Star Trek Villains Who Actually Had a Point

Maybe the Final Frontier doesn’t have any baddies. Maybe these villains of the Star Trek universe were just a bit misunderstood.

This article contains spoilers for various parts of the Star Trek franchise.

Last fall, airing just a few weeks apart, both Star Trek and Star Wars debuted season premieres of new streaming TV episodes in which the heroes of each show had to fight a giant, legless worm-monster. In Star Trek: Discovery’s “That Hope Is You Part 1,” it was the deadly Tranceworm, while The Mandalorian’s “Chapter 9: The Marshall” had the murderous Krayt Dragon. The differences between the Final Frontier and the Faraway Galaxy could not have been made clearer by these dueling beasts: in Mando, the plot involved killing the monster by blowing up its guts from the inside, while in Disco, Book taught Michael Burnham how to make friends with it.

The Trek universe deals with the concept of evil a little differently than many of its famous genre competitors. There is no Lex Luthor of the Federation. Palpatine doesn’t haunt the planet Vulcan. The Klingons have no concept of “the devil.” (At least in The Original Series.) This isn’t to say Trek doesn’t have some very memorable Big Bads, it’s just that most of the time those villains tend to have some kind of sympathetic backstory. Even in the J.J. Abrams films!

So, with that in mind, here’s a look at seven Star Trek villains who maybe weren’t all bad, and kind of, even in a twisted way, had a point…

Harry Mudd

In Star Trek: The Original Series, Harry Mudd was presented as a straight-up con-man, a dude who seemed to be okay with profiting from prostitution (in “Mudd’s Women”) and was also down with marooning the entire crew of the Enterprise on a random planet (in “I, Mudd”). He’s not a good person. Not even close. But, he does make a pretty could case against Starfleet’s lack of planning. In the Discovery episode “Choose Your Pain,” Mudd accuses Starfleet of starting the war with the Klingons, and, as a result, putting the larger population of the galaxy at risk. “I sure as hell understand why the Klingons pushed back,” Mudd tells Ash Tyler. “Starfleet arrogance. Have you ever bothered to look out of your spaceships down at the little guys below? If you had, you’d realize that there’s a lot more of us down there than there are you up here, and we’re sick and tired of getting caught in your crossfire.”

Seska

At a glance, Seska seems pretty irredeemable. She joins the idealistic Maquis but is secretly a Cardassian spy. Once in the Delta Quadrant, she tries to screw Voyager as much as possible, mostly by hooking up with the Kazon. That said, Seska is also someone caught up in hopelessly sexist, male-dominated power structures and does what she has to do to gain freedom and power. The Cardassian military isn’t exactly enlightened nor kind, so the fact that Seska was recruited into the Obsidian Order in the first place certainly explains her deceptive conditioning. You could argue that Seska could have become a better person once she had Captain Janeway as an ally, but, the truth is, she was still a spy caught behind enemy lines, but suddenly without a government to report back to. So, Seska did what she had to do to survive, even lying to Chakotay about having his child. The thing is, again, outside of Starfleet, Seska is at the mercy of the sexist machinations of the Kazon, so again, she’s kind of using all the tools at her disposal to gain freedom. Had Voyager not gone to the Delta Quadrant, and Seska’s villainy may have been more clear-cut. But, once the reason for her espionage becomes moot, her situation gets more desperate, and, on some level, more understandable.

Charlie Evans

In The Original Series, Kirk loves telling humans with god-like powers where to shove it. In “Where No Man Has Gone Before,” he phasers Gary Mitchell and buries him under a rock. But, in “Charlie X,” when teenager Charlie Evans also gets psionic powers, Kirk does a less-than-a-great job of being a good role model. For most of the episode, Kirk tries to avoid become Charlies’ surrogate parent, and when he does try, it results in an embarrassing overly macho wrestling match featuring those famous pink tights.

Charlie was a deeply troubled human being, and there was no justification for him harassing the crew and Janice Rand in specific. But, angry, kids like Charlie have to be helped before it gets to this point. Kirk mostly tried to dodge the adult responsibility of teaching Charlie the ropes, and only when some friendly aliens arrived, did everyone breathe a sigh of relief. But, don’t get it twisted, those aliens are basically just social workers, doing the hard work Starfleet is incapable of.

The Borg Queen

Because the origin of the Borg Queen has dubious canonical origins, all we were told in Voyager is that she was assimilated as a child, just like Seven of Nine. As Hugh and Jean-Luc discuss in the Picard episode “The Impossible Box,” basically, everyone assimilated by the Borg, is, on some level, a victim. The Queen was never presented this way in either First Contact or Voyager, but, at one point, writers Judith and Garfield Reeves-Stevens had pitched a story for Enterprise which would have featured Alice Krige as a Starfleet medical technician who made contact with the Borg.

Because both Alice Krige and Susanna Thompson played the Borg Queen, it’s possible the backstories of each Queen is different and that maybe they aren’t the same character. Either way, assuming the Borg Queen retains some level of autonomy relative to other drones (likely?) then she’s pretty much making the best of a bad situation. In fact, at the point at which you concede the Borg are unstoppable, the Queen’s desire to let Picard retain some degree of his independence as Locutus could scan as a kind of mercy. The Borg Queen actually thinks she and the Borg are making things simpler for everyone. And with both Data and Picard, she tried to make that transition easier and, in her own perverse way, fun too.

Ossyra

Yes, we saw Ossyra feed her nephew to a Trance worm, and we also saw her try to kill literally everyone on the USS Discovery, including Michael Burnham. However, in the middle of all of that, Ossyra did try to actively make peace between the Emerald Chain and the Federation. And, most tellingly, it was her idea. Ossyra also pointed out one of the most hypocritical things about the United Federation of Planets: the fact that Starfleet and its government rely on capitalism without actively acknowledging it. Essentially, Ossyra was saying that the ideals of the Federation are great, but the Federation has all kinds of dirty little secrets it doesn’t want to talk about. In her meeting with Admiral Vance, pretty much everything she said about the Federation was true—and her treaty proposal was fair.

The only snag: she wouldn’t turn herself over as a war criminal. Considering the fact that the Federation made Mirror Georgiou into a Section 31 agent, despite her war crimes in another universe, this also seems hypocritical. Why not just do the same thing with Ossyra? Tell everyone she’s going to prison for war crimes, but make her a Section 31 agent instead? Missed opportunity!

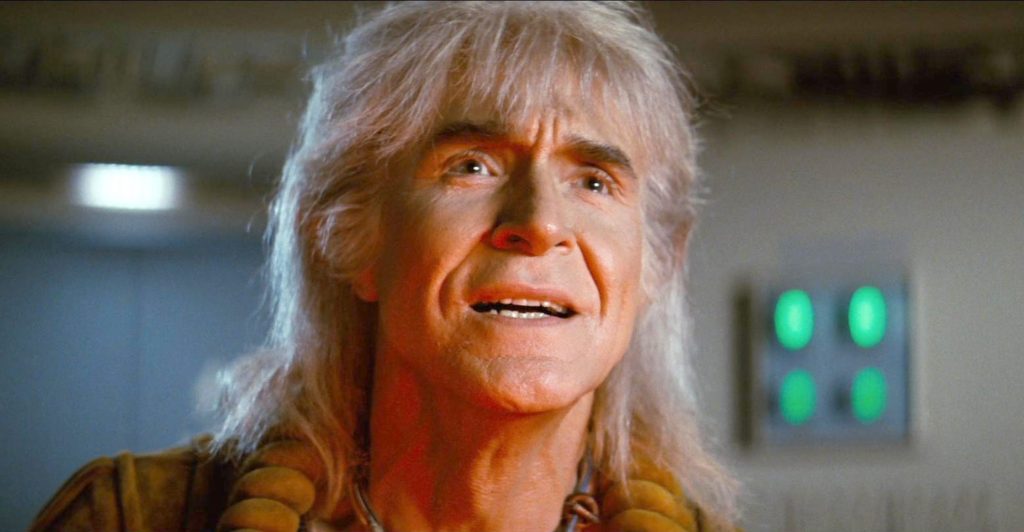

Khan

Khan was genetically engineered by wacko-a-doodle scientists at the end of the 20th Century. At some point on Earth, he became a “prince” with “power over millions.” But, as Kirk notes in “Space Seed,” there were “no massacres” under Khan’s rule, and described him as the “best of the tyrants.” Kirk’s take on Khan in “Space Seed” is basically that Khan was an ethical megalomaniac. Most of what we see in “Space Seed” backs this up. Khan doesn’t actually want to kill the crew, and stops short of doing it when he thinks he can coerce them instead. His only focus is to gain freedom for himself and his exiled fellow-Augments. In the Kelvin Universe timeline, Khan’s motivations are similar. Into Darkness shows us a version of Khan who, again, is only cooperating with Section 31 because he wants freedom for his people. Sure, he’ll crush some skulls and crash some starships to get to that point, but in his dueling origin stories, Khan is, in both cases interested in freedom for his people, who, are by any definition, totally persecuted by the Federation.

Khan is still a criminal in any century. But, we only really think of him as a villain because he goes insane in between the “Space Seed” and The Wrath of Khan. The Khan of The Wrath is not the same person we met in “Space Seed.” As he tells Chekov, “Admiral Kirk never bothered to check on our progress.” Had Kirk sent a Starfleet ship to drop in on Khan and his “family” every once in awhile this whole thing could have been avoided. In the prime timeline, Khan goes nuts because Ceti Alpha VI explodes and nobody cares. In the Kelvin timeline, Admiral Marcus blackmails him. Considering that Khan is Star Trek’s most famous villain, it’s fascinating that there are a million different ways you can imagine him never getting as bad as he became. In “Space Seed,” he and Kirk basically part as friends.

Q

In “Encounter at Farpoint,” Q accuses humanity of being “a savage child race.” And walks Jean-Luc Picard through the various atrocities committed by humanity, through the 21st Century. Picard kind of shrugs his shoulders and says, “we are what we are and we’re doing the best that we can.” When we talk about the philosophy of Star Trek, we tend to give more weight to Picard’s argument: the idea that by the 24th century, humanity has become much better, in general than it is now. But, the other side of the argument; that there’s a history of unspeakable violence and cruelty baked into the existence of humanity, is given less weight. We don’t really listen to Q when he’s putting humanity on trial, because we can’t see his point of view.

But, because Q wasn’t a one-off character, and because he said “the trial never ends” in the TNG finale, he’s actually not really a villain at all. Q exists post-morality, as we can imagine it. His notions of ethics are far more complex (or less complex) than we can perceive. Q is one of those great Star Trek characters who is actually beyond reproach simply because we have no frame of reference for his experiences or point of view. In Voyager, we also learned that even among other members of the Q Continuum, Q was kinder, with a more humanitarian approach to what he might call “lesser” lifeforms. If Q is villainous, it’s because of our definitions of villainy. Of every Star Trek antagonist, Q is the best one, for the simple fact that he’s not a a villain at all.

Which Star Trek villains do you think had a point? Let us know in the comments below.