Steven S DeKnight interview: Pacific Rim 2, monsters, suspense

We chat to the director of Pacific Rim: Uprising about John Boyega, the meaning of monsters and why blockbusters can be so long...

If you’re into your American genre TV, then you’ll probably know Steven S DeKnight’s name from such hit shows as Spartacus, Buffy The Vampire Slayer, Smallville and Daredevil. Pacific Rim Uprising, meanwhile, is a very different proposition: not only is it DeKnight’s first feature as a director, but it’s also a sequel to Guillermo del Toro’s giant-monsters-versus-giant-robots movie.

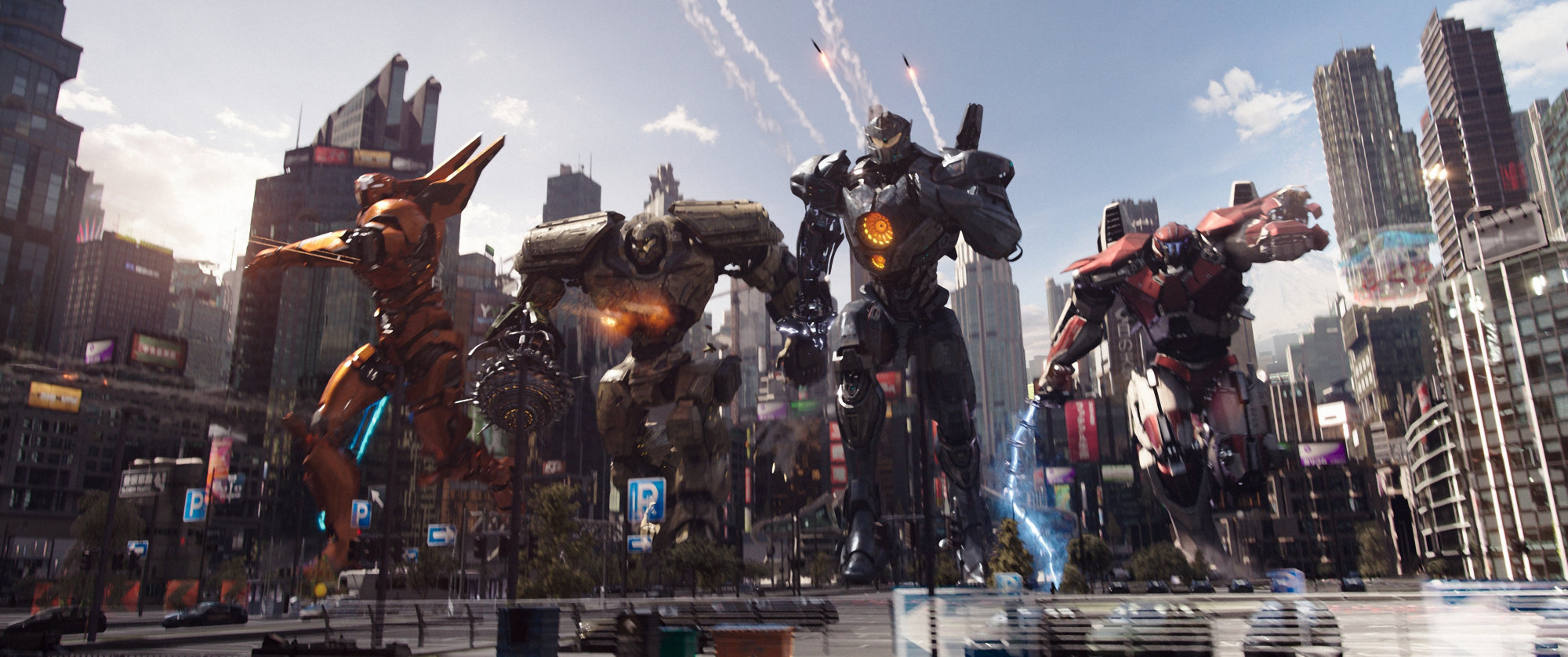

Taking place a few years after the 2013 movie, Uprising introduces John Boyega as Jake, the son of Stacker Pentecost, one of the heroes who fought the giant alien creatures (or Kaiju) in the previous battle for Earth. When another monstrous threat emerges, Jake Pentecost leads a new generation of recruits into action, and as before, they heroes are piloting giant robots that require two people to control them.

Like its predecessor, Pacific Rim Uprising is a fun, fast-paced B-movie writ large. DeKnight clearly shares del Toro’s affection for robots and monsters, too; when we met him for a chat in a London hotel, he talks excitedly about everything from special effects to writing to the secret of suspense.

Here’s what he had to say…

I really enjoyed the film. And John Boyega’s a real coup in this, because he’s one of those actors where you feel you already know him right away.

He is, he is. I’m so lucky to have gotten him for this movie. I loved him in Attack The Block and, of course, Finn from Star Wars. I think people will see him in a different light in this movie. I was telling John when we were shooting the movie, “You’re like a young Harrison Ford. You’re like Indiana Jones and Han Solo – you’ve got that kind of charm, but you’re a little bit outside the hero realm. You’re a little rogueish.”

If you’ve ever spoken to him, it’s not an act, him being so warm and funny and charming. That’s him, 24/7. So he was a delight to work with.

How did the story develop, because it’s quite a difficult act to follow, the first film.

Yeah, Guillermo has giant shoes, and now they’re gold plated! So the first thing I did, when I was approached, was rewatch the first movie. I had it on Blu-ray of course, because I loved the first movie. I knew I wanted to honour what Guillermo did, but take the franchise in a broader direction. I sat down and started thinking – I drew up on Ultraman and giant robots, all the man-in-suit movies. I loved the genre, so I thought, what would I like to see? What would excite me? I wrote up a five to eight page broad-strokes story, sent it to Legendary, they really liked it, pitched it to Guillermo, he liked it. Had some great suggestions.

From there, I took a page from my TV experience, and put together a writer’s room for two weeks, and put together some TV writers and feature writers. We started to fill in the blanks, craft the world, name the Jaegers, name the Kaiju. And out of that group of people I chose Emily Carmichael and Kira Snyder to help me write the first draft of the script; then, later in the process, when John Boyega was cast, I brought in TS Nowlin, the writer of the Maze Runner movies, to help me retool it for John.

So that was basically the process. I came in with an idea for a beginning, middle and end, the villain, the cadets, all that stuff. And then we just really threw our back into beating out every single scene.

You’ve done a lot of action in your TV shows, so did that prepare you for the action in this, or did the CG heavy quality of it mean it was a new thing?

No, the TV work absolutely prepared me. I never could have done this movie without the TV work. Thankfully in TV, I was used to working with action and stunts and CGI. Not on this scale – I always say this movie is what I did on TV, just a hundred times bigger. But the great thing about working in movies is that you have just a fantastic group of creative people helping you carry that weight.

I saw another interview a while back where you said that working with CGI action sequences isn’t much different from working with actors. I just wondered what you meant by that? Has it reached the point where it’s become easier for directors to direct that kind of action?

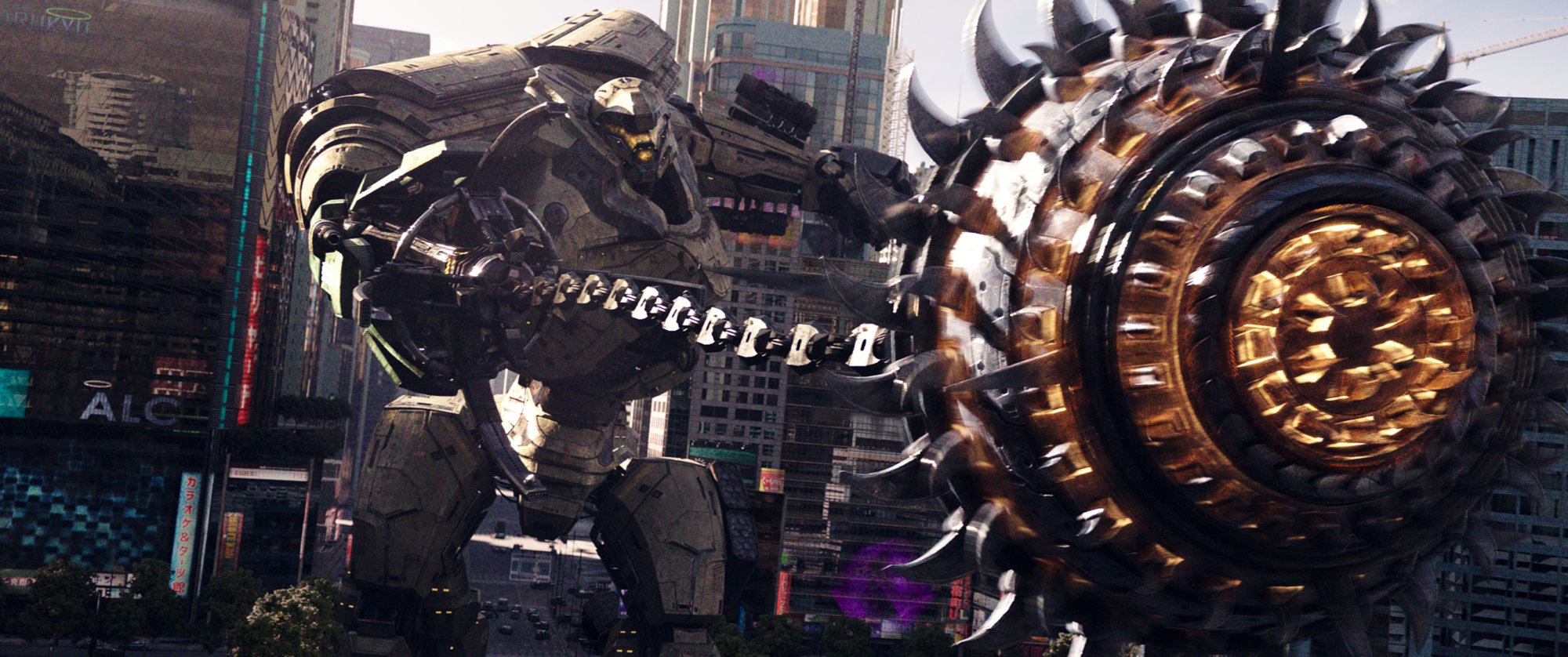

Yeah, I approach the CGI stuff the same way I approach actors. It’s about story, it’s about character, it’s about, what do the monsters want? What are their goals? What are their personalities? I think if you start like that, it really helps. Then with technology today, especially in a movie, one of the biggest differences between doing the CGI stuff on television and in the movies, is pre-viz. Television never really had time for pre-viz. We storyboarded everything for the movie, and then that went into pre-viz, the rudimentary, stripped-down animatics.

Then I always had an iPad with me, and I always had the pre-viz, so I could show the actors and we all knew what was going on. Really, designing those action scenes – again, it was just the little kid in me saying, what would I want to see? I want to see mega Kaiju! One of the biggest action scenes in the movie, of course, is the finale in Tokyo. That was a special case, because the writers and I approached it like its own mini-movie, where I knew I wanted a beginning middle and an end to tell the story. What I didn’t want was Jaegers punching Kaiju for 25 minutes; it had to have ups and downs and dips and turns and surprises.

I think that’s one thing where these big CGI movies often fall into a trap. We’ve got to make sure those action sequences have the same kind of ebb and flow and storytelling as two people in a room talking.

Absolutely. It’s interesting how you talk about the kid in you. Because one of the things I thought when I watched the film is that kids love giant monster movies. I wonder if you think that’s because kids grow up in an adult world where everything’s too big for them…

Yeah, yeah! That’s an excellent idea. I’d never thought about that, but it’s quite possible. Everything is big and scary when you’re a kid. When I was a kid, I loved dinosaurs, and the giant monsters were like dinosaurs times a thousand. Yeah.

I like the idea of the Drift, which you brought over from the last film: the idea that you’re putting trauma out of your mind, and uniting to fight a monster. That’s a positive sentiment.

That’s something I definitely wanted to carry over, and something that makes Pacific Rim so different from other giant robot franchises. It’s the soul in the machine: the technology is nothing without two people inside it who have to put their differences aside and work together to make it operate. To save the world. I thought that was such a brilliant concept from Guillermo and Travis [Beacham, screenwriter] in the first movie.

One of the things I like about this film is that you have people from different nationalities coming together.

Again, I wanted to take what Guillermo and Travis did and push it even further. In the first movie you had Chinese pilots piloting a Chinese Jaeger, and Australian pilots piloting an Australian Jaeger. I wanted to advance that, so that the Pan Pacific Defence Corp, their Jaegers don’t have nationalities – they’re just the world’s Jaegers. I also wanted to mix up who’s in the Jaegers: you have a Brit with an American operating Gypsy. You have a Japanese kid and a Latin American girl operating Sabre. So that it really is truly the world coming together.

It’s interesting how Hollywood’s become more outward looking. If you go back to the first Godzilla, where they brought it over and put Raymond Burr in there.

Ha! Dear Raymond. Yeah. I think I was in my early 20s before I found out that Raymond Burr didn’t belong in that movie. And when I finally saw the original, it was so powerful and so beautiful – such a statement. I love Raymond Burr, don’t get me wrong, but it was like, “Ugh! The Americans ruined Godzilla by jamming in an American sub-plot.”

It struck me how much has changed in the past 50, 60 years. So technically, which part of this movie was the most difficult to conceive?

Oh boy, every single part of it. The hardest thing in a movie like this is, there’s a tendency to let the action and the CGI carry you away. Thankfully, coming from television, to me it’s character and story that’s the most important thing. And really, one of the hardest things about this movie was trying to craft characters that are entertaining and fun, that have some emotional core to them. That was the most difficult thing – especially in a two hour or under movie. It’s very difficult to give every character in an ensemble like this their moment.

You gotta concentrate more on the main characters. So it’s trying to make the characters human and relatable. Because if your audience doesn’t relate to your main characters, no amount of CGI is going to save you – the CGI just becomes boring if you don’t care about the characters. Again, that’s one of the reasons why I’m so grateful to John Boyega for signing on the movie, because the moment you see him in on the screen, I think the audience gets attached to him, and wants to follow him through the story. It’s the same with Scott Eastwood and Cailee Spaeny [who plays Amara]. It’s her first movie, a very important role. But if you can get the audience to be engaged with the characters, they’ll go along with the CGI ride.

I like the part with John Boyega eating the ice cream in his dressing gown. I don’t know how that came about, but I’m glad it exists.

Yeah, and it’s one of those things where we started talking about various permutations of that scene. At first, I was like, “Ah, do we really need it? It’s the first act. We’re spending a whole scene in a kitchen.” But [producer] Mary Parent really pushed for the idea, and I’m so glad she did because once we got into it, because of course, it makes the audience love Jake even more. He’s in this ridiculous robe having a late-night beer and ice cream sundae, and it also really helped Scott Eastwood’s character.

One of the recurring themes in the movie is emotional connections, and how people have parted ways but are trying to make their way back to each other. You see it with John and Scott Eastwood’s characters; you see it with John and Rinko Kikuchi; you see it with Amara, who’s been separated from any sense of family. You see it with Charlie Day and Burn Gorman. So this idea who used to be close trying to find a way back to each other is so important. That scene, I think, really crystalised that idea. They don’t hate each other; John left the programme, and if you look a little deeper in the scene, Scott’s still hurting because his best friend left him.

I saw somewhere else that you wanted to keep the film around the two-hour mark, or under. I thought that was an interesting point, because a lot of blockbusters now do tend to bloat outwards to the three-hour mark. I wondered why you think that happens?

I have absolutely no problem with a two and a half hour, two-hour 45 minute movie, depending on the subject matter. For me, when you get to Jaegers and Kaiju, this kind of B-movie – and I say that lovingly – I think you can get carried away with feeling a little too self-important. You get so many great ideas. I could’ve made a three hour version of this movie; there are many great ideas that we snipped out, because we realised, “Listen, if we push this to two-and-a-half hours, I think we’re gonna lose the audience”. I think this movie works better as a fast, fun ride – emotionally, I think it works better. I would rather have somebody come out of this movie saying, “Wow, that was really enjoyable. Wish it was a little bit longer” than somebody coming out and saying, “That had some good parts in it, but man, you could’ve cut 20 minutes out.”

There is a tendency to make movies a little bit too long. But I do think it’s got to be a case to case basis. If your story and your subject matter requires you to go that long, then absolutely. If it doesn’t, then you have to murder some of your beloved children and tighten that up.

So what’s the process of that tightening like? Is it a case of paring down your B and C plots, or…?

Yeah, it’s doing that. There were a lot of great additional action moments that we came up with. You start to look at them, and you say, “Yeah, that’s cool, but is it necessary?” There’s that action that we’re doing here, does it take away from something over here? Are we just gilding the lily because we’re excited about the idea? [Spoiler redacted] Sometimes you can just go off on tangents that are great and wonderful, but the aggregate of too much is that the audience just gets exhausted.

I saw that before this you were prepping a small thriller…

A very small thriller, yes!

Is that something you still plan to make?

Yeah, I’m hoping to make it later this year or early next year – time permitting in the schedule. I love classic suspense movies, and I’ve gotten a bit disheartened with horror movies lately, because they seem to have a great first act, great second act, and then a lot of them just seem to fly apart. Not all of them – there are one or two great ones out there, Get Out being a huge, huge exception. So I really wanted to craft this throwback to the old Hitchcock days – a movie based not on jump scares, but suspense, keeping the audience guessing about what was really happening.

I wrote this movie called The Dead And The Dying, which is literally three people in a house. A very twisty, turny Hitchcockian story. That was supposed to be my directorial debut – I had set it up with Mary Parent at one of the studios, and it was just taking a long time to go through the studio process. That’s when Mary called me out of the blue and said, “What do you think about Pacific Rim 2 instead?” Anybody would be a fool to turn that down. But yeah, I hope to shoot that sometime this year or sometime next year.

So what’s the key to suspense in storytelling?

It’s the classic Hitchcock thing. If two guys are sitting talking at a table on a train, and all of a sudden the train blows up, there’s a moment of shock. But if you show the bomb under the table, and they’re talking, and the bomb’s ticking down to zero, then you have the audience is going, “Stop talking! There’s a bomb under the table!” That’s just the classic thing – to build tension.

Then of course it’s the way you shoot it, the way you frame it, what’s in focus, what’s not in focus. What you do see, what you don’t see. Keeping the audience guessing. Psycho’s a classic example. It’s a very hard thing to do correctly, I think, and the movie I want to shoot is quite daunting because it could easily go wrong. Any movie’s difficult, but straight horror is a bit easier, because you’re looking for the jump-scare, the gross-out moment. Suspense is almost like a forgotten genre in movies. You don’t see that many of them anymore. I look at something like The Sixth Sense, and that’s at its core a suspense movie, and so beautifully done. I’d love to see more movies like that.

It does feel like the genre’s fallen away a little bit with those mid-budget films. It’s all-or-nothing in Hollywood isn’t it?

You know, that might be one of the reasons they’ve disappeared, because it was very much a mid-budget kind of genre. Now you either have your micro-budget, Blumhouse model, which does fantastic work, I’m a big fan of what Jason Blum does, or you go straight to $90 million. The middle movie – especially that middle-budget human drama, without visual effects or action, really seems to have gone by the wayside. I’m hoping outlets like Netflix, Amazon and Apple really start to pick that up.

If those sorts of films do go to Netflix, will cinema just become the home of the big spectacle?

It seems more and more that cinema is leaning towards the big spectacle. But then you look at The Shape Of Water, which was a modestly budgeted movie. I think the studios really want the big franchises – that’s the big swing and the big money if you can hit it. And also, I think the success of Kevin Feige and Marvel has really influenced that thinking. Everybody wants to be Kevin Feige and Marvel, because they’ve figured it out. Every time they come out with a movie that’s spectacular… there’s never been a run like this.

So I think increasingly, you’re going to see more and more franchise movies. The middle ground of movies has already been squeezed out; right now it is mostly big franchises and smaller micro-budget movies. But yeah, it’s my absolute hope that Netflix and the other streaming services pick up that mantle, because you think about when I was growing up, all those movies like The French Connection – they just couldn’t get made today, and it’s a real shame.

Steven S De Knight, thank you very much.