The Brain From Planet Arous: Inside a Cerebral Cult Classic

The Brain from Planet Arous star Joyce Meadows talks about her experiences in a beloved b-movie sci-fi classic.

Early science fiction movies presented mind-bending possibilities for audiences who were new to the idea of alien invasion. Made five years after the July 1952 Washington, D.C., “Big Flap” UFO sightings, The Brain from Planet Arous (1957) presented a more thoughtful takeover: alien possession. Gor, an evil intergalactic brain, invades the human body of an atomic scientist, with plans to conquer the world. The cult classic has been restored with a 4K transfer by the best minds at the Film Detective for a special edition Blu-ray and DVD.

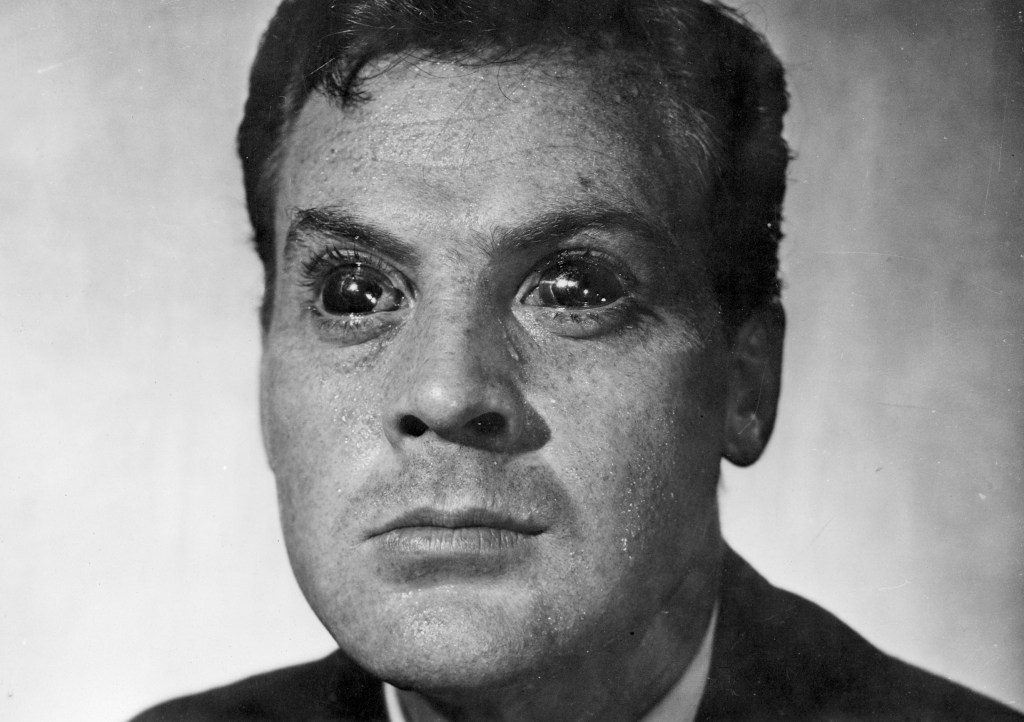

The low-budget, independently produced feature was directed by Nathan Juran, the genre master who gave us The Deadly Mantis (1957), Attack of the 50-Foot Woman (1958), and The 7th Voyage of Sinbad (1958), produced and photographed by Jacques Marquette, and released by Howco International. The Brain from Planet Arous stars John Agar, a consummate B-movie favorite (The Mole People, Revenge of the Creature) as scientist Steve March. Joyce Meadows (The Christine Jorgensen Story, The Girl in Lovers Lane) is his analytically grounded fiancée Sally Fallon.

Meadows made her film debut in the western Flesh and the Spur (1957) which also starred Agar. She entered the theater world when she was eight, and had been a stage actress and singer since high school. Her film characters often met tragic ends, but Meadows’ television work consistently brought happy challenges in progressive roles, sidestepping the dizzy stereotypes of the time.

Meadows, who never stopped making music or performing live in theater productions, recently revisited her role as Sally Fallon in the 13-minute introduction and comedic featurette, “Not the Same Old Brain,” included in the DVD. She spoke with Den of Geek about the terrors and beauties of giant brains.The below interview has been edited for length.

Den of Geek: The Brain from Planet Arous was your first full movie, what was the transition from live theater to sets like?

Joyce Meadows: Well, as far as developing characters, bringing the moments alive, my theater background helped all of that. The challenge was the technical things. The Brain from Planet Arous had a lot of different camera moves, and I had to learn to find my marks without looking at them. Actually, the director, Nathan, would just let me walk through that a couple of times, hitting my marks, because that was important to be on camera.

The other difference was: in plays you start with scene one, and movies or TV, they could start with the middle of the script, or toward the end of the script, and then go back to the first. It never was in sequence. You had to remember things and connect as an actor and not lose whatever work you did, no matter what you were going to shoot that day. Those were the two biggest things.

How did you get the reality of Sally Fallon’s rougher scenes with Steve Marsh? How did you get John Hagar to let go so violently?

Well, that was the first time John had to play a bad guy, and a good guy. He jumped in and, I think, surprised himself. Those contacts he had to put on, were usually done very quickly, because they were hard contacts. His eyes would just start watering, and go to pot after a minute or so. The hardest thing for John was putting those on and off, which he had to do a few times. But, I tell you, he just did, I thought, a very, very good job of that. And that was his development of character. With the help of our director, of course. And so, I responded.

If the script called for it, would you have put on those contacts? Because I would have quit the profession rather than do that.

Well, if you’ve accepted the role, you commit to what’s being done, and what the script has. That’s how the monster showed himself. John did, and I probably would have done the same thing if the monster had taken over my body. Because actors are a strange lot. The show must go on, you know.

You saw the big brain for the first time at the shoot. When you’re acting against a prop, do you assign it human properties in your mind, or is it not much different from working with a wooden actor?

I never saw the brain being built or created or anything. I never saw it until I was in the caves. The reaction to it and the eeriness of the darkness, and the weird lighting and stuff, created a very easy illusion for me to scream and respond to it. I did emotional memory. And for the rest of the movie, whenever that brain was around that’s what I saw, although there was nothing there but empty space. It was there as far as my emotional memory was concerned.

John and I never discussed it, how each one of us did it. There usually wasn’t enough time. I never saw the brain again until it came at me at the very end of the movie. Then John picked up an ax and was trying to do the brain in. Those were the only two times I actually saw the brain. Now, it’d be different in the movie, of course, but it was just the emotional memory that I had. I responded every time the brain was supposed to be there.

Sally was your only science fiction role. But you had a recurring role as Lynn Allen on the TV series, The Man and The Challenge. That seems like a very progressive role for the time. Did you find science fiction sets and the artists who went into these genres different from the ones who did westerns or detective stories?

They were very, very different. Because they were sci-fi, and you had to believe things that were not believable. You had to be involved in situations that human beings have never been involved in yet. Who’s ever met a brain from another planet, that subsystem, and different experiments? It was a whole different kind of commitment. I loved them. I wish I had been around for Star Trek. I was away from Hollywood, pretty much, at that time and out on the road in the theater. I wouldn’t miss Star Trek. Even though I was away, every Thursday night was Star Trek. And I was right there in front of the TV.

You made three appearances on Alfred Hitchcock Presents. Was working on a show like that different from the usual sets?

Well, the way the show presented itself, Alfred Hitchcock came on talking at the beginning of the show, on another stage, all by himself. He never directed any of them. I never met him, he was never available or around any of the production of the actual television shows. They were all different directors. I thought the scripts for television were very well written and easy to do.

At that time, a lot of the Actors Studio people were performing. Behind the scenes, a lot of directors just didn’t know how to gel with that. I had a Stella Adler background, and as an actor, that didn’t bother me, because they were quite different in front of the camera. It was a whole new genre coming on as far as acting, and the scripts were very well written. I could mold into them very easily with the characters. We had nice directors that if you did little, you were given direction. But if you added something, as far as a gesture or a movement or something, they accepted it. I know I enjoyed the three films. I thought the show was quite good. One of his relatives, a niece or somebody who is female, was the big producer on the television shows. And that was the basis of Alfred Hitchcock.

You are in one of the most pivotal scenes in The Christine Jorgensen Story. Did it feel daring to make in 1970?

She was on the set all the time. As I understand it, she was the first person who had a sex change. She went to Denmark or Sweden. She was very much a woman when she was on the set every day, I thought it was very fascinating. But I think it was the beginning of accepting, or at least becoming interested in, that type of thing.

Of course, my part was before she did anything like that. When she was younger, she was a he and had a girlfriend. I was that girlfriend in the movie. But later on in her life, I don’t know how young she was, but I would assume she was in her late 40s when she was on the set, she was there every day. I guess they needed her to verify things. It was her story, actually. So, I guess, obviously, that’s why she was there too.

You were on Wanted: Dead or Alive. What was Steve McQueen like to work with and what was he like when the cameras were off?

I got to know him very well, because in between scenes and stuff we became chit chatty on the set, talking about our careers. Steve was very ambitious. At the time, if you did a television series, no studio wanted you for a movie because they said if audiences can see you for free, they’re not going to pay to see you. He decided he was going to change that. He was going to go into movies, which he did and succeeded, but he talked about how he was going to do it. He was a very, very dedicated actor. He had the Actors Studio background, which a lot of directors had a hard time with off and on, but they learned how to contend with it, even in the movies. They were attacking him nicely about it, like “let’s not have so many pauses in the scenes,” or something like that.

He was fun to work with because we both had the Stanislavski background. And my part was really interesting because I had to ask him to marry me, in the segment I did with him, because I needed a husband to save my son, whom the child’s grandmother wanted to take away from me. I needed a husband right then and there. I thought my idea was to bring in somebody like him, who would understand. Well, he didn’t, quite, as the scene went on. He was a little shocked. So, there was some nice acting between us.

It was fun because we both were technically from the same background, although he was Actor’s Studio and I was Stella Adler. He was very, very strong and very ambitious on what he was going to do. And I was impressed with that. And I thought, I wish I could have used some of that courage. But he was quite courageous about getting into the movies after that television show. And of course, he did so well. He did The Blob somewhere in there.

Because this is Den of Geek, I have to ask what you remember about working on Lois and Clark: The New Adventures of Superman.

Not too much, only because I was a judge, and I came in and did that scene. I think I only had one scene that night. And that was it. I don’t remember too much. I grew up with Superman and I thought Christopher Reeve was the best image I had as a child of what Superman looked like.

I am personally a huge fan of Poverty Row films and the smaller studios. What were they like to work for? Did you feel like you were part of the history of indie film as you were doing it?

Oh, yeah. I embraced it. Emotionally. I thought it was wonderful. They did not have independent films. If you wanted an actor, you still had to deal with a Screen Actors Guild and eventually, business wise, they made a deal according to someone’s budget. And as years have gone on, it’s become, with the computers and cell phones and all the communication, a beautiful world for young people to learn the trade, of directing and producing. I think it’s evolved into something quite wonderful.

You worked with William Castle on I Saw What You Did. How difficult was the shower scene to shoot, and does choreography add to the performance?

That bathroom scene probably was the same way as [the shower scene in Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho]. A lot of reactions, close ups. It was your imagination. Because really, there was nothing being stabbed. It was so technically done. Of course, in order to make it real, I had to commit to the idea that I was being stabbed. So, I threw myself into that feeling of being murdered. I don’t know what technical things they did, because I was busy, being murdered, so to speak. I think the Hitchcock film was somewhat the same way. A lot of technical things. Of course, when it’s put together it looks very real. It was fun playing a heavy, I enjoyed that. A lot of times my parts were a good person, so I enjoyed being a bad girl there.

What issues did you have on that film with Joan Crawford?

Joan Crawford was the type of movie star that would never come on the set if a young actress was on the set. So, I had to complete everything I was supposed to do on the days that I did it, and then she came on set afterwards. But I was gone. So, I never met her. I know she was one of those old stars that didn’t want to be around young actresses. For whatever reason, I don’t know. You can speculate. All I know is that they did all of my stuff. When I was through, and gone from the set is when she came on, and began hers. But I never got to meet her because she wouldn’t come on the set.

Can you tell me about your death scene in The Girl in Lovers Lane?

Jack Elam, who murdered me, was the sweetest, gentlest soul, and when he had me down on the ground, looking at me with one eye going one direction and the other… I mean, that’s why he played heavies: This face, it would scare you. I knew him, and I knew what a lovely person he was, and I couldn’t help it. I started to laugh, and went completely out of character. Of course, the director would yell “cut let’s get something serious happening.” Jack was just a lovely person, and would scare you like crazy in his westerns and things. And he’s the one that played that part where he literally killed me. I thought the movie was very good.

You walked away from film and TV and went into theater just as the independent film movement had its renaissance.

I did. And nobody convinced me. If I’m unhappy about that I’ve only myself to blame. Sometimes you can kick yourself around the block on things. Certain things in your life. Well, I shouldn’t have done that. I should have stayed, but I didn’t. If an actor has certain regrets, that’s one of my regrets as an actor.

Was the theater world as sexist or sexually oppressive as the film world?

No, no, you didn’t have that. And of course, there was no such thing as sexual harassment, it just was something you had to deal with. But in the theater, no, I never ran into that. In all the theater that I did, I never did have that problem, never did. But it was pretty constant in Hollywood. I don’t go into it and I don’t write about it. So many actresses already have. There’s nothing more to say about it, except it was something we all had to deal with.

What was it like returning to the Sally Fallon character for Not the Same Old Brain?

I had a couple of weeks to look at that script, and I had notes in my old scripts. The only difference is there I was Sally then, but I had to be Sally now. She’s still at the camp, she still got the pith helmet, looking for brains out there that may be trying to take over the world.

The Brain From Planet Arous Special-Edition Blu-ray + DVD will be available starting June 21.