The Real History of The King’s Man

We examine the real history that informs more of Matthew Vaughn’s The King’s Man than you might expect.

This article contains The King’s Man spoilers.

Matthew Vaughn’s The King’s Man is on streaming now. That’s a quick turnaround since its Christmastime release last year, but perhaps it’s for the best. With the largely underappreciated (and under-seen) Kingsman prequel making its debut on HBO Max and Hulu, there’s a chance the strange action mash-up may finally find its audience.

Indeed, the film’s pitch always seemed a bit niche, even for this franchise. By eschewing the modern class conflict of the first two Kingsman movies, which created a dynamic of “street” versus posh spy, the World War I-set The King’s Man travels back in time more than a hundred years to tell a story that has more in common with Rudyard Kipling novels than Ian Fleming. The King’s Man is about the last gasps of the Empire, and a global conflict that destroyed the 19th century world order, including British dominance.

In fact, The King’s Man is so steeped in World War I history that the truth behind many of its larger-than-life characters and story beats could surprise casual audiences. So below we’ve gathered some of the basic facts that Vaughn’s action romp touches on in its stuffed, breakneck two-plus hour running time.

The Assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand

As hopefully anyone who’s completed a grade school education should know, the First World War was, indeed, triggered by the death of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria and his wife Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg. The King’s Man dramatizes this in a jolly and almost incredulous fashion with the archduke and his wife (Ron Cook and Barbara Brennan) apparently starring in an action-comedy as they joyride around Sarajevo alongside protagonists Lord Orlando Oxford (Ralph Fiennes) and his son Conrad (Harris Dickinson). It’s played even for a dark chuckle when the royals’ assassin, Gavrilo Princip (Joel Basman), is having a nice little coffee at an open door cafe and sees the royal procession drive past him and make a wrong turn. He then kills them as they reverse out of a three-point turn.

The scary thing is that a global conflict that left tens of millions dead really did start with an assassination this hapless.

The real Ferdinand was the heir apparent to an Austro-Hungarian throne that was never meant to be his. Franz was born the son of Archduke Karl Ludwig of Austria, the current emperor’s younger brother. After the emperor’s own son died, as well as Franz’s father, the unliked nephew became heir-apparent—much to the disdain of his family’s court since he soon married Sophie Chotek, a lady-in-waiting who was considered to be too inferior of birth for the throne. To keep their power, Franz and Sophie even had to renounce their then-unborn children’s claim on it.

When the couple arrived in Sarajevo in June 1914, the region was a hotbed of political unrest. Bosnia had been under the rule of the Austro-Hungarian empire since 1878 and had ever since been an occupied province within the empire. Hence the Young Bosnia political movement, of which Franz and Sophie’s assassin was a member. In reality, Princip was not a mature adult (or member of a secret anti-Britain cult); he was a 19-year-old Bosnian-Serb student and a separatist who believed in the need to reunify Serbia. The young men who made up Young Bosnia were so confident in these political aspirations that an entire group of them planned the assassination of the heir to the Austrian throne when he came to down.

The scene in the movie where a grenade goes off beneath the car behind the Archduke’s vehicle? That really happened, although it was not a lone-acting Princip who threw the bomb, nor was there a dashing proto-Kingsman there to swat it away an umbrella. Rather a different young Serb named Nedelijko Cabrinovic threw the grenade and it failed to detonate until underneath the second car. (Another assassin who was supposed to shoot them in case this plan failed lost his nerve and walked away elsewhere in the city.)

The archduke was incensed by the attack, and he and his wife agreed to visit the hospital where those injured by the bomb were being treated. This change in itinerary caused a confused driver to miss his turn, precipitating the need to reverse. As he did so, Princip really was sitting across the street at a cafe drinking a cup of coffee and regretting missed opportunities. When he saw the royal couple in a stalled car a few feet away from him, he got up the nerve, walked across the street, and murdered them on the spot. The assassinations triggered a political firestorm which eventually resulted in World War I.

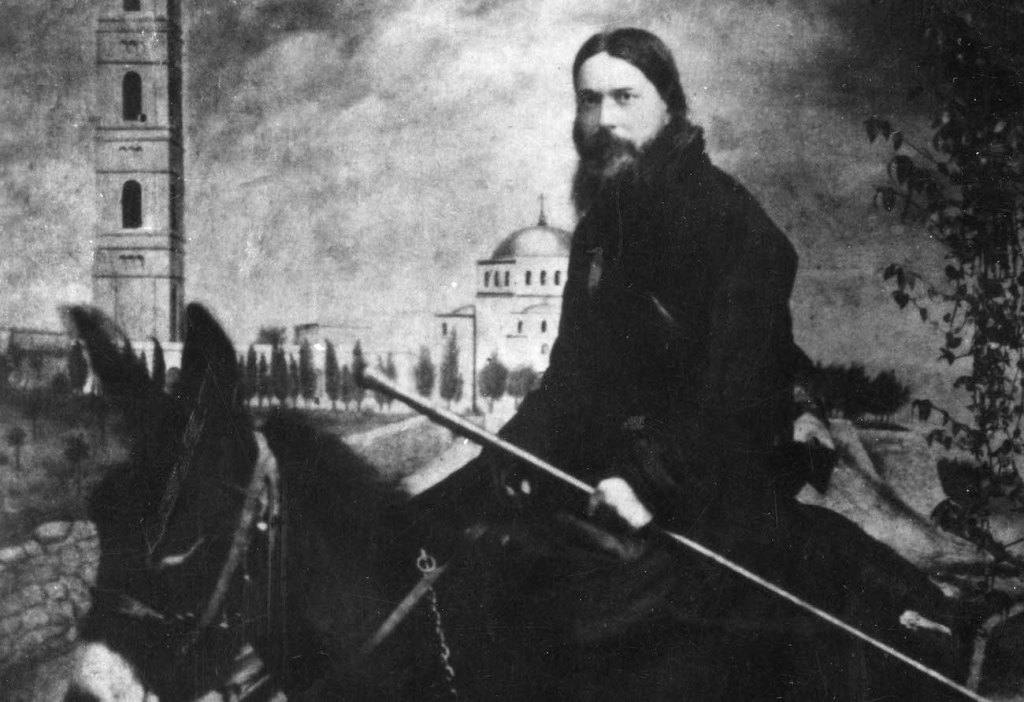

The Death of Rasputin

Was Grigori Rasputin really a magical holy man with the ability to heal permanent injuries and war wounds? Unlikely. But the truth of Rasputin’s life has long been obscured by rumor, innuendo, and legend, much of his own making. At the very least, it’s known he was born as a peasant in the Siberian village of Pokrovskoye in 1869. His alleged religious conversion did not occur until 1897 upon visiting a monastery, however this “monk” was never an actual member of the Russian Orthodox Church. In fact, as his influence first began to grow in the imperial court, local clergy from his hometown denounced Rasputin as a heretic.

But by that time, the boorish yet charismatic grifter had long succeeded at convincing wealthy nobles in St. Petersburg of his mystical healing powers. It’s there Rasputin first met Tsar Peter Nicholas II in 1905. The Russian emperor was in a desperate state due to the sickness of his son Alexei, who suffered from hemophilia. Rasputin convinced the tsar and tsarina of his ability to heal the child’s ailments. He was quickly hired as the royal lamplighter but soon became a kind of advisor and confidant to the tsar. Some even feared the royal family’s puppet master.

With his crude behavior and strong influence over the emperor, Rasputin became increasingly unpopular at court, particularly after the First World War broke out. There are some rumors that Rasputin participated in gay or bisexual orgies, but many of those cropped up after his death. In his lifetime, his enemies were known to more loudly whisper stories of blanket hedonism, some dubious (that he was sleeping with the empress and her teenage daughters), and others sadly more likely true (sexual coercion and even rape of his female followers).

Hence multiple assassination attempts. The first came in 1914 when a peasant woman, on the likely suggestion of an Othodox priest, stabbed Rasputin in the stomach. He survived.

The successful assassination which is turned into a grand action sequence in The King’s Man did not involve British spies or, as far as we know, elaborately choreographed Cossack dance-fighting. However, not much is actually known about what occurred the night of Dec. 16, 1916 other than Rasputin was ultimately shot three times, including finally in the forehead, by a conspiracy of conservative Russian nobles (who some historians suggest were gay themselves). These men were determined to divorce Rasputin from his hypnotic-like influence over the tsar.

… However, Prince Felix Yusupov, who masterminded the assassination plot, wrote in his memoirs a pretty salacious account of the murder that to this day clearly makes for a great story. According to the prince, they lured Rasputin into a stately holiday dinner and fed him teas and cakes laced with cyanide… which did nothing. They then gave him Madeira wine laced with more poison… which also did nothing. Finally the prince left, retrieved a revolver, and came back down the stairs to shoot Rasputin twice in the chest. Later that night, Rasputin allegedly rose from his seeming death to attack the prince and try to strangle him, eventually chasing him out into the courtyard where he was shot once again, this time in the forehead. Good and dead now, Rasputin’s body was carried by the noble conspirators through the snow to a bridge over the Malaya Never River. There, they dropped him into the icy water.

So there may not have been high kicks, but that’s still a pretty spectacular exit!

The Zimmerman Telegram to Mexico

In a kernel of history that seems evermore incredulous to modern eyes, Germany did attempt to persuade Mexico into declaring war on the United States in 1917—a folly that would eventually become the final straw before the U.S. entered the First World War.

The motivations behind German Foreign Secretary Arthur Zimmermann’s fateful cable are complicated. Essentially, the German High Command believed war with America was inevitable in 1917 since the German submarine strategy would return to total warfare by late February in the North Atlantic, sinking as many American merchant vessels as possible in the hopes of preventing supplies reaching Britain and France. So the German government strategized that if they preemptively could distract the U.S. in a war with its border neighbor Mexico, the German military could win the perpetually stalemated war along the Western Front before the U.S. would have time to train and mobilize soldiers to aid their European allies conceivably a year or more down the line.

The infamous letter in question, “the Zimmerman Telegram,” offered to help Mexico reclaim the lost territories of Texas, Arizona, and New Mexico for this bloody action.

“We make Mexico a proposal of alliance on the following basis,” wrote Zimmerman. “Make war together, make peace together, generous financial support and an understanding on our part that Mexico is to reconquer the lost territory in Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona.”

Unfortunately for the Germans, the communication was intercepted by British codebreakers—as seen in the movie—in what is considered the most successful act of espionage by the British in WWI. The cable was then shared with President Woodrow Wilson, who still dithered because he campaigned as an anti-war president and allegedly because he did not want to publicly reveal that the British had broken the Germans’ code.

By March, Zimmerman personally removed that latter impediment by publicly admitting he wrote the cable first in an interview and then in a speech. His public admission operated still under the belief that this would be a deterrent for the U.S. to enter the war in aid of the British. Instead it gave enough political cover for Wilson and the U.S. Senate to declare war.

For Mexico’s part, President Venustiano Carranza at least entertained the idea of allying with the Germans. Relations with the Americans were already frosty after the U.S. sent in a paramilitary force across the border to root out Carranza’s own enemy, the revolutionary Pancho Villa, who had made encroachments onto American soil. But because of that ongoing civil war that Villa personified, Carranza’s own generals concluded in a commission report that going to war with the U.S. was too risky in such an untenable situation. Any second guesses on Carranza’s part became mooted when Zimmerman confirmed the cable was real in March, and Mexico officially declined the invitation.

Mata Hari the Spy

Mata Hari was probably the most famous spy out of the First World War—although she might not have been a spy. (At least of the German variety.) Despite being depicted as a cunning temptress who seduced no less than Woodrow Wilson in The King’s Man, she never actually made it Stateside during the war.

Prior to the war though, she developed an international reputation as the great exotic dancer and toast of turn of the century Paris. Despite her Indonesian title, she was actually born into a Dutch family as Margaretha Geertruida Zelle in 1876. Her public persona was said to be a Far East princess, but in truth her father was a small businessman in the Netherlands. However, she picked up a strong fascination in Southeast Asian culture after marrying a Dutch colonial army captain and following him from Amsterdam to the Dutch East Indies in the 1890s. Their marriage was an unhappy one, with the husband carrying out torrid affairs and picking up syphilis (which killed their children), but she developed an affection for the local culture, including by adopting the name Mata Hari, which is Malay for “eye of the day,” the term used to describe the sun.

After returning to Amsterdam, Zelle divorced her husband and soon moved to Paris where she became the famous Mata Hari, renowned for apparently turning the act of striptease into an art-form. While some critics looked down on her, her popularity was so great that by the time she felt she aged out of professional dance in the 1910s, she still had success as a courtesan with a Bohemian reputation, keeping lovers in multiple governments, industries, and militaries.

It was her apparently passionate relationship with a Russian pilot who flew for the French that first attracted the interest of the French secret service, the Deuxieme Bureau. The Duexieme knew the famed Hari had at one time had an affair with the Crown Prince Wilhelm, heir to Kaiser Wilhelm II’s throne in Germany. Unfortunately for French espionage, Prince Wilhelm was considered feckless and only had a nominal title in the German military. Even so, the Deuxieme offered Hari one million francs if she could visit her injured Russian lover—who had been shot down and became a prisoner of war in Germany. Given her celebrity status, and her passport belonging to a neutral nation like the Netherlands, it was assumed she could enter Germany.

Hari agreed and traveled to Germany where she also took money from the German military in trade for state secrets. It is debated whether she actually did this as an act of betrayal or if she simply was trying to garner German trust in order to gain an audience with the crown prince. Indeed, German military officers grew skeptical of her since she traded with them only gossip of a sexual nature about French politicians. In a cable that nakedly implicated Hari in all but name as a German spy, the Germans even used a code they already knew the French had broken. If the plan was to falsely frame her as a German double agent, it worked. The French assumed Hari had turned double agent on them. And, in a year where catastrophic military losses were further breaking public morale, the government seized on Hari as a potential scapegoat, blaming her for the deaths of 50,000 soldiers.

When Hari returned to Paris in 1917 she was arrested and tried for treason. “A harlot? Yes,” she is reported to have said at the trial. “But a traitoress, never!”

On Oct. 15, 1917, Hari was marched in front of a firing squad of 12 French soldiers. She declined a blindfold and blew the soldiers a kiss. They then shot her. She was 41.

The Death of the Imperial Romanov Family

Tsar Nicholas II of the Romanov Dynasty abdicated his Russian throne in March 1917, following the February Revolution, the first of two revolutions in Russia that year that transformed the country from a feudal state into a communist one under Soviet rule. Nicholas initially abdicated his throne, as well that of his sickly son Alexei, in hopes of making his brother Grand Duke Michael the emperor. That plan did not last.

By July 1918, Nicholas and his large family were under house arrest in Yekaterinburg. And in wee small hours of the morning on July 17, they were brutally slaughtered by Bolshevik revolutionaries. The popular myth is that they were told they were having a picture taken when the photographer instead shot them—a fantasy dramatized in The King’s Man, including, bizarrely, with the reveal that Adolf Hitler was the executioner. The reality was grimmer.

Around two in the morning on July 17, the royal family was awakened and told to get dressed in their finery and go hide in the basement of their Ipatiev house. They had been told this was to protect them from supposed anti-Bolshevik forces gathering in the region. In actuality, Bolshevik officer Yakov Yurovsky had ordered their executions. When the whole family was gathered, Yrovsky even honored a request by the former emperor to provide two chairs, one for his wife Alexandria and one for a daughter. Among the children were Olga, Tatiana, Maria, Anastasia, and Alexei, the youngest and sickly child being carried in his fathers arms. The daughters were between 17 and 21 years old.

The executioners filed into the room, and Yurovsky announced that the Ural Soviet of Workers’ Deputies had ordered their execution. The emperor’s last words were reportedly, “What? What did you say?” The firing squad emptied handguns into the family. Yet only Nicholas, his wife, and his son reportedly died in the immediate volley. The daughters had been shielded from fatal shots by their jewelry. So the executioners approached with bayonets and gutted the teenagers to death.

Their bodies, as well as those of their most loyal servants who were also executed that night, were thrown down a mineshaft that was then sealed. Its location was hidden from the public and history until the Soviet Union’s collapse in the 1990s. Other members of the royal family, including the tsarina’s sister, Elisabeth, arguably fared worse when she and her family were essentially buried alive by being thrown as prisoners into another mineshaft.

The Bolshevik government successfully exited the First World War before these executions. The rising Soviet government promised a fairer system and justice for its citizens. It did not happen.