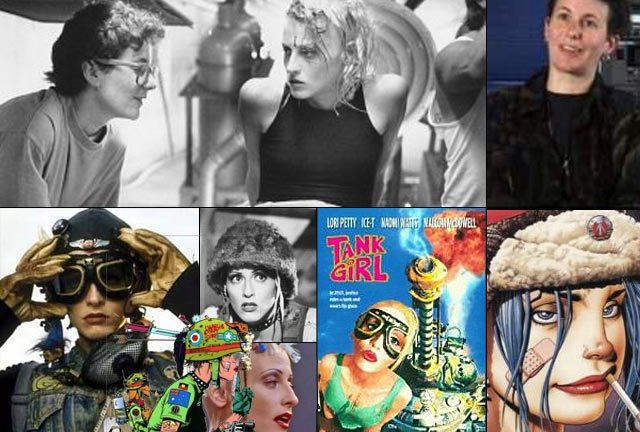

The Den Of Geek interview: Rachel Talalay

The disputes. The acrimony. The Spice Girls and Avril Lavigne! The director of Tank Girl talks with us at length about the project she would like to re-make...

Rachel Talalay began her movie career as production assistant and production manager on films such as Android (1982), and John Waters’ Polyester (1981). Her association with Waters would lead her to further work as producer on his films Hairspray (1988) and Cry Baby (1990), whilst her early work on Wes Craven’s Nightmare On Elm Street franchise culminated in her directing Freddy’s Dead: The Final Nightmare in 1991.

Entranced in the early 1990s by the post-apocalyptic heroine of English comic artist Jamie Hewlett’s Tank Girl series (co-created with Alan Martin), Talalay fought to bring the anarchic character to life on the big screen, finally securing a $25 million budget from MGM. The level of studio interference in post-production and the opprobrium of Tank Girl comic fans at the resulting movie makes the film/comic debate one that can still be ignited at a moment’s notice in movie forums everywhere. Personally I’m a huge fan of the film, and I guess Rachel thought it would be cheaper to talk to me than get a restraining order against my endless requests for a chat…

Do you meet many Tank Girl movie fans as rabid about the film as I am?

[laughs] Well, I don’t know to what degree, but – yes. It’s amazing to me. What makes me so proud of the movie is that in spite of everything that we went through and all the problems and how disappointed I am on some levels, and how much ahead of the curve I was when I made it, I still manage to have something that’s lasting. I get fan-mail now just like I did then. I wanted to make a movie that was the opposite of a bell-shaped curve – you either love it or you hate it. Judge Dredd came out at the same time, and it doesn’t have the same longevity because…at least I hit an audience that I was aiming to hit [laughs].

Presumably at some point the producers asked you who the target audience was, and researched it – how did that come out?

I didn’t see what wasn’t universal about it, in terms of the teen audience…skewing into the twenties and then skewing up to anybody who’s hip enough to like this type of movie. But it definitely was on the cutting edge at that point. Now you look at the movie and go ‘How can this be ‘R’-rated?’. But at that point – and it wasn’t that long ago – they made me cut so much out of it because they were so frightened of it. If we’d made it three years later, when the South Park movie came out and when everything skewed in the direction that I could tell it was moving, then it would have been ‘make the much hipper version that you want to make, and push the envelope further’. They were scared of their own shadows.

Since the mid-nineties was a strong time both for sci-fi movie production and strong female characters, were these factors that helped to get the film made?

I really don’t want to speculate. I don’t know how anything gets green-lit beyond the absolutely obvious. Now there’s discussion about wanting the more interesting cutting-edge again, and certainly in the UK. But who knew that Little Britain, for instance, would be considered family entertainment? [laughs] But there was an opening or a broadening of the audience once South Park took off. I think what I believe today is that there’s a general feeling in Hollywood that it’s very hard to hit the teen audience because they’re so busy playing videogames and watching their computer and everything, and it’s really hard to get them to watch TV and to watch movies; but I believe that they do come out when the entertainment is stuff that they want to see. So I think the fact that a lot of the entertainment – especially in the US – just isn’t targeted for them, and that they get it wrong when they target for them, and therefore that they’re not getting the audience because they’re not making the right material.

Is there too much focus-grouping and quantifying as opposed to letting someone with some talent just get on with the job?

[laughs] What’s been great about Judd Apatow and Seth Rogan is that they at least have their niche to say ‘We know how to do this, because you’re letting us be as outrageous as we need to be to appeal to that audience’. Superbad is really a good example of that. Tank Girl Superbad is what you wanted to do with Tank Girl. I think with TV audiences it’s particularly difficult as there’s this complete split down the middle of America, where the puritan world is saying…I mean, I’ve worked on TV shows where the girl can’t say ‘I want it’, or ‘Oh my God’. You’re not going to appeal to teenagers if you’re that dishonest, which is why there’s this whole debate about Skins playing in America; it would seem that Skins is the perfect show to repurpose for America, but no-one will go even close to anything that’s as interesting as that and as real as that. In a hyper-real sense [laughs].

Do you think a right-wing tendency would make it harder to put forward a really outrageous female character right now?

I don’t know if it’s because of the right-wing tendency or because it’s just become more and more conservative in terms of the finances, because things are tougher and tougher, as we all know, and the economy is really screwed up. So I don’t know if it’s so directly ‘We can’t have this female lead’, but ‘We need to be as commercial as possible’. And what is obviously bankable in terms of the big movies has always been male action, not female action. And I get that – it’s an economic world. But I think you could make a version of Tank Girl now because of Juno, and some of the earlier interesting teen movies like Mean Girls, or even Clueless. You can have a female lead as long as your budget is reasonable, and you’re not trying to turn it into a female action movie.

Would they have let you make a Tank Girl movie nearer your ideal vision if you could have delivered it for $10 million rather than $25 million?

We all made the decision. I had several offers to make the movie – we all made the decision to go with the studio. It was my ignorance and my confidence that I could handle the studio that was the mistake. The truth was that they were going to do whatever it was they thought was right, and I had absolutely zero say in it. There were numerous times in post-production when I called my lawyer and said ‘I want to leave the show’, and he said ‘No, you have to stay and fight, or nobody will fight for it’.

Was it ever going to become an ‘Alan Smithee’ project?

[laughs] Yes, absolutely.

That must have made you quite bitter at the time.

Yeah, I was probably bitter for ten years [laughs]. I’m not so bitter now, and I’ve been talking to the studio about re-optioning it. I went in and had a conversation with them, because in order to re-option it, I needed to make sure that they didn’t want to re-do it themselves. There’s nobody there who was there from the original days, obviously. You’re talking about a completely different group of people. So what I don’t want them to say really is ‘Yes, we do want it’, I want them to say ‘Yes, go ahead and option it and do it in the way you feel that you weren’t able to do it the first time’. Everything has moved on, everything is different now, and we can talk about it again.

I was in this conversation and one of the junior executives said to me’ But who is Tank Girl 2008?” [laughs]. And I just paused and went ‘She’s the kind of girl who would look at you and say “That’s the stupidest question I’ve ever heard”’. And then I laughed and then I disarmed that by saying ‘I know that sounds like an insult, but she is the person who would say the worst possible thing that could come out of her mouth in the worst possible situation to mess everything up, and that’s what I meant by that comment’. But what I meant was ‘I can’t believe you asked me a question as studio exec-ish as what we went through in 1995’. Nothing changes. I just went ‘I can’t do this with you again – why am I even in this room?’.

Would you really go through it all again?

Only if I could have an option where it was an option, rather than having to go through it with them. Needless to say, they said ‘No we’re not interested in doing it [themselves]’ and they thought it probably was a good idea for me to option it. But now we’re in a huge legal mess; there’s something that I don’t know about to do with the whole legal thing. It’s all held up again, so I don’t know what’s going on. It was a UA property, MGM merged with Sony…so there’s something in all that that’s put a legal hold-up that stops them saying ‘Yes – go with God’.

Are you able to look at version 1 with more affection and less rancour than you did back then?

Yes. But…yes and no [laughs]! I look at all the mistakes that I made, I look at what they did to them, I look at how important it was to me, and at the fact that people still absolutely love it and that there are people who will never get it – ever. But it’s exceedingly important to me because I made it for the right reasons. I made it because I wanted to make a movie about a strong woman who wasn’t afraid and would say whatever she wanted, no matter what, and who wasn’t afraid of anything. I made it because Tank Girl’s an icon of everything that I am and was and want to be.

Did you feel a character like that was missing from cinema in the period you were getting the project going?

I don’t think I was that specific in my thoughts. I got the comic-book, I fell in love with it, I was going to make it. There are funny stories about when I was first pitching it; the first place I went was to Jim Cameron’s company, and the executive there said to me ‘But we already have a movie with a female lead’. And I went [choking sound]. This is my first pitching ever, and I went ‘What? Well what is it?’ and he said Joan Of Arc [laughs]. And then I went to Spielberg’s company, and they said ‘We really appreciate you thinking that we’re hip enough to do this, but we’re not’. Jamie Hewlett just loved the idea that we were too hip for Spielberg.

That became kind of a slogan for the production, didn’t it?

Yes! It came because it’s actually what they said. And then I went to Dawn Steel, and she was passionate about it, but she was at Disney. She stood up on her desk when I took it in there and said ‘I am Tank Girl!’ [laughs]. So it was an amazing time because, again, people either got it or they didn’t.

But one of the things that happened was that when we sold it to UA, it was Alan Ladd Jr., and during the development time it was taken over by John Calley. And it was Calley who didn’t get it. Just didn’t get it. And that’s where things just went wrong. I don’t know what you do when you’re heavily into development and getting a film made, and you realise that your executive is the wrong person for it. You have to be awfully strong. I didn’t really know that it would go wrong until we got into post-production.

What happened to all the Sub Girl action in the film? Was that a casualty of studio intervention?

Yeah, and I don’t really know what made them make what cuts they made. There were scenes where we’d do a test-screening and a scene would be the most popular. One would be on the list of most popular scenes, and then they would recut it, take all the good stuff out of it and it would stop being on the list of most-popular scenes. So I would go and say ‘Here are your statistics – on this cut, twenty percent of people listed this as their favourite scene’…which is huge. Considering they have to list something, twenty percent is a large statistic. Compared to, you know, nobody listing it now. ‘So therefore, can we put the cut back the way it was? Because you’ve taken out what people liked about it.’. And they would go ‘No’.

So I remember calling my lawyer and telling him this, and he said ‘There’s nothing rational going on, Rachel’. And he was just brilliant, because he said ‘Nothing makes sense’. Normally you’ve got the director fighting the statistics and going ‘No no no, but I love that scene and it has to stay on’ and the studio going ‘but here we tested it!’. And here I was doing the opposite, saying ‘Look, we tested it and now you’ve emasculated the scene’ [laughs]. And people don’t care. And they’re going ‘Well tough, it’s just what we think’.

And it would be like someone going ‘I’m offended that there are dildos in her bedroom’, so that whole scene has to be cut out. Oh my God, dildos! [laughs] So that was how irrational it all was.

So who didn’t like Sub Girl? I don’t know. It could have been somebody’s mother, as far as I know, because they kept me from all the internal discussions. They just said ‘This is what you’re doing’. And then I fought, and I have to say that I got probably twenty percent back by just fighting and fighting and fighting. I got about twenty-thirty percent back of what they pulled out. So by sheer will I wasn’t completely unsuccessful. I think that the movie doesn’t flow because they didn’t care – not that it flowed brilliantly to start with, but I always said that the plot was less important than the sense of the whole movie. But it really feels choppy because they didn’t care where they pulled anything.

For me, for instance, the musical number – they chopped it to shreds. Finally the music supervisor went in and said ‘You cannot put this out like this’. They took half the stanzas out, so that it didn’t even cut, and she asked them to at least give her the length that they wanted and to let her cut it so that it wasn’t a travesty. We went in and re-did it so that we got it the length that they wanted it, so it wasn’t so musically hideous [as the studio’s cut]. It’s still missing one of my favourite stanzas…

That’s the one where Naomi Watts joins in?

Yup.

I noticed it in the excised scenes at your website.

The good thing is that nobody ever complained to me when I put that up. The first time I put that up at my website I was like ‘Holy shit’ – you know. And then I thought, you know what? If they come and complain, I’ll just take ‘em down. But they haven’t, and now whoever took them off my site has put them up on YouTube, and they’re all…[laughs]. It just goes to show how shitty VHS was, when you look at the quality of those transfers onto VHS. I wish I had some of the other cuts that we did, but I don’t.

Do the legal issues mean there won’t be a special edition of Tank Girl anytime soon?

What happened was that when they put the VHS out, I was very upset – we shot in widescreen, in Cinemascope, and when they put the VHS out they didn’t even bother to letterbox it. VHS is 4:3, which means forty percent of the frame is missing. They didn’t give a fuck. So when they finally decided to put it out on DVD, I had some kid who became really obsessed with it, and he got involved and kept writing to MGM saying ‘Can you please put out a widescreen edition’, because the only place it came out in widescreen properly was on laserdisc. And he said ‘Please please please, here’s a list of all the special features we’d like’, and he sent a petition and everything. He emailed me about it – that’s what I love about the internet; you would never know stuff like this was going on without the internet. So he got in touch with me and I said ‘Please, yes’. And I gave him some suggestions for special features; I have all this material, I have this and this…

It’s a shame now, because Stan Winston died. Stan was the biggest fan of the movie. He was the best! He just thought that the rippers were some of the best work that he’d ever done, that they had to stand right next to the Terminator in his museum…which was fabulous.

So they said ‘Oh yes, we’re putting out a widescreen edition’, and they put out the DVD in 1:8:9, not in 2:3:5 and they said ‘Oh, we thought that was widescreen’. So really the only place you can get the proper widescreen version is still on laserdisc. I would love to do [a special edition]. And they put zero zero special features on the DVD. And the answer is they really don’t like the movie, they really don’t care about the movie; they really can’t see it. If this was New Line, they would have put out five different editions by now.

I’ve done so many interviews for Nightmare On Elm Street, it’s insane! I’ve told the same story thirty times [laughs]. But they just don’t care. Period. So the answer’s no – I can’t imagine they’re ever going to do it. What’s missing is that there are these rabid fans – I have a fan in Pennsylvania who’s bought every single prop he can get his hands on, who basically has his own Tank Girl museum of all the props.

And then there’s Catherine Hardwicke [then Tank Girl’s production designer], who would love to do it, and whose house even now still has all this Tank Girl material, because it meant a huge amount to her to do that movie. Even with her own brilliant career that she’s having, she would still come and do special features because it was something that she really cared about and really got. So I think it would be brilliant doing something like that, but I don’t see MGM as being the place where it’s ever going to happen.

Since the management has changed, why are they still hostile?

Recently I was told ‘There’s somebody there from the old days that doesn’t like you’. I was told that and I was like ‘Grrrr…ok! Whatever!’. How am I supposed to respond to that? Do I get over it after thirteen years?

One chess-piece to fall and we’ll have the special edition, then?

I have no idea. I don’t believe that they believe that they would make enough money to spend the effort to do it properly. But wouldn’t it be great? I’d love to do a director’s cut. Stan, when he built the rippers, did a full naked version of Booga, and he shot it. I mean full anatomical [laughs]. We shot some outtakes of this completely naked creation, and I would love to go back and get that footage, because that would be enough to sell it.

You probably knew that you weren’t going to get away with all the cross-species sex in the Tank Girl script…?

Well that [naked ripper], I knew we weren’t getting away with, but since Stan built it, I was going to shoot it; there was no way I wasn’t putting it on film, even though I didn’t mess up a scene. I just did an extra little take on it knowing that we wanted the footage on film. If anything it was just a gift to Stan because he’d done the work [laughs]. The guys were so enthusiastic – they loved building that. And they were making Congo at the same time, and they were so bored, and it was so much more fun for them than making gorillas.

There’s a polar divide of opinion on the film, with every rabid fan having a counterpart who hates it in favour of the comic…

Yep.

You loved the comic yourself, and that’s why you made the movie, so does that response confuse you?

No, I totally see their point of view. I don’t see that I represented the comic. I think people who hate me because of it need to understand how difficult it is [laughs] in this world, but I completely get that they think that I don’t represent the comic properly, and they’re allowed to be angry. I think Jamie gets that the comic will always be better than the movie. But I occasionally read things like ‘Why didn’t Rachel just stand up and..’ blah blah blah, and I think ‘Boy, you have no idea. I’m happy that you can think that and hate me, but you have no idea what it was like being in the middle of what I was in the middle of’. To try and fight…

But I don’t resent at all the comic-book fans who feel I didn’t succeed, because I didn’t succeed.

Was all the interference in post-production or did it ever impact on principal photography?

There was a bit of interference while we were shooting…there was pressure on the script and there was some interference during the shoot. But there was full interference during post-production, during the editing.

I’m the first to admit that I’ve made numerous mistakes, but I guess what I would stand up to with those fans is that I didn’t miss the point of the comic. I get the comic; it was just part of that time and that world and I would make a completely different movie now. But it doesn’t matter what you do, you can never please the hardcore fans who believe they have ownership of something. That’s a specific personality. I didn’t set out to piss them off. I set out to break the boundaries as best I possibly could within the parameters of what Hollywood would permit, and I failed. But I did set out to do that. I felt that I could be the female director who could break the boundaries…

If you look at the statistics now, there’s fifty percent the number of female directors as there were when I made Tank Girl. Now you’re talking about eight percent versus sixteen percent. What is wrong with this picture? It hasn’t gotten any better, and I was really hoping that I was going to be the breakthrough movie.

What do you think it would take to improve that situation?

I don’t know – it’s so engrained. And it’s so depressing that it’s so much worse. I think that the economy needs to loosen up, and I think probably there is going to be such an upheaval in the way that films are made because of the changes in the digital world and everything, that that might make a difference. But I don’t know – I don’t pretend to understand the market-place.

I know that there is a large audience out there for the kind of [Tank Girl] movie that we could make now, that gets this character in and being the outsider, and the anti-authoritarian fighter. And even moreso now. Just having tattoos was a big deal when we were making it! Now everybody and their uncle has tattoos. That’s how much the world has changed in these ten years.

Was your work with John Waters a big influence on Tank Girl? It seems to creep in, particularly in that musical number…

Yeah – I never thought about it, but he’s so much part of my sensibility and my life…but I never thought ‘Let me go out with John’s approach’. Because nobody is like John. But I think he opened my mind to the anarchy, for sure.

The casting of the film was a huge publicity event in New York and London…

Yes, we had these great open casting calls, which were an absolute blast, and that’s where the Spice Girls first met; in London there was a three-hour wait to come in and it came to the point where you’d just come in and meet people; you couldn’t do anything, because there were so many people and there was no time. We’d just get them to come in and do something or say a few words about themselves or do whatever they’d prepared..

But apparently two or three of the Spice Girls were in line next to each other and just said ‘Oh, fuck this – let’s go make a band!’ [laughs]. I just like the fact that I had something personally to do with the Spice Girls.

Did you get very far with Emily Lloyd before shaving off her hair became an issue?

Yeah, we were well, well into prep with her. And then she wouldn’t shave her head, wouldn’t shave her head, and it just became more and more apparent that she couldn’t get there. People say to me ‘Oh, it was apparent then that there was so much wrong with the production if that happened’, and to me…that’s when we knew things were not right. To me it was just so simple – if you can’t shave your head, you can’t be Tank Girl. If you can’t get to that point…we tried bald-caps, we tried different wig things; they just all looked crappy and it was just going to be a huge amount of work. It was all part and parcel of not being able to get there. Rehearsals went well; we were well down the road, but I felt like we had hit a wall. And it was disturbing her so much. So we just agreed that it was better to part company than to get to the point where she just couldn’t function.

So was ‘Will you shave your head?’ the first question you asked Lori Petty?

Oh, we’d asked Emily before we started. But that’s the same thing as ‘Can you drive a car?’. Like doing Wind In The Willows – it was no surprise when I found out that Matt Lucas couldn’t drive [laughs]. It’s Toad Hall and Matt Lucas couldn’t drive! Oh okay – par for the course. But with Matt, it didn’t matter – I had a good back-up plan on that off chance. I’d much rather have Matt Lucas than somebody who could drive [laughs]. Absolutely no question. So I’m not casting aspersions on Matt in any way, and I don’t think they even ever asked him if he could drive. He was so good for the part, we would have done anything to have him.

But with Emily it was definitely ‘You’ve got to be able to go out there and not be frightened of shaving your head’. One thing Lori Petty said was that she’d done everything; her own stunts, song and dance – even though she didn’t do that. She wasn’t afraid of going out there and doing whatever she needed to do. Which is true – she was completely gutsy and un-frightened of whatever we asked her to do.

Many have had fun casting a new Tank Girl movie, with Fairuza Balk and Gwen Stefani often mentioned. Who would you cast in a new version?

Well, I’d go younger now. I’d be looking for somebody new and younger, 18-20…so there’s no name that jumps to mind at this point. It’s odd, because I’d be looking for young, interesting rock and rollers. Avril Lavigne is probably the only person I can think of that has that kind of attitude. There’s much less of that attitude out there at the moment in the rock world. You have to look harder for it. There’s much more sort of Disney-teen stuff out there.

Rachel Talalay, thank you very much!

You can find out more about Rachel’s work and see the excised Tank Girl clips at www.racheltalalay.com