She-Ra Season 5 Moves Queer Representation A Huge Step Forward

By getting two of its major characters together, She-Ra season 5 has pushed the boundaries of what’s allowed in children’s entertainment.

Warning! This article has spoilers for the entire final season of SHE-RA AND THE PRINCESSES OF POWER. Turn away if you haven’t seen it already!

When Den of Geek called She-Ra and the Princesses of Power the next step in queer representation back in 2018, just before it premiered, we had no idea how fully the show would live up to that designation. The answer? So much more than we even hoped. The series is helmed by Noelle Stevenson, a queer woman, and has two supporting queer characters (Spinerella and Netossa) that are clearly a couple. This alone was already a win for queer fans, as queer representation in media aimed at children has proven to be minimal to non-existent.

Over the course of the first four seasons of the series, more representation was introduced, including two gay dads for Bow, one of the main characters. It wasn’t as much as fans would have liked and Netossa and Spinerella never seemed to get as much focus as queer fans wanted. They got some time to shine, but they weren’t main characters, so they were only in an episode or two a season.

That changes in the final season, which just dropped on Netflix. Not only do Netossa and Spinerella get much more screen time, but they kiss multiple times and are revealed to be married! They also get an arc in the season in which Netossa desperately tries to save Spinerella from the evil Horde Prime’s mind control. It leads to some extremely powerful moments for the couple and, had that been their entire presence in the season, would have been a great step forward for queer representation in queer media.

However, the finale blew all expectations out of the water. Adora and Catra, the two main characters of the series, declare their love for each other and kiss. This doesn’t just come out of nowhere. Over the course of the series, the two seemed to have something going on that was deeper, or at least different, than the relationship of two friends separated by war who were desperate to try and convince the other to leave the opposing side. Catra especially seemed to delight in flirting with Adora.

As obvious as it might have seemed to fans, there was no guarantee the two characters would actually end up together. Many other shows, for both adults and children, have had queer subtext that is never brought to the forefront. Adora and Catra could have just ended the series as very good friends and while it would have been disappointing it wouldn’t have been unexpected.

The fact they get together is huge. While it did take until the final episode of the series, it isn’t ambiguous at all. They don’t just say, “I love you,” they also kiss and lovingly hold each other. This is a huge step forward from the finale of The Legend of Korra in 2014, one of the first big moments of queer representation in American children’s animated media. There, the main characters of Korra and Asami held hands and looked lovingly at each other, echoing an early wedding scene between two straight characters. It might not seem like much, but, at the time, it was gigantic.

Korra co-creator Bryan Konietzko revealed that there were limits to how far they could go with portraying the couple as queer, although they only asked about this during a late stage of the production of their finale. Konietzko even admitted that this wasn’t a slam-dunk for queer representation but he hoped it was a “somewhat significant inching forward.”

It certainly is and, in the years since, more queer characters have started to show up in children’s animation. Steven Universe introduced multiple queer characters and even had two main women characters get married on screen in 2018. Yes, they were technically gemstones that took on physical form, but it was still two women getting married in a children’s animated series. That was huge, especially as the characters involved had big arcs before and after that.

The wins for both those series and others were big, but what perhaps helped those series along in allowing queer representation was the fact that they were original characters that weren’t based on existing intellectual property and the selling of toys. Traditionally, any series that has selling toys as a main focus steers away from queer characters in an attempt to not cause any “controversy” and maximize sales. Also, characters from legacy IP’s have more expectations from executives attached to them, meaning fewer risks can be taken. That didn’t mean there weren’t still battles to be fought, as both the creators of Korra and Steven Universe creator Rebecca Sugar have discussed.

This makes She-Ra’s ultimate revelation that Adora and Catra are queer different because these two are characters from a huge IP. She-Ra was originally created in the ’80’s to sell toys. While she’s never gotten quite as much attention as He-Man (the original series that later spun off She-Ra), she’s still a major intellectual property. She’s a pop culture icon.

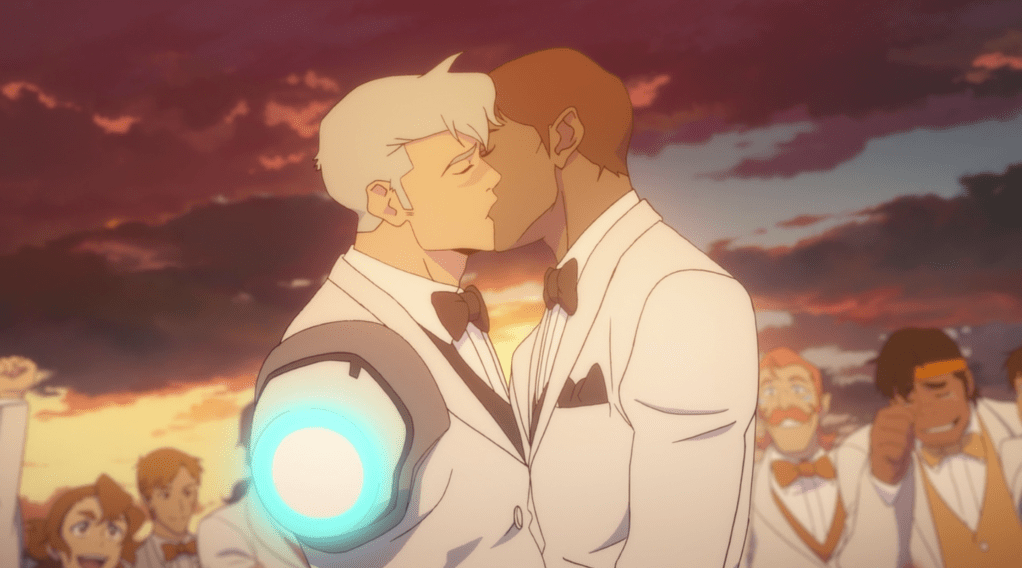

Making a legacy character gay is rare and even more so if it’s a main character. This was seen in a similar action adventure series for children, Voltron: Legendary Defender (also produced by DreamWorks, the company behind She-Ra.) That series, debuting in 2016, revealed that Shiro, one of the main Voltron pilots, was a queer man but this was barely spoken about in dialogue. It was only majorly shown in one flashback scene as he was breaking up with a man. In the same season, that former partner was killed in a sad example of the “bury your gays” trope. Thankfully, in the final episode of the show, we got to see Shiro marry a man and the two kissed.

Joaquin Dos Santos, one of the show runners of that series, discussed that they had to navigate a “fine line” when it came queer characters. This was especially true for Voltron which was, as Dos Santos, described: an “action adventure/product driven/traditionally boys toys” series. This placed limitations on the series imposed by studio executives that were hard to break.

It also hampered anything the creative team wanted to do with the character. When they attempted to change Shiro’s role in the show, which involved writing him out of the story for at least a season, this was blocked by the executives because, as fellow Voltron showrunner Lauren Montgomery described, “Shiro’s gotta sell toys.”

Dos Santos later added that “it’s frustrating to deal with some of those things when we had creative ideas that we wanted to extend a bit further. There’s a lot of moving parts to an IP this big. Concessions have to be made.”

This is also true for revealing Shiro was queer, which was originally supposed to be done in season two of Voltron, but was shunted all the way back to season seven and then only explicity shown in the series finale. It wasn’t perfect, but it was still a step forward. Shiro was a disabled queer man of color in a boys action series meant to sell toys. That’s still very rare and there’s a much larger discussion to be had about how queer men are allowed to be portrayed in children’s media, especially action series meant to sell toys.

Still, after this happened with Shiro, things seemed to change at DreamWorks in particular. She-Ra premiered, headed by a queer woman, and included queer women as characters. Kipo and the Age of Wonderbeasts (another DreamWorks series) revealed that one of its main characters of color was gay. And now, She-Ra.

She-Ra is a legacy IP brand meant to sell toys yet the two main characters ended up together in the end. Comparing it to Shiro from Voltron? This is a huge step forward and hopefully it means that DreamWorks (and other companies) learned its lesson from what happened on Voltron. Perhaps the work of the Voltron producers helped open the door for not only She-Ra but Kipo as well.

Whatever the case, before She-Ra premiered, Noelle Stevenson did credit everyone who fought for queer representation before her (not just at DreamWorks but in general) for being able to make She-Ra’s wide range of queer representation possible. She also stated that the battles for queer representation aren’t over and it’s “never going to be easy… but it’s something that’s very important to do.”

In a perfect world, Catra and Adora would have gotten together earlier in the series or Adora would have been allowed to express her identity as a queer woman. We’re not there yet, sadly, but, by ending She-Ra in this way, we’ve taken another step forward in representation for queer characters. We also can’t discount Spinerella and Netossa. They weren’t main characters but having two women portrayed as both married and as action heroes is important. We need more characters like them. Hopefully, the series that come after She-Ra will be able to do even better.

It must also be noted that two of the series that have had the best track records with queer characters, She-Ra and Steven Universe, are both helmed by queer creators. This doesn’t automatically mean they got to put whatever they wanted into their shows but it meant they were better situated to do a goodr job at portraying queer characters in ways that aren’t offensive or that unintentionally fall into offensive tropes.

The acclaim and success that both Steven Universe and She-Ra have enjoyed prove that more diverse queer voices need to heard in this industry. We’ve only just begun the process and can still do better. Still, that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t celebrate what we have and the ending of She-Ra is truly something to get excited about. It points to a better and brighter future for everyone. As Stevenon said back before the show debuted,

“As a gay woman, it’s something I think is really important to feature in kids animation. Just to show the richness of experience in the world and the different ways that characters can love each other.”