Star Wars: 10 Unsung Heroes Behind A New Hope

Behind the story of the first Star Wars film is a group of talented artists and filmmakers that helped make the franchise what it's become.

This article first appeared on Den of Geek UK.

In theatres all over the world in 1977, audiences thrilled at the sights and sounds of Star Wars. Harking back to a bygone age of Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers, it also pointed forward to the coming age of ubiquitous computers and special effects-led blockbusters.

But while the triumphant fanfare of John Williams’ score gave Star Wars a confident swagger, its success was far from preordained. George Lucas reworked his script time and again studios turned his concept down, and even the production was rushed and torturous.

By now, the contribution George Lucas, John Williams and Star Wars‘ cast made to cinema is well documented. But what about some of the other artists, technicians, and fellow filmmakers who helped to make the movie such a success? Here’s a look at 10 unsung heroes behind Star Wars...

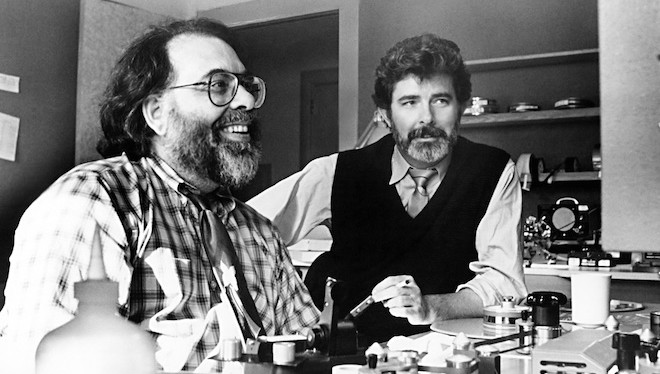

Francis Ford Coppola

George Lucas was still a film student when he befriended the up-and-coming director Francis Ford Coppola, who was then on the cusp of his 70s success with movies like Patton, The Godfather, and The Conversation. In many ways, Lucas and Coppola were total opposites – the book Easy Riders, Raging Bulls paints a portrait of an overbearing, brash Coppola with a talent for self-promotion, while Lucas is described as quiet and unassuming.

Nevertheless, the two became partners for many years. The pair even formed the independent film studio American Zoetrope in 1979. Lucas’s debut feature, THX 1138, was produced through the company. It wasn’t a huge hit, but Coppola continued to encourage Lucas to write and direct. “[Coppola] came to me and said, ‘no more of these experimental science-fiction robot movies,'” Lucas later recalled in an interview with Stephen Colbert. “‘I dare you to do a comedy.'”

That comedy was American Graffiti, a coming-of-age drama that, despite the misgivings of its distributor, Universal, became a colossal hit. Coppola was keen for Lucas to make Apocalypse Now after American Graffiti, and was slightly mystified that Lucas was so intent on making a film for 10-year-olds, as it was widely perceived, rather than a more respectable war film. But Lucas pressed on with his Star Wars script, somehow ignoring his own dissatisfaction and the bemused comments of his peers.

Despite Coppola’s misgivings over Star Wars, the pair remained friends. Lucas even took inspiration from Coppola when creating the character Han Solo. Imagine the Empire as Hollywood movie studios, and Han Solo becomes the loveable rogue filmmaker, “skating along the edge of the precipice,” as Easy Riders, Raging Bulls author Peter Biskind puts it.

Ralph McQuarrie

While Lucas spent many hours arranging his nascent ideas for Star Wars into a workable draft, he turned to illustrator and designer Ralph McQuarrie to come up with some early concept art. Even though he didn’t necessarily think that Star Wars would ever get made (“too expensive,” he said), McQuarrie liked Lucas’ sci-fi concept, and with his imagination fired up, he created a range of location and character designs which greatly influenced how the finished film would look. McQuarrie’s visuals for characters like R2-D2 and C3P0 are very similar to those that appeared in 1977, while the artist’s suggestion of giving Darth Vader his wheezing face mask would have a huge bearing on the villain’s screen presence.

When Lucas submitted his script to 20th Century Fox for approval, he provided copies of McQuarrie’s artwork. Without McQuarrie’s concepts, it’s possible that Star Wars would never have been given the greenlight. After Star Wars, his first film as a concept artist, McQuarrie worked on the two sequels and a string of other classic films, including Close Encounters of the Third Kind and Raiders of the Lost Ark.

Alan Ladd Jr.

When it came to trying to find backers for Star Wars, Lucas was famously met with blank faces all over Hollywood. Studio after studio, including Universal, United Artists, and Disney, were singularly unmoved by Lucas’ wide-eyed space fantasy. Finally, Lucas found a receptive mind in Alan Ladd Jr., a producer and head of 20th Century Fox.

Then still in his late 30s, Ladd (or “Laddie” as he was commonly referred to) was a little more open-minded than most of the older Hollywood moguls in power at the time, and impressed by Lucas and Ralph McQuarrie’s artwork, agreed to fund the project for a relatively small $8.25m.

Brian De Palma

There’s a legendary story that Lucas screened an early cut of Star Wars for a few of his Hollywood friends – among them John Milius, Steven Spielberg, and Brian De Palma. It did not go well. De Palma, in particular, was vocal about the rough cut’s failings, mocking its repeated references to the Force and its lengthy opening title crawl.

Nevertheless, De Palma proved something of a help to Lucas, that dismal screening aside. According to Dale Pollock’s book, Skywalking: The Life and Films of George Lucas, De Palma helped rewrite the opening text crawl, making it less verbose than Lucas’ earlier version.

“I showed the very first crawl to a bunch of friends of mine in the 1970s,” Lucas told the Chicago Sun-Times. “It went on for six paragraphs with four sentences each. Brian De Palma was there, and he threw his hands up in the air and said, ‘George, you’re out of your mind! Let me sit down and write this for you.’ He helped me chop it down into the form that exists today.”

Several months earlier, De Palma had also helped Lucas through Star Wars‘ casting process. De Palma was making Carrie at the time, and needed actors of a similar age to the ones Lucas was looking for. De Palma’s presence in the casting room allowed the more retiring Lucas to sit quietly rather than interview every candidate himself, and ultimately, several actors considered for Star Wars ended up in Carrie instead – such as William Katt, who was initially considered for the role of Han Solo but ended up playing Tommy Ross in De Palma’s movie.

John Barry and Roger Christian

Given just how tight money and time were during the production of Star Wars, what set designer John Barry and set decorator Roger Christian managed to achieve is remarkable. Barry came up with the unique look of Tatooine and the interior of the Death Star, while Christian came up with an ingenious means of building the interior of the Millennium Falcon – he used bits of scrapped aeroplane. As Christian told Esquire:

“I told George gingerly one day, ‘I cannot afford to dress these sets, I can’t get anything made in the studio,’ but my idea was to make it like a submarine interior. And if I bought airplane scrap and broke it down, I could stick it in the sets in specific ways — because there’s an order to doing it, it’s not just random. And that’s the art of it. I understood how to do that — engineering and all that stuff. So George said, ‘Yes, go do it.’ And airplane scrap at that time, nobody wanted it. There were junkyards full of it, because they sold it by weight. I could buy almost an entire plane for 50 pounds.”

As for John Barry, the author of Star Wars: The Blueprints, JW Rinzler, made the set designer’s contribution clear in an interview with FX Guide:

“Set designer John Barry and his crew really don’t get a lot of credit – they really did a lot of the sets from scratch. There was no concept art for any of Luke’s homestead stuff. That was all John Barry. The Rebel Blockade runner, as well. Ralph McQuarrie had done a painting but really these guys took it to a whole new level. The Death Star was actually John Barry’s design, even though McQuarrie did paintings, Barry talked to him about how to do it.”

The “used future” aesthetic may have been of Lucas’s devising, but Barry and Christian were responsible in no small part for the execution we saw on the big screen.

Fred Roos

Were it not for producer Fred Roos, Harrison Ford could have been remembered by history as Hollywood’s most accomplished carpenter. By 1976, Ford had largely given up on acting. Small parts in American Graffiti and Apocalypse Now (the latter not finished until 1979) failed to lead to more work. Meanwhile, Lucas was casting for Star Wars, and bringing in groups of actors to perform together in order to demonstrate their potential chemistry.

It was Fred Roos, a friend of Ford’s, who mentioned to Lucas that Ford was available, but Lucas was reluctant to have an actor who’d appeared in American Graffiti feature in Star Wars. Instead, Lucas had Ford simply perform line readings for the other actors brought in to audition. Gradually, it dawned on Lucas that Ford, the actor feeding lines to other, less interesting actors, might be the right guy to play Han Solo after all…

Stuart Freeborn

Make-up artist Stuart Freeborn’s greatest contribution to the Star Wars franchise wouldn’t come until The Empire Strikes Back, where he famously created Yoda by sculpting a mischievous, wise face which shared some of his own features and those of Albert Einstein. Before that, Freeborn played a pivotal role in bringing some of Star Wars‘ pivotal characters to life. He made Chewbacca. He created the freakish aliens crowded into the Mos Eisley Cantina – a job so intensive that he had to bring in his wife and son (who were also make-up artists) to help him out. For Return of the Jedi, Freeborn created the gigantic, loathsome Jabba the Hutt – arguably one of the most memorable characters in that film.

John Mollo

Costume designer John Mollo was previously a specialist in military uniforms, having previously worked on the outfits for such films as Zulu Dawn and Stanley Kubrick’s glacial period piece, Barry Lyndon. Star Wars was therefore Mollo’s first film as a costume designer, and the ingenuity of his work led to a long and successful career in a range of high-profile films, including Alien, Gandhi, and Chaplin.

Working closely with Lucas several months before production began, Mollo helped devise an ingenious color scheme for Star Wars, which saw the villains decked out in greys and blacks, while the rebels wore earthy, natural colours like browns and oranges. You can see his interest in military uniforms coming through everywhere , from the tunics worn by Grand Moff Tarkin and the other starched-collar baddies aboard the Death Star, to the armour and helmets of the Empire’s assorted Stormtroopers, TIE pilots, gunners, and fleet troopers.

Ben Burtt

So much of Star Wars‘ brilliance lies in its sound. We only have to hear the hum of a lightsaber, the roar of a TIE Fighter, or a plaintive groan from Chewbacca, and we’re transported back to its exotic sci-fi universe. Those sounds are all thanks in large part to Ben Burtt, who had a penchant for mixing unlikely noises to create something entirely new.

That lightsaber sound? A combination of a whirring film projector and dying television set. Those roaring TIE Fighter engines? A mix of slowed-down elephant and car tires rushing along a wet road. Chewbacca’s vocalizations? A blend of bear, walrus, lion, and dog. Those sounds and more helped drive Star Wars to its global success, and marked the start of Burtt’s continued presence in the franchise – he’s made cameo appearances in subsequent films and returned as sound designer on The Force Awakens.

Marcia Lucas

George’s wife from 1969 to 1983, Marcia Lucas’ influence on American Graffiti and the Star Wars trilogy was profound. Although Marcia Lucas was nominated (along with Verna Fields) for an Oscar for her editing work on American Graffiti, Marcia wasn’t originally working on Star Wars in the late 70s. While George labored on his space opera, Marcia worked with Martin Scorsese on Taxi Driver. But as production on Star Wars wound on, Lucas realised that the editor he’d originally hired (John Jympson) wasn’t cutting the film together with enough creative verve.

Jympson was duly replaced by three new editors, Paul Hirsch, Richard Chew, and Marcia Lucas. Together, they took Star Wars to pieces and put it back together in a way that conveyed the pace the story clearly required. One of the key sequences Marcia worked on was the final assault on the Death Star. Knowing that it was one of the pivotal moments in the movie, she took it apart and re-ordered the scenes to give it a greater flow and build-up.

Marcia and George’s subsequent break-up has often left her overlooked, but her contribution to the Star Wars franchise shouldn’t be underestimated. While she shared an Oscar with Hirsch and Chew for her editing work, Marcia’s efforts went beyond the technical. For years, she was George’s closest and most honest critic, telling him frankly which parts of his story worked and which ones didn’t. When George struggled with what to do with Obi Wan Kenobi’s character towards the end of Star Wars, it was Marcia who came up with the idea of killing him off. Conversely, Marcia encouraged George to keep some of Star Wars‘ more humane moments, too. Leia’s “Kiss me for good luck” line to Luke was nearly edited out, until Marcia convinced him to leave it in.

Michael Kaminski wrote an exhaustive, brilliant essay about Marcia Lucas’ contribution to Star Wars (you can find an archive of it here). It’s essential reading, and an important reminder that movie history could have been very different without Marcia’s input.

Honorable mentions:

Gary Kurtz, the producer who helped convince FOX to loosen their purse strings just enough to get Star Wars made (including an additional $50,000 for a last-minute set-build).

John Dykstra, the special effects supervisor at the newly-minted ILM. Lucas and Dykstra later fell out, but Dykstra and his team won an Oscar for their ground-breaking achievements.

Gilbert Taylor, the cinematographer who gave us some of the most distinctive and memorable shots in American movie history.

This article first ran on April 23rd, 2015.