Zak Penn interview: Ready Player One, positive and negative fandom

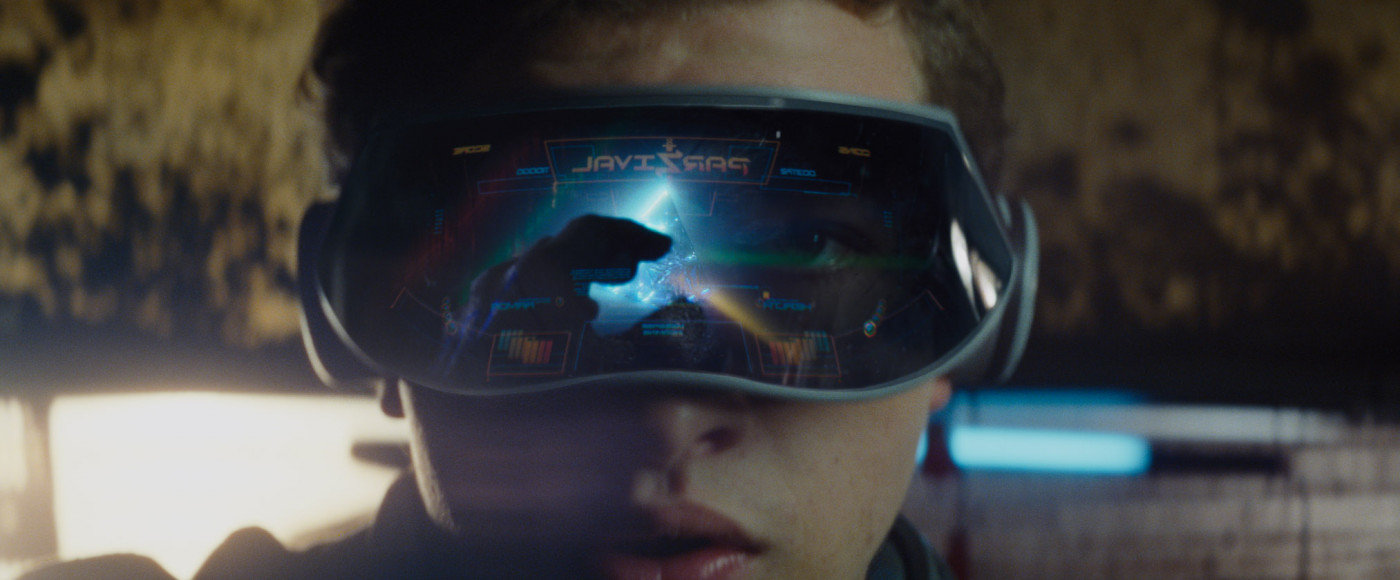

What does Ready Player One say about toxic fandom? Can we love geek culture too much? We talk to screenwriter Zak Penn to find out...

The last time we spoke to screenwriter Zak Penn, he’d just finished Atari: Game Over, a documentary about the collapse of videogame company Atari and one of the industry’s great urban legends: that huge quantities of unsold E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial games were buried in a New Mexico landfill. (A legend that turned out to be partially true.)

That’s the kind of geek history that would fit perfectly in Ready Player One, Ernest Cline’s best-selling novel steeped in 80s pop trivia and nerd culture. And, in a strange twist of fate, it was during the making of Atari: Game Over that Penn began to figure out how to go about the incredibly complex task of adapting Cline’s book – all about an easter egg hunt in a virtual world – into a movie.

That movie, directed by Steven Spielberg, arrives on Blu-ray on the 6th August, marking the culmination of a lengthy development process that began right back in 2010. Rights to the book were being auctioned before it was even published, and by the time Zak Penn began writing the screenplay in 2014, there were still more hurdles to clear – not least the lengthy rights clearances for all those pop culture references.

Together, though, Spielberg and Penn highlight the faintly melancholy strand that runs through the original book: that of an ageing game designer looking back over his life and its missed opportunities. As well as a reference-filled easter egg hunt, then, Ready Player One is also a cautionary tale about our modern relationship with geek culture (“Love it, but don’t love it too much,” seems to be Halliday’s message).

With Ready Player One’s home release on the horizon, then, we caught up with Penn on the phone to talk about the process of adaptation, and what the film might say about the current state of fandom.

How does it feel, now that the dust has settled on Ready Player One a little bit? Because it seems to me that the development process on this film was quite long.

Yeah, it was about four years. Which ironically for a movie, a lot of them take longer than that to get made. Not in terms of production – it was a long term in production, certainly, because it was half animated and half live-action. It feels good, you know? I miss it a little bit. It was a lot of fun to work on, and I miss the day-to-day of it.

It was weird to go to work every day and see something cool and new. To feel like there’s a hundred people working on the script at the same time I was – that was a good feeling. Sometimes I wish that were the case today, with the thing I’m working on.

But I feel really good about it – I mean, I have a lot feedback from people who’ve seen it and are excited to see it on Blu-ray. I have nothing to complain about. I used to be a good interviewee because I had lots to complain about! And now I don’t, so I’ll have to keep it interesting somehow.

I know there was a draft of the script written before Steven Spielberg was attached, so how did it change when he came aboard, and what did he bring to the writing?

Well, he brought a lot to it. Number one, he brought a far more intricate level of cutting between [the real world and the virtual]. Even on the page, he had a concept in mind of how often we were going to cut back and forth from the real world to the Oasis. In the script, it’s not fully addressed, because there’s no need to – you don’t know how often you’re going to do it. But he really wanted to establish this physical link between what people are doing in the real world and what’s happening in the Oasis, and not just for exposition reasons. He has a lyrical quality in mind, and that became a lot of what we did.

The structure of the book had already changed for the movie – it was like going through every sequence and really drilling down into it and figuring out how we relate what’s going on in the real world with what’s happening in the Oasis. And also, decreasing the time the story takes place over; [Spielberg] definitely challenges himself by doing things like that. [In the book] it takes place over the course of a month, but now it takes place over the course of a week, so let’s make that work.

I guess, for both of you, it’s a case of taking a piece of writing and making it visual and cinematic.

Yeah. And look, there were some things had changed before. Like, the Halliday journals was something I’d pitched to Ernie before I even wrote it. I just said, this is my plan. There’s a great opportunity here – in the book, you can just describe scenes that happen, and you don’t have to explain, but in the movie, we’re going to want to see the actors.

We aren’t going to want Wade reading about this in a book, so the Halliday journals became an actual archive where you could see the scenes [from Halliday’s life]. That was a big change, but it seemed necessary to me. Because otherwise you’d barely ever see [the characters]. I don’t know where you’d see Morrow. You’d just have a glimpse of him here and there. So that’s one example.

Making the challenges more visual and a lot less text-based – that was not a controversial [approach]. Ernie was saying the same thing – he was pitching stuff to me before I even came up with stuff myself. You always figure, if the author of the book is telling you, please change this, then you have licence to change it.

What you’ve done with Halliday’s really interesting. He becomes a quite immediate character in the film, I thought, and slightly melancholy, too – a lot of the games he creates for the players are more obviously rooted in his regrets.

Yeah, definitely. And look, I pushed in that direction, but so did Steven, and there’s a lot of Steven’s relationships with his own friends that Ernie was calling on anyway. But I think through the actor and the director and so many other people, the part evolved. As a writer, you have to give them a pathway. I said in the first draft, this has got to be about Halliday – and some of this is in the book, by the way, just in a different order – but it’s got to be about Halliday confronting what he did wrong.

It can’t just be, he didn’t kiss a girl. That’s not enough. It’s fine that he thinks that’s what he did wrong, but that can’t be the deeper meaning there. There’s gotta be some insight that Halliday gained that he’s trying to impart – that’s what really does set him apart from Willy Wonka – this is a guy who’s already dead, who’s trying to find someone to take over for him, and he’s a game builder. So I tried to take all that and say, okay, well how is this not a bad idea?

That was one of the things that was helpful about it. The scene where Sorento points out, “This is a terrible idea” – he has this huge company that’s super-important to a lot of people, and he’s created a game to figure out who to run it next. So I tried to go from that and make Sorento right in his own mind, but then have the contest also be something that says, no, a lot more thought went into this, and Halliday had a lot more regrets than he let on. That was a really helpful way to look at it for me.

Yeah, yeah. Do you think that adds a slight cautionary message to the film? To love pop culture, but not get completely lost in it?

Oh, absolutely. It’s funny. Ernie said something to me: I did a documentary, Atari: Game Over, and Ernie’s in it. That’s partly where we became friends. I got hired to write the script while I was making that documentary. And one of the things he said to me – he says it on camera – is, “I love things, and I love people who love things.” And when he elaborated, he meant, he doesn’t just love stuff for the sake of it, he loves it because it brings him together with other people who love it. He doesn’t sit in his room counting up his action figures and playing with them by himself – and the people he’s writing about are the same way.

If your obsession drives you away from people, then it’s probably not healthy. But if the things you’re interested in draw you to other people and connect you to them, that’s great, that’s what life is supposed to be about. In the same way, if your kid was playing chess all day, and then going out to chess club, the parent wouldn’t be like, “Oh my god, this thing’s going to rot your brain. Stop playing chess!” You know? Or, “Stop playing guitar. Stop playing basketball.”

They would never say that. But by the same token, if you’re really fascinated by something in pop culture, to the point that it causes you to dig down deep and study it, and talk to other people about it, that’s great. If you turn into a lonely jerk about it, then it’s not good at all, you know? If you become obsessed about it to the point where you become religious about it, then you kind of miss the point.

That’s timely as well, isn’t it? Because there’s a lot of discussion right now about positive fan culture versus toxic fan culture.

Yeah. And I don’t mind if fans are critical. I think it’s perfectly reasonable, and as a fan, I can be very critical of things I don’t like. But there’s a difference between taking personal offence at what the people working on those projects have done, or seeing it as some sort of betrayal – that, clearly, is the toxic part. So, you know, people sometimes say, “Oh, so I’m not allowed to criticise?” And I say, “Yeah, you are allowed to criticise! In fact, criticism is encouraged.”

Everybody who is a fan is going to be critical of some of the choices. But if you try to negate what’s been done… first of all, you have to acknowledge the fans. There’s someone who hates everything, in every moment. Particularly in comic book movies, this is less true on Ready Player One, but in comic book movies, people are like, “It has to be this way. This is the way I loved it.” And you want to say to them, “Do you realise there are a bunch of people who hate that, and if we do it that way, those people will say they hate that version?”

You know what I mean? You can’t make any piece of writing or art [appeal to everyone]. You just can’t do it that way. So what you end up with is nothing; if you do the union of everybody’s notes, there literally won’t be a line left. That’s something that needs to be addressed – or something people have to be aware of, the fans. They have to have some self-awareness. “Okay, this was not canon that was delivered by god on stone tablets”. It’s a fluid piece of art, and it should be treated as such.

In that regard, were there things that you as a writer wanted to get in the script but couldn’t for whatever reason?

There were lots of things in the book that we couldn’t get the rights to for legal reasons. Ultraman was one – there was a lawsuit over it. Fans were, like, how can you do this? But I was, “What do you mean? There’s a lawsuit over it. We couldn’t get the rights. It would’ve prevented the movie from being released. Is that the version you’d prefer?”

But also, not everything works in cinema as well as it works on paper. There wasn’t a lot. The kinds of things that didn’t make it in were, we did a scene with, like, a throwaway reference to this that or the other, and that scene got cut, so there’s no longer a reference to it. But I can tell you, I’m not the type of person, after all these years working on all these movies, there aren’t that many references left that I’m desperate to see on screen. You know what I’m saying?

There was a time when I got to Hollywood where there were all these comic book characters, and the whole Marvel universe wasn’t on screen. I couldn’t wait until the day when I got to see these characters live and breathe. But with Ready Player One, what’s funny is, it’s not those actual characters [you’re seeing in the movie].

Some people say, “It’s good to see the Iron Giant again.” But really, it might be the Iron Giant visually, but that’s not the Iron Giant – that’s someone wearing an Iron Giant outfit. So it’s not really fanservice in a lot of ways. Fans will say, “This isn’t the way Batman would do things.” But we’re saying, “Wait, that’s not Batman.” You know? When you go to Comic-Con, the guy dressed as Batman isn’t really Batman! He’s just dressed up that way.

That’s an interesting point, actually, about what Ready Player One really represents: it’s that modern version fan culture that’s interactive. Where you have conventions and cosplay. When I was a very young nerd, cosplay simply didn’t exist.

You’re right, it was the same with me. And right, that’s the thing. It’s weird how much on the internet and on Twitter, how much time… particularly people who were critical of the [Ready Player One] book. How much time they wasted complaining about it: “Oh my god. References: The Movie – that’s what it’s gonna be”.

And you just want to say, “Do you think that’s what Steven Spielberg’s gonna do? Do you really think that’s what the book even is? The book has a story. The story is not about its references – the references are part of Ernie’s style, but the story’s about a kid who lives in a horrible, crappy slum-like building who figures out how to solve the biggest puzzle in the world. He meets his friends, and together, they do it.” I think that’s the story.

One final question to wrap up, then. It struck me how Wade Watts looks like a young Steven Spielberg in this film. Was that something that ever came up in discussions?

Uh, I think that’s very unintentional. I hope he won’t get angry with me for saying this, but I’m sure he won’t: Wade and Tye [Sheridan] are very different ethnically and in a lot of ways. Although I have to admit, he’s the character he associates with the most, but I don’t think it was an intentional homage to himself.

But it’s an interesting idea! You’re free to interpret it as you will. Maybe he did. I have my own opinions about who each of the characters represent in his own group of friends: which one’s [George] Lucas, which one’s him, which one’s whoever. But he wouldn’t agree with me, nor would he confirm, I’m sure.

Zak Penn, thank you very much.

Ready Player One is out on digital on the 23rd July and 4K, Blu-ray 3D, Blu-ray and DVD from the 6th August.