The Pale Blue Eye Explores How Edgar Allan Poe Was Author of the First Detective Story

Christian Bale’s eccentric constable has deep roots in Edgar Allan Poe’s seminal sleuth, and The Pale Blue Eye misses nothing.

This article contains minor The Pale Blue Eye spoilers.

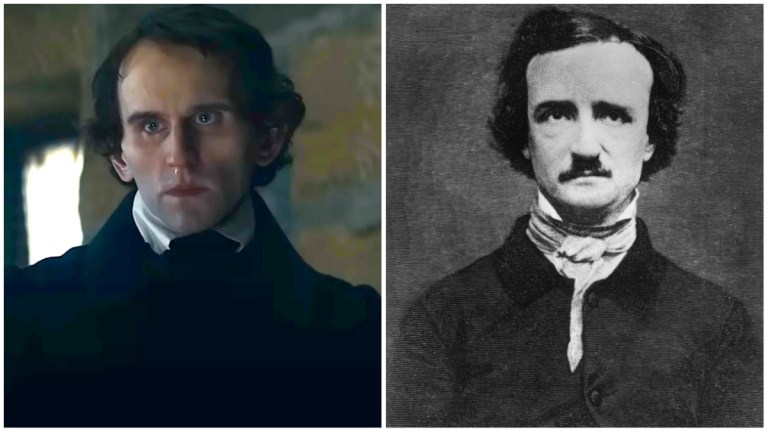

Based on a novel by Louis Bayard and not true events, director Scott Cooper’s period thriller The Pale Blue Eye imagines a young Edgar Allan Poe, as played by Harry Melling, in the short handful of months he attended West Point Academy as a cadet. By this time, Poe had already published two books of poetry and served in the U.S. Army before matriculating at the military school on the Hudson River. He had not yet invented the detective mystery genre with “The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” published in Graham’s Magazine in 1841. Hence the film offers a theoretical scenario for its inspiration: The tortuous murder, and grisly desecration, of Cadet Leroy Fry (Matt Heim) is committed on the school’s periphery, and a killer is at large.

The Pale Blue Eye stars Christian Bale as retired constable Augustus Landor, who enlists Poe to help chase leads as the perverse murder case brushes against the fringes of occult complicity. Like breadcrumbs for a raven, scattered clues lay a labyrinthine trail through the themes of Poe’s works: gross morbidity, premature death, and supernatural promise. The film is the coming-of-age story of a budding mystery author destined to rewrite the rules. Bale’s Landor comes to the aid of West Point Academy to save its reputation in spite of his own revulsion at their regulated restrictions. He believes such established methods systematically rob young men of individual thought and openly proclaims his aversion to the academy’s rules. He prefers unfettered analysis, just like the father of the detective mystery.

Augustus Landor is a fictional creation from Bayard’s novel and now Cooper’s movie. His last name comes from Poe’s short story, “Landor’s Cottage.” Originally published in 1849, it is a descriptive work, without mystery or violence, that works as a contemplative rest stop for the retired detective’s dwelling in The Pale Blue Eye. The rustic home, designed after the one in the book, marks him as a recluse, and he is derisively called a “cottager” in the film by a prime suspect in a secondary role.

The Birth of a Genre

While his surname may come from “Landor’s Cottage,” The Pale Blue Eye’s main character being named Augustus is a direct tribute to Poe’s most famous criminal investigator, the central figure in the trilogy which makes up the first detective series. C. Auguste Dupin is the master analyst in Poe’s “The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” “The Mystery of Marie Rogêt,” which was published in three installments in Snowden’s Ladies’ Companion, beginning in late 1842, and “The Purloined Letter,” published in 1844.

Poe the writer is renowned for macabre tales and anguished poetry, but he’s also exalted for his contribution to the mystery genre. The Edgars, the most prestigious award of the Mystery Writers of America, is named in his honor. Poe’s use of rational crime-solving created a genre, not only mixing a detective narrative that revolves around figuring out “whodunit,” but inviting readers to put the clues together.

Poe called these armchair challenges “tales of ratiocination,” combining scientific reasoning with intuition far superior to the incompetent constables’ haphazard application of trial and error derisively mocked in the short stories. Dupin’s investigative process allows for intuition resistant to traditional institutionalized police work. Cops are an annoyance who only get in the way in these stories. Arthur Conan Doyle would lodge similar complaints 46 years later in his Sherlock Holmes series against Inspector Lestrade and Scotland Yard.

The Mysteries of the Morgue Manifested Many Firsts

Poe’s C. Auguste Dupin trilogy contributed multiple unique introductions to literature, the specific genre, and popular culture. The concluding reveals of each tale marked the first time detectives announced the solution and explained the damning logic as a story device. “The Murders in the Rue Morgue” is also the first “locked room” mystery. A mother and daughter are found dead in the sealed space deemed to be the crime scene. One was strangled and her body stuffed into the chimney, the other’s head has been severed nearly to full decapitation by a straight razor. There is nothing in the room but two bags of gold coins, torn hair, and the blade, still covered in blood.

“The Mystery of Marie Rogêt” is the first murder mystery based on the details of a real crime. Often subtitled “A Sequel to ‘The Murders in the Rue Morgue,’” the short story was based on the July 28, 1841 death of Mary Cecilia Rogers. The Connecticut-born woman was renowned as the “beautiful cigar girl.” Her reputation drew distinguished men to the New York tobacco store where she worked. Poems attesting to her beauty were published in the New York Herald, and her customers included Washington Irving, author of “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” which is set not far from the academy in The Pale Blue Eye. The 21-year-old woman’s body was found in the Hudson River, and the investigation caught nationwide interest. Theories included gang violence, a failed abortion attempt, and evidence included a boyfriend’s suicide note, but the death remains unexplained.

While not based on a true crime, the publication of “The Murders in the Rue Morgue” corresponded to the creation of London’s first professional police force, the first use of science in American police work, and the rising newspaper sensationalism of criminal trials. That generation of readers was among the first to be made to feel actively part of the reported happenings of the day.

The Armchair Detective Rests His Case

C. Auguste Dupin is also literature’s first amateur sleuth. In contrast to the film’s Augustus Landor, who is an ex-policeman with an impressive official success record, Poe’s intrepid investigator is not a detective, just a man with a reputation for possessing an acutely analytical mind who is asked to scrutinize crime scenes, and permitted to freely investigate. Dupin is a reclusive genius, but he has connections with people involved with the cases. He has no professional stake in their solution, it is a favor to him to pass the time.

In Poe’s stories, Dupin is a gentleman, mysteriously wealthy. He doesn’t need to work and lives a life of leisure. He is an amateur poet, preternaturally nocturnal, and works by candlelight. He likes to relax over puzzling pieces of nefarious transgressions while puffing on a meerschaum pipe. This is the same brand puffed on by the investigator who noted the trickery specifically inherent in “The Murders in the Rue Morgue” in the Sherlock Holmes story, “The Adventure of the Cardboard Box.”

In the last of the Dupin trilogy stories, “The Purloined Letter,” personal revenge is an added motivation for solving the crime. The investigator gambles his entire reputation over the case but keeps a close count of the cards. The fictional Dupin analyzes crimes based on external facts, but also has a taste for larceny.

The Real-Life Detective

Dupin is based on the real life criminal-turned-French Minister of Police François-Eugène Vidocq, who founded France’s national police detective organization Sûreté under Napoleon. Vidocqu owed his success to his experience in the criminal underground in Arras, Paris. Dupin shows off similarly illicit skills in Poe’s “The Purloined Letter,” duping the authorities and public alike in order to rest his case, and be celebrated for it. Vidocq was also a social butterfly, friendly with authors Victor Hugo, Alexandre Dumas, and Honoré de Balzac, and a staple of local news and gossip.

Vidocq left police work to run a paper mill, hiring former convicts for labor, but didn’t have a head for business and returned as chief of the detective department under King Louis-Philippe. After being dismissed in 1832 under accusations of organizing a robbery, Vidoqu formed his own private investigative force. The authorities of the time squashed its very existence, but it has come to be known as the prototype of modern private detective agencies.

In “The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” Dupin calls Vidocq “a good guesser.” In the first Sherlock Holmes story, “A Study in Scarlet” (1887), Holmes similarly dismisses the French detective’s fictional adaptation. “In my opinion, Dupin was a very inferior fellow,” Holmes tells Dr. Watson. “He had some analytical genius, no doubt; but he was by no means such a phenomenon as Poe appears to imagine.”

The Imaginative Sidekick

“The Murders in the Rue Morgue” was inspired by a contemporary news item. According to Romancing the Shadow: Poe and Race, edited by J. Gerald Kennedy and Liliane Weissberg, Poe was fascinated by a story about a crowd’s reaction to a healthy, five-foot, female orangutan shipped from Africa which was displayed at the Masonic Hall in Philadelphia in July 1839. The surprise ending in Poe’s tale is novel, breaking the logic up to that point. It was highly unorthodox and presented a seemingly brilliant unprofessional turn of events.

In the film The Pale Blue Eye, it is young Edgar who eagerly helps the eccentric but brilliant detective probing the academy murders. Poe walks up to the lead investigating officer and lays out his first clue, ultimately getting himself invited to participate in cracking the case, without any qualifications but a good opening line: “The man you are looking for is a poet.” Similarly, Poe lives out a fantasy, vicariously on paper, tripping over the perfect mystery due to sheer coincidental circumstance.

In the books, Dupin is aided by an ordinary helper who is a close personal friend, a trope which would later apply to Dr. Watson, who is at least given a name. The first-person narrator of Poe’s stories is an occasionally rash young man who never reveals his identity. It is fun to imagine the writer similarly going along on the case as the unnamed narrator in the short stories. The Pale Blue Eye offers a glimpse.The Pale Blue Eye is on Netflix now.