art of interpretation. The Sopranos has always invited this response – it’s pretty much built into the premise – because psychiatry, much more than gangsterdom, is, and always has been, at the show’s heart – a ceaseless search for answers to the great conundrums of life, the universe, and everything (and nothing); questions for which there are rarely easy answers, and sometimes no answers at all. Just more questions carried across the sky by a great wind. Who am I? Where am I going?

Tony Soprano wasn’t alone in therapy. Arguably, we were in there with him. Dr. Jennifer Melfi, Tony’s long-standing and long-suffering psychiatrist, was the Greek chorus, our entry-point into Tony’s world, but she was also, in a sense, our psychiatrist. She interrogated our motives for watching the show, just as much as she questioned her own motives for continuing to treat Tony. Or, as Seitz and Sepinwall put it: “The series is sometimes as much about the relationship between art and its audience as it is about the world the artist depicts.”

Further Reading: The Sopranos Prequel Film Will Feature Young Tony Soprano

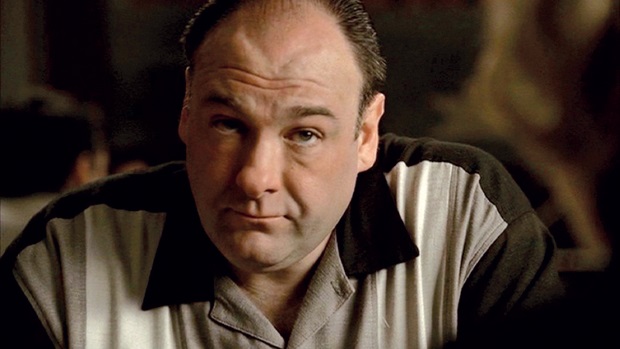

We saw more of Tony’s life than Melfi ever did or could – the very worst of his trangressions, from the inconsiderate to the murderous, and still kept following him down the rabbit-hole of his broken soul. Much of the reason why we did this – exemplary writing aside – was Gandolfini, the jaded, gentle giant with the hang-dog face and the little boy’s heart, whose “humanity shone through Tony’s rotten facade” to gift us what was, in all likelihood, the most complex, compelling, complete, and completely human character ever to be committed to the screen (I’m not ashamed to admit, not being a gangster myself, that Chase’s eulogy to Gandolfini, included in this book, made me cry).

I haven’t re-watched The Sopranos for years, but that’s set to change as a result of The Sopranos Sessions, which has re-invigorated – and deepened – my love for the show. You may not be as intense a fan of The Sopranos as I am, and that’s okay. This is a perceptive, lucid, engaging, and above all versatile book that could serve as a series companion, a read-me-in-the-toilet tome, or a TV-studies textbook depending upon your level of interest, and fluency, in the show. There’s something for everyone.

All legacies fade, but until Chase’s prediction for The Sopranos comes true – not for another few million years or so – Seitz and Sepinwall deserve to be part of that legacy.

The Sopranos Sessions is out now. You can buy it on Amazon.