Lennie James interview: Save Me, Storm Damage, The Bill

Sky's excellent Save Me is Lennie James' first TV writing project for almost two decades. He tells us the reason for the long gap...

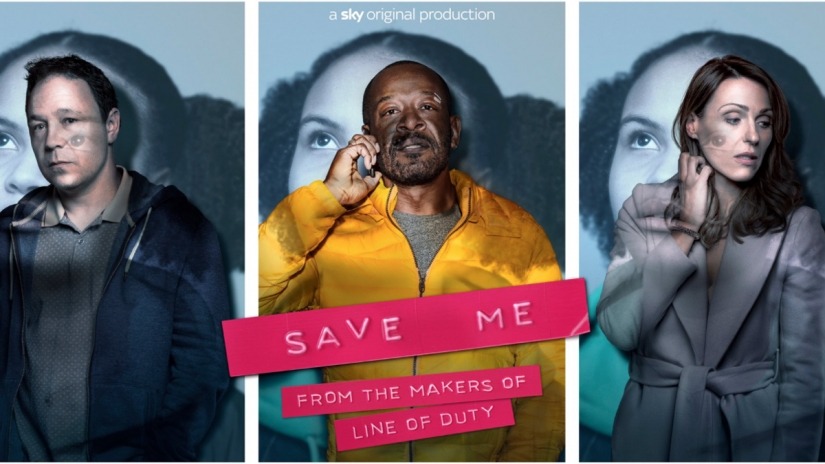

Save Me, a six-part crime series that aired on Sky this spring, is leading the running for drama of the year. Written by and starring Lennie James, it’s an abduction thriller with a difference. Instead of following slick MI5 agents or Met officers on the track of a missing child, we follow James’ character Nelly’s search for her. Jobless and drifting between various addresses and various women, Nelly’s a fixture in his South-East London local and the last person you’d trust to find thirteen-year-old Jody. He has good reason to try though. Despite not being part of her life until now, Nelly is Jody’s dad.

Bolstered by excellent performances from a cast that also includes Stephen Graham, Suranne Jones and Jason Flemyng, Save Me’s script and characters are so accomplished that it doesn’t seem right for it to number among only a handful of writing credits by James. There’s an almost two-decade gap between the first TV film he wrote—Storm Damage, which aired on BBC Two in 2000—and Save Me.

“Yes. Funny that,” says James.

Storm Damage was the story of teacher Danny (Adrian Lester) who returns to work at the London foster home that raised him, where he comes into conflict with teenager Stefan (Top Boy’s Ashley Walters). Danny fails to persuade the boy away from criminality and in the film’s powerful final scene, Stefan is buried after dying from sixteen stab wounds, one for each year of his life.

“That came out of reality,” says James, who like Danny, lived in a care home as a teenager. Storm Damage ends on a powerful monologue delivered by actor T-Bone Wilson as Mister, who addresses the young crowds gathered at Stefan’s funeral. “All of Storm Damage started with that speech,” James tells me. “We did lose a kid. There were one or two hundred young people at his funeral and an older West Indian man, his great uncle, did just start talking to the kids that were there and that’s where all of Storm Damage came from, Mister’s speech at the end.”

In the speech, Mister movingly urges the young mourners to value their lives and not, as Stefan had, to let them go cheap. It’s a message James revisited years later when called upon to write a 2008 piece for The Observer about knife crime. Instead of a feature filled with statistics, as he’d planned on writing, James wrote an open letter to young people about carrying a knife. It’s a blistering piece of writing in which, like Mister, James urges children not to let their lives go cheap.

“The feelings that were in the speech at the end of Storm Damage are the same feelings, unfortunately, that are in the letter I wrote at that time,” says James. What’s really unfortunate, he continues, is that they’re still relevant. Ten years after James’ letter was published, knife crime is still making headlines. “It’s a crying shame that my letter is being read today as if it was written today, but it was written ten years ago, and it’s a testament to how little we’ve done and how little has changed.”

Making Storm Damage wasn’t the experience James had hoped it would be. The project was delayed for several years, and the feeling was that the BBC pigeon-holed it as a specialist race drama rather than the mainstream TV event it deserved to be. Its naturalistic speech patterns were questioned, and James found himself having to spend time and energy repeatedly explaining to and educating “the yes and no people” about their black culture blind spot.

“In a normal thing where you’re writing stuff, you’re always having to explain your vision,” he says, “the difference is that sometimes when the subject turns to race, people get defensive and sometimes that can be tiring and wearing and take up more time than is necessary. You have to find a way of explaining it that doesn’t alienate and it’s a huge amount of effort. I wish that it wasn’t necessary, but it is. It’s a skill that I’ve had to learn.”

Storm Damage was critically lauded, despite its lack of fanfare. Executives hadn’t identified with its mostly black working class characters, so assumed that the audience wouldn’t either. They couldn’t have been more wrong. “The generation of people who were in their late teens or early twenties at the end of the last millennium, if they saw Storm Damage,” says James, “it landed with them.”

One member of that generation is Anne Mensah, now head of drama at Sky. Having seen James’ first TV film when it aired, Mensah put James on a list of people she one day wanted to work with. “I think Anne is of an age where Storm Damage spoke to her generation. She’s from London and knows the neighbourhoods in which I was telling the story.” As Sky’s drama head, she approached him about writing something new, with no idea of whether he had ideas or still had screenwriting ambitions. “She just asked and the question came at the right time,” says James. Save Me is the result.

There had been other writing projects in the almost-two-decades between Save Me and Storm Damage – a couple of plays, a US pilot that “didn’t quite pan out” and an idea for the BBC that was interrupted by what James calls his “American adventure.”

Lennie James’ American adventure is currently splashed over billboards and filling convention halls. After playing the character of Morgan Jones in the 2010 pilot of AMC’s The Walking Dead, James returned to the role in season three, then joined the show as a series regular from seasons five to eight. In a high-profile crossover, he’s just left the parent show to take Morgan to spin-off Fear The Walking Dead. Before and in between there have been roles in multiple TV series and feature films including, recently, Blade Runner 2049.

“You put your head up and you realise it’s been, I don’t know, seventeen years since the last time something that you’d written had been on,” says James, “even if it doesn’t feel like it”. Acting, he’s said, proved “a fantastic distraction” from writing. From now on he doesn’t know which one is going to be distracting from the other, “but they are very much going to be co-existing. I want to be ready for that double-headed beast.”

As might be becoming clear from James’ experience with Storm Damage, his American adventure isn’t the sole explanation for the long gap in writing.

“I can look back and say now that I wasn’t aware that it was going on, but one of the downsides is that in the aftermath of Storm Damage, some of the ideas I had and some of the things I thought I wanted to write about, I allowed myself to be talked out of, or talked myself out of because I was aware of what the struggle would be to get that made. That is unforgiveable. But that is one of the by-products of it. Subsequently, now that I’m a bit more grown, I realise that I’m not prepared to have my ideas or the stories I want to tell be limited by other people’s ability to understand.”

Thirty years ago, James’ first real taste of screenwriting was soured by more ignorance. In 1990, two years after graduating from drama school, he landed a job writing an episode of ITV crime series The Bill. The story was about an old friend from DCI Burnside’s past, Papa Reeve (played by EastEnders’ Rudolph Walker) whose son sought Burnside’s help in stopping his dad from euthanising his terminally ill mother.

The Bill’s half-hour format had given it a reputation as a good training ground for young writers. That was far from James’ experience. “In all honesty, it wasn’t pleasant at all,” he says. “There was an immense amount of pressure on me that now, looking back on it I just think was kind of unforgiveable. They overly focused on me as being a black writer as opposed to a writer. They were clumsy, they were awkward, they were ignorant and they made big mistakes.”

James was the first black writer in The Bill’s then six-year history to have an episode made. “I said, really? They should really be ashamed of themselves, considering how many black actors they’d used.” Black actors, it’s worth noting, who weren’t wearing Sun Hill police uniforms, but were repeatedly chased and banged up by those who were.

Seeking to capitalise on the good publicity of hiring James as The Bill’s first writer of colour, he was asked to pose for stills for a press release. “I went down to set to take a photograph and when the photograph appeared in the paper it was headlined as the character of Burnside arresting me as opposed to it being used as publicity for me as the first black writer.” He’s incredulous recollecting the story. “They messed up on a number of levels. They didn’t really help me as a young writer, they seemed more frightened of me than wanting to nurture me and that was unfortunate. I hope and pray that for young writers of colour coming through now that things have changed because The Bill was not a good experience.”

James didn’t write any further episodes for the show. “I very firmly told them to shove it”.

On the subject of nurturing young writers of colour, when asked, incidentally, whom he would recommend to work on one of the Save Me episode scripts that his commitments to The Walking Dead didn’t allow him enough time for, James pushed for Marlon Smith and Daniel Fajesmisin-Duncan, two writers on whose Channel 4 drama Run he’d worked in 2013. “Run was one of my favourite jobs of all time,” he says. “Marlon and Daniel were my first choices and they will also be writing on the second series as well.”

James found his own nurturing as a writer and actor from individuals, not institutions. First, from filmmaker Horace Ové, who gave James his first major TV role out of drama school in 1991’s The Orchid House.

“One of the major influences on my career and life, it’s Horace,” says James. “He’s very much one of the giants on whose shoulders I’ve been lucky enough to stand upon.” James describes Ové as a “kind of surrogate dad and mentor and touchstone for what must be the vast majority of my career.”

When James wrote Storm Damage, Ové sat with him and gave “sage and good advice,” he remembers. “I asked him what I needed to do and how to handle it. He watched things that I did and would send messages and notes and criticisms and remind me of myself and the way that we do the job.”

“It’s one of the things that matters most,” says James, “what does Horace think of it?” What did Horace think of Save Me, I ask. “He can’t communicate in the way that he used to communicate but I got a message from Indra, his daughter, that he was aware of it and really liked it.”

Other writing influences James cites are Alan Bleasdale, Dennis Potter, Walter Mosley, Toni Morrison Steven Bochcho (“Any television show you can mention as being good or great or seminal, you can trace it back to Hill Street Blues”), and Lynda La Plante.

“Lynda also was an actress who became a writer for much the same reasons I did, which is about trying to tell stories that you felt weren’t being told.” First cast in Civvies, La Plante next sought James out for a part in her two-part crime drama Comics. “I count that as one of the major stepping stones in my career. When I went in the room after Comics, there was a different vibe than when I went in before Comics. She showed a real loyalty to me and was there both as a storyteller and as someone who championed me as an actor and I’ll be forever grateful to her.”

When it comes to seeking notes on his own writing, James perishes the thought of consulting the many screenwriters he’s worked with as an actor. “No!,” he laughs. “I’m very secretive.” What about Jed Mercurio, in whose work James has played the lead twice, first in Line Of Duty series one, then in Sky medical drama Critical?

“Would I send it to Jed? No! He’d give me his opinion! No! Jed frightens me!” he laughs. When it came to Save Me’s first screening, Mercurio’s opinion, says James, “was one that I was most apprehensive about because he doesn’t pull his punches, Jed. He’s also a very bad liar so if he didn’t like it, even if he’s saying he did like it, you’d know.”

So, did he like it? “He let me know straight away that he genuinely liked it and…” James chooses his words carefully, “was a little bit impressed.” Among all the praise James has received for Save Me, that was one of the most gratifying verdicts. “In my opinion, Jed is the most accomplished TV writer I think I’ve ever come across, apart from possibly Lynda La Plante. He knows how to tell a television story unlike any other human being. I think he’s probably the guy at the top of his game. For him to be genuinely impressed by the job I did on Save Me meant the world.”

Mercurio wasn’t the only one impressed by the job James did. The cast Save Me attracted speaks for itself. As an actor, he tells me, he knew what kind of script would make actors “salivate”, he laughs. His approach was to write parts that weren’t “just cyphers for telling the story. Particularly in the characters that inhabited the estate and the pub, it was really important that you got some sense of their life outside the story, that they weren’t just there for their role in the telling of the bigger story of the finding of Jody, but you had some sense of their history and life that we weren’t seeing yet.”

The approach paid off, and created what James is proud to call, “an environment where people were happy to work their arses off!” Thanks to the ensemble’s talent, says James, Save Me was able to negotiate some tricky boundaries. “Because of the nature of the people I was writing about, we’re always just slightly navigating inches either way from stereotype and kind of a pastiche of East-enders, as far as television audiences perceive. There was a line that we needed to tread very carefully and that was in the main achieved by the abilities of the actors.”

His ultimate goal in Save Me, which has already been renewed for a second series, was not to write “television about television,” he tells me. The modern TV audience, he says, “is really informed and expectant. They’ve become au fait with the patterns of storytelling.” Without revealing anything about Save Me’s plot, James wanted to subvert those patterns and swerve in unexpected directions.

“I didn’t want to write it based on what you see on television,” he explains, “I wanted to write it based on a part of London that I was familiar with and populated by characters I knew, and trying to put a thriller on top of that. There were certain tropes of the thriller that you’re forced to adhere to, but I didn’t want that to adversely affect a story set in a real place, populated by real people that I was trying to portray.”

Most important of all, he tells me, was that he and director Nick Murphy reveal the beauty of the place and people that tell Save Me’s story. “If you talked to most people about writing a story about an estate in South-East London, all the hardships and the difficulties and the dole and the violence and the aimlessness… all of that is present but it isn’t the only thing that goes on there. The other thing that goes on there is people raise their families. People laugh. People dance and there is beauty there and there are lives of worth there. That’s what I wanted to write about.”

Save Me season 1 arrives on DVD on Monday the 7th of May 2018 and is available to pre-order now.