Life Finds a Way: How Netflix’s Life on Our Planet Brought Prehistoric Animals Back to Life

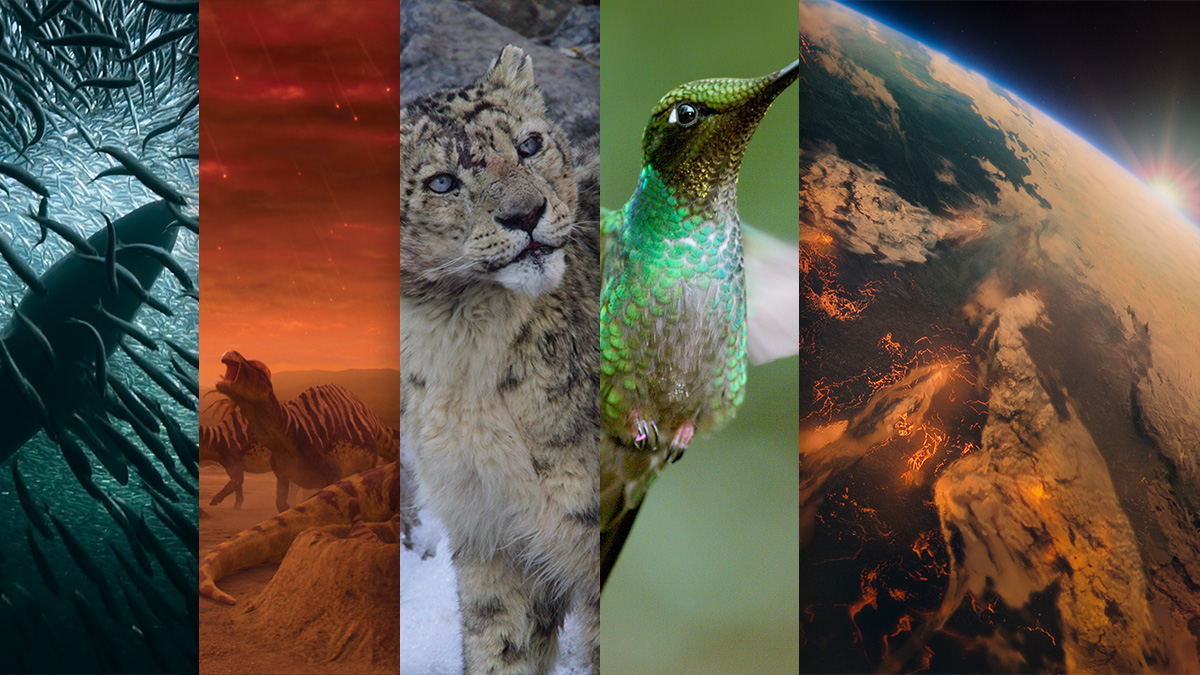

Fusing stunningly shot modern nature with computer-generated prehistory, the making of Life on Our Planet was as ambitious as the story it tells.

This article is presented by

Jeff Goldblum’s iconic assertion in 1993’s Jurassic Park is not just one of the most instantly quotable lines in cinema history; it also neatly sums up the four-billion-year history of life on Earth in four short words (five if you count the none-more-Goldblum “uh” in the middle). Of course, the reality is far from that simple.

Now, 30 years later, the makers of Netflix’s phenomenally successful nature doc Our Planet have joined forces with the technical wizards at Industrial Light & Magic for an ambitious fleshing-out of that gigayears-old story of evolution.

A series nearly five years in the making, Life on Our Planet blends groundbreaking visual effects with state-of-the-art nature photography to tell the epic tale of how life has, indeed, found a way.

Employing some Christopher Nolan-esque time-hopping and framing the action around five major mass extinction events, the series draws evolutionary lines between the lost beasts of yesteryear and some of today’s most fascinating creatures.

“We’d just finished the first season of Our Planet and started to think what the next big series could be,” says Keith Scholey, one of the series producers. “It was at this point that we wondered about tackling the biggest story of all: the story of life.” Scholey and fellow producer Alastair Fothergill, founders of wildlife film production outfit Silverback, had worked with their idol David Attenborough several times before on series such as Our Planet. And fittingly, it was the natural history legend who provided inspiration for what was to become the duo’s most ambitious project yet.

“We remembered [Attenborough’s] first-ever series, Life on Earth, which was way back in 1979 when Alastair and I were university students,” says Scholey. “That series made waves at the time, but no one had touched that subject since. The reason why it has been ignored is that it’s too hard! It’s too big a story to tell. But we love a challenge, and feeling that we could overcome those hurdles, we decided we must try.”

“Despite the fact that the original Life on Earth is dated in some ways, such as the cinematography and lack of CGI, it’s a totally gripping story,” adds Fothergill. “We wanted to take that and elevate it to a new level.”

The pair were joined in that quest by fellow series producer Dan Tapster, who’d also been in awe of Life on Earth as a youngster and who quickly became excited by the project’s narrative potential. “To have the chance to once again tell the story of how life originated, and then evolved, and then was destroyed only to go again was too good to resist,” he recalls. “I could see early on that we could make this a binge-worthy series, with enticing starts and edge-of-your-seat cliffhangers.”

Right from the get-go, the producing trio knew that the series would require three key components to work. First, the show needed stunning, cutting-edge nature photography, not only to capture the beauty and drama of today’s animal kingdom but also to provide realistic environments for the show’s long-extinct cast of critters. Second, there was the push for scientific authenticity, utilizing the latest research gleaned from what the filmmakers refer to as a current “golden age of paleontology.” And third, and perhaps the most tricky, was that there would be a heavy element of computer-generated imagery involved.

“We realized after seeing [Ang Lee’s 2013 drama] Life of Pi that it was finally possible to recreate animals in a way that was photoreal, where you wouldn’t be able to tell the difference between VFX and real life,” says Scholey. “That was the moment where we realized we stood a chance.”

“For a long time, one of the big challenges for CG was rendering hair and feather details,” Fothergill explains of the team’s initial reservations. “People have been doing skin and scales for quite some time; that’s why dinosaurs have been brought to life relatively successfully. But seeing the tiger in Life of Pi was what really made us think fur and even feathers were now possible—and that was crucial because while Life on Our Planet has some amazing scaly dinosaurs, there are a lot of other extraordinary prehistoric animals.”

Enter executive producer Steven Spielberg and legendary effects house ILM, both of whom have form when it comes to recreating creatures of the past onscreen. But even with those big guns on board, the producers were committed to their vision that the CGI, while a massive part of the series’ appeal, shouldn’t steal the show—and that the fusion of real and photoreal should be “seamless.”

“We went into the series knowing that if you have too much CGI, the audience can drift off into feeling it’s fiction rather than fact,” Scholey says. “We deliberately chose to integrate natural history and CG to give the series veracity. When you’re brought back into reality with an up-to-date scene of a real-life animal, it absolutely helps the overall narrative. And finding that balance was probably the hardest thing to do.”

“Each episode contains around 30 to 40 percent CGI, and the rest is the very best in classic, blue-chip nature cinematography,” confirms Fothergill. “Right until the end, Keith, Dan, and I were very nervous as to whether that conceit would really work—not just the visual conceit, but also the intellectual conceit. It was a massive relief to us that it did, and I think that’s what makes Life on Our Planet completely unique.”

Recreating a Lost World

Luckily, that conceit was one that ILM also fully bought into. “We were in from the beginning,” says the series’ VFX supervisor, Jonathan Privett. “I was really excited by the fact that we were going to make it like natural history. The prospect of going out to places around the world, filming these incredible shots, and then being able to put prehistoric creatures in them was amazing. I’ve always been a huge fan of the natural world, and I remember being glued to the screen watching [Attenborough’s original Life on Earth], so having a chance to work on something like this was really a dream come true.”

All of Life on Our Planet’s VFX sequences —with the notable exception of one—were animated against real-life “plate” shots filmed in real-world locations. Not only that, but the producers wanted the prehistoric and modern-day scenes to look like they were shot in the same way, too. “Natural history has a visual grammar, and we needed to impose that on our visual effects,” says Tapster. “So we embraced an idea called time-travel cinematography. When it came to planning the camera work of each scene, we would sit down with [cinematographer Jamie McPherson] to devise how we would shoot it if we literally had access to a time machine. For instance, you wouldn’t shoot a T-Rex on a Steadicam from 3 meters away because you’d get eaten….”

The location photography and VFX teams worked closely together to achieve the sense of realism that the producers were looking for, although Privett admits that filming this way did prove more technically challenging than simply creating everything from scratch. The VFX chief had to extract detailed 3D information from the plate footage shot by McPherson and then produce accurate models of the environments via a tricky process called photogrammetry before the CG creatures—or “assets”—could be set free to roam about them, making the process “harder and more time-consuming than having done it as a completely virtual world.”

Logistical restrictions meant that certain environments required slightly more CG augmentation than others—the first episode’s standout T-Rex versus Triceratops chase sequence, for example, was filmed in a “car park in Surrey” rather than a more exotic locale in order to accommodate the necessary high-speed tracking shots, with ILM later adding in foliage and trees to create a lush, late Cretaceous meadow.

Impressively, though, there is only one fully computer-generated sequence in the entirety of the series’ eight chapters: a scene featuring the prehistoric deep-sea predator, Dunkleosteus—which Tapster calls “the biggest, most angry-looking fish there’s ever been” (“Our paleontologist said it’s the only animal he’s ever studied that he’s really glad is extinct because it’s too terrifying for its own good,” he reveals).

“Even the other underwater sequences, we did shoot for real,” Privett says, explaining that Dunkleosteus’ habitat proved more difficult because of the vast expanse of, well, nothing. “It’s hard in the deep blue because obviously there’s no [detail] to track in live-action photography. So we made that whole underwater environment, and we did a lot of research on the science of color and light absorption at that depth to make it work in a realistic way.”

Fantastic Beasts

Placing the prehistoric animals in live-action locations was only half of the challenge, though—the other was creating the beasts themselves. The filmmakers worked with lead scientific researcher Dr. Tom Fletcher and an army of consultants to help whittle down a huge list of potential creatures to around 65, each chosen for their value in driving the narrative forward and hitting “the main beats in the story of life,” according to Fothergill.

With the producers setting themselves a high bar of presenting “the most accurate VFX creatures there’s ever been,” each asset had to be thoroughly researched in order to provide ILM with every possible detail. The latest fossil evidence was used to inform the creature designs, movements, and behavior, helped by a technique called “phylogenetic bracketing”—studying an extinct animal’s closest surviving descendants to fill in the gaps. Each asset ended up with a 60-page “fact file,” says Tapster.

Privett describes bringing these creatures back to life as a “massive undertaking”—a “totally immersive” operation that took more than four years to complete. “We have twice as many creatures [here] as you’ll find have ever been made in the Jurassic World franchise,” he says of the show’s ambitious nature, adding that there were a total of 60,000 VFX shots submitted for review (there are 867 final shots across the completed series). And with the small but focused ILM team forced to work remotely for large parts of the production thanks to the arrival of a pandemic, the process of creature creation certainly wasn’t plain sailing. “It did come with quite a lot of creative challenges… and I think that we had to push harder to overcome those challenges that you get when people aren’t in a room together.”

Challenges aside, though, the results more than paid off. That much was evident early on, with the very first VFX scene to be completed: a clan of Lystrosaurs—a cute, pig-like creature notable story-wise for being one of the only survivors of Earth’s volcano-charged third mass extinction—and their first encounter with the fearsome, crocodile-like Erythrosuchid. “We went to Chile to shoot that,” says Privett. “So we had these amazing background plates. And the Lystrosaurus and Erythrosuchid were the first assets that we built; that was us kind of feeling our way, I suppose. But they did get a lot of love as a result of being first up. When I saw the first render, I thought, ‘Yeah, this is gonna be great.’ The Atacama [desert] is such a wonderful environment to explore, and the creature looks so fabulous in it.”

When the sequence was finished in early 2021, the time came for it to be shown to Mr. Spielberg. “We knew at some point that Steven would be looking at that stuff because it was the first thing that we shot,” Privett continues. “So a lot of care and attention went into it.” The producers shared ILM’s sense of anticipation…. “[Amblin Television co-presidents] Darryl Frank and Justin Falvey suddenly announced that they were so pleased with it, they wanted to immediately ‘show it to Steven,’” remembers Tapster. “At that point, all of us who were involved were simultaneously excited and terrified. After an anxious, sleepless night, I awoke to an email simply saying: ‘Steven loves it.’ I’ve printed that and kept it for posterity!”

It wasn’t just Spielberg who was a fan; the sequence impressed the academics, too.

“The Lystrosaurus asset was deemed to be so accurate by the paleo consultant that he asked ILM to borrow it to use in a scientific paper,” Tapster enthuses. That must have been a nice bit of feedback for the VFX team, right? “In a way, it’s the ultimate accolade, isn’t it—for someone whose life’s work is looking at these creatures to go, ‘Yeah, that’s the most accurate representation that we’ve had,’” says Privett. “So yeah, very chuffed.”

The Lystrosaur sequence is also a good example of some fun Easter eggs the VFX team sprinkled throughout the series, paying homage to ILM’s Jurassic heritage, among other things: as the Erythrosuchid stalks its prey, look closely, and you may spot some subtle nods to a certain “raptors in the kitchen” scene. “That’s one of them, definitely—that sequence is exactly inspired by that,” Privett smiles. “There aren’t loads [of Easter eggs], but there’s the odd cheeky one or two.”

A Mammoth Task

One of Life on Our Planet’s other standout sequences showcases the sheer technical innovation on display. Set during the Ice Age, a scene that depicts a pack of cave lions squaring up to a herd of giant mammoths on a chilly tundra was the most expensive—and ambitious—of the whole production, becoming a calling card for what the series was able to achieve.

“That’s definitely the most complicated scene in the show,” says Privett. “We’re animating multiple creatures against empty plates filmed in Iceland. Both creatures are furry; they’re in the snow, which is sticking to them, and they’re moving in high winds. So it’s a full-on extravaganza.” Luckily, the fact that both species have close modern relatives in the form of lions and elephants meant the VFX artists could choreograph the animals’ movements more easily than some of the series’ other prehistoric stars. But creating realistic hides, especially given the complex weather at play, brought an even bigger challenge. To overcome it, Privett looked to another ILM project: The Mandalorian.

To create the Mudhorn, a huge rhino-like beast with a thick, wooly, mud-soaked coat, the Star Wars show’s VFX team had “used a more efficient pipeline than the one that has been historically used at ILM,” Privett explains. It was a process that would enable the Life on Our Planet animators to combine the various VFX elements in a more “holistic” way. “The previous system didn’t allow for a lot of the elements to be joined together—it was done in silos, so the fur was separate from the snow, which was separate from the render. This new solution brought all those elements together, which enabled us to put snow on the fur and the fur to react to the wind and the snow and the fur to stick together. It was definitely a step forward and much more user-friendly.”

The result is one of Privett’s favorite sequences of the series. “It took a long time to get it 100 percent right, but I’m really proud of it. The creatures in it look superb.” The scene, he says, is also a good example of how the team kept standards high while finding new, more efficient ways of doing things.

“I think the interesting thing about Life on Our Planet is it brings some of that level of Jurassic Park quality to something that previously, even with an enormous budget, would probably not have been achievable. So with that challenge, ILM has really upped its game in terms of what it can deliver.”

Meticulous research, stunning real-world photography, and innovative VFX are all well and good, but the final piece of the puzzle when it comes to any nature documentary is an expert narrator who can tie it all together. And if you’re going to be homaging one of Sir David Attenborough’s seminal works, you’re going to need a voice with a similar level of gravitas. For Life on Our Planet, that voice is none other than Oscar-winning Hollywood legend Morgan Freeman.

“Great narrators don’t just read words on a page; they tell stories,” says Scholey. “With Morgan, you are so taken in by his storytelling skills that he draws you into the film.” Fothergill adds that Freeman has “become something of the voice of God, and so to tell the story of life, a story that is big, profound, dramatic, and relevant, his voice fits perfectly.”

Tapster agrees that Freeman “completed the series,” bringing not just his dulcet tones and storytelling prowess but also his own affinity for the natural world. “What was really exciting about working with Morgan is he loved the subject matter. He’s fascinated about evolution and he’s passionate about informing people about the sixth mass extinction that we’re causing. In fact, when he read the final moments of the series, he was really moved by it. It was a special moment, for sure.”

The Earth-shaping extinction events depicted in Life on Our Planet aren’t simply there to provide a neat way of structuring the story—they also serve as a warning. As Freeman and all of the series’ creatives are keen to point out, perhaps the series’ biggest take-home is that there could be another one in our not-so-distant future.

“We hope that the audience will go on this journey and come to a very profound thought at the end: by understanding our past, we can help shape our future,” says Scholey. “After all, the sixth mass extinction that we’re currently living through is the first one created by an animal and also the first one that can be averted completely. The last scene of the series is very provocative and potentially challenging. It will be interesting to see what reaction we get to it. The hope is that when you see the facts as plainly as we present them, the audience will think: let’s do something about this.”

Ultimately, Life on Our Planet is all about hope—and if there’s one thing we know, it’s that life, uh, finds a way.

Life on Our Planet is streaming now on Netflix.