Saw X Tries to Change How You See Jigsaw (and Fails)

John Kramer is more heroic than ever in Saw X, but that may not be a good thing.

John Kramer doesn’t like what he sees. After another disappointing doctor’s visit, the one-time villain of the Saw franchise, Jigsaw, pauses outside a patient’s room in order to have a drink of water. There he spies a custodian (Isan Beomhyun Lee) rifling through the belongings of that patient. The camera holds on Kramer’s eye staring at the custodian’s dirty deed before suddenly hard cutting to a shot of that same custodian, now in a trap. For this game, the custodian must turn a dial and break each of his “sticky” fingers, one by one, or have his eyeballs sucked out via an intensified version of the vacuum he uses.

As we soon learn, this first trap introduced in the weekend’s Saw X is actually a fake out; a figment of Kramer’s imagination as he thinks about the custodian’s actions. The scene ends by flashing again to the present where the custodian sees Kramer, played again by the excellent Tobin Bell and puts back the stuff he took. “Good choice,” growls Kramer.

The scene also disappoints us viewers, and not just because it’s one of the rare fake outs in a series that plays the gore straight, even if it also plays fast and loose with narrative continuity. Rather, it disappoints because we wanted to see the custodian get punished for his sins. We watched John Kramer mete out justice to one who deserved punishment. And we liked what we saw.

It’s fitting that Lionsgate Entertainment chose the eyeball trap as the poster image for Saw X. It sets the tone for the latest entry in the franchise, one that doesn’t so much as throwback to the heydays of Saw as much as it refocuses the story. Saw X isn’t about Dr. Lawrence Gordon (Cary Elwes) or Jeff Denlon (Angus McFaydan), regular folks who wake up in a torture game and are forced to learn a lesson. No, Saw X is about John Kramer himself, as the man called Jigsaw moves from the shadows of convoluted continuity to become the hero of his story.

The Angry Appeal of the Saw Movies

John Kramer has always seen himself as a hero. Even in the original Saw of 2004, long before we learned about his suicide attempt, his wife’s miscarriage, or the scam depicted in Saw X, Kramer presented himself as a man with extreme self-help philosophies. That’s only grown over the course of the franchise, to the point that Kramer can declare in Saw III, “I’ve never killed anyone and I despise murderers.”

Through most of those entries, however, the audience is encouraged to stay on the side of the victims. Even those who did objectively terrible things, like killing a kid while driving drunk or burning a building for insurance money; even when we shouted in delight at the gory deaths on screen, we never really sided with Jigsaw’s philosophy. Throughout it all, Kramer came off just as deranged as his many apprentices, a guy whose lack of proportion justified the torture of drug addicts, battered wives, suicide survivors, and other victims.

It can be argued that the relationship between the popularity of the movies and the evil of John Kramer stemmed in part from America’s role on the global stage during the 2000s; the heyday of the Saw franchise. In his book Torture Porn in the Wake of 9/11, San Fransisco State University Professor Aaron Michael Kerner declared, “The genre of torture porn— a brand of horror film that emerged in the wake of 9/11 and the War on Terror— attempts to negotiate the angst-filled years colored by the devastating terrorist attack.”

According to Kerner and others, torture porn flicks like Saw help Americans (and their allies, as is the case with Saw’s Australian creators, James Wan and Leigh Whannell) to make sense of torture as a moral good against evil terrorists. The religious jargon of the Bush administration echoed in the messages Kramer sent his contestants. Kerner sees in Kramer’s use of accomplices an echo of the U.S. using private military groups to do its dirty work overseas.

Thus when the first audiences watched Saw and its sequels, they thrilled at the gore, but they also felt more than a little guilty about their participation in the spectacle. They turned their mistrust toward Kramer, a man who, like the U.S. itself, turned a wrong against him into an excuse to spread suffering to others.

The Heroism of John Kramer

But then something funny happened on the way to later sequels. Jigsaw became a hero. It’s not entirely unusual for a killer to become the fan favorite in a horror franchise. Over time Freddy, Chucky, and Jason have all become the main attractions of their stories, with Robert Englund, Brad Dourif, and Kane Hodder winning more sympathy than whatever underdeveloped character they’re offing onscreen.

Kramer’s ascendency to main character status happened as the police plots of the first five movies ran out of steam, forcing writers Patrick Melton and Marcus Dunstan, who took over from Whannell after Saw III, to come up with a new modus operandi. So in Saw VI, Jigsaw tortures not a doctor who needs to pay attention to his family, nor a father who needs to move past his son’s death. He tortures an insurance executive who puts profits over people.

The A-plot of Saw VI follows a game designed for William Eaton (Peter Outerbridge), president of Umbrella Insurance Company. Eaton uses his own special algorithm to determine who receives help and who does not, thereby ensuring profits for the company. That algorithm drove Eaton to deny Kramer’s request to participate in a radical Norwegian cancer treatment. It also convinced him to deny help for client Harold Abbott (George Newbern), who died and left behind his wife Tara (Shauna MacDonald) and son Brent (Devon Bostick).

As Eaton goes through his game, killing other members of the Umbrella staff in the process, Saw VI director Kevin Greutert keeps cutting back to Tara and Brent’s perspectives. In the final moments, when the Abbotts decide to let Eaton die, they do so with a righteousness the audience endorses. The audience sees Jigsaw killing bad people who have hurt others—others just like them.

Jigsaw’s Hero Turn in Saw X

Although set between Saw and Saw II, Saw X once again focuses on the medical world. Returning director Greutert, joined now by writers Pete Goldfinger and Josh Stolberg, follows Kramer’s attempt to undergo the experimental procedure he pitched to Eaton in Saw VI.

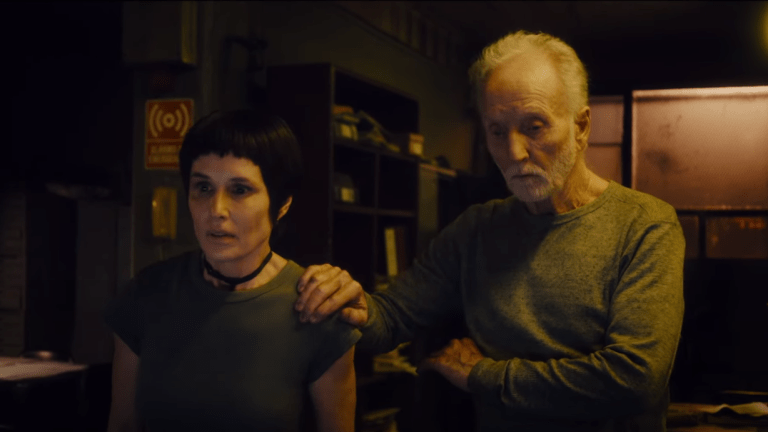

After paying vast sums of money to Dr. Cecilia Pederson (Synnøve Macody Lund), the supposed daughter of the man who came up with the procedure, Kramer discovers that he has been scammed and left to die in Mexico City. With the help of his assistants Amanda Young (Shawnee Smith) and Mark Hoffman (Costas Mandylor), Kramer exacts revenge against Cecila and her cohorts by forcing them to play grisly games.

On the surface, that description doesn’t sound too different from plots in previous Saw movies. After all, Kramer has used his traps against people who have personally wronged him, such as Dr. Gordon or Mitch, the young man who sold a faulty motorbike and caused the death of Kramer’s nephew. However, previous entries began with the victims in the traps, letting us see them as humans in horrible situations before revealing their relationship to Kramer through flashbacks. As a result, we see Kramer’s method not as justice, but as a horrid overreaction; a self-righteous excuse to inflict suffering.

Saw X breaks that mold. It begins with Kramer at his most weak, inside an MRI machine, and stays with him as he endures indignities from disinterested doctors. We watch hope fill Kramer’s eyes when he sees Henry Kessler (Michael Beach), a fellow terminal patient who claims to have been healed by Pederson. We see that hope turn to bitterness when he realizes that Kessler was a plant, part of the larger scam.

The Dangerous Game of Saw X

By making Jigsaw the main character, Saw X inverts the moral compass of the franchise. With the War on Terror a bad memory for most Americans, many of us feel like we don’t have to worry about the reality of actual suffering of actual other people. Instead we can focus on our own suffering, something many Americans have experienced at the hands of a medical industry more byzantine than the Saw franchise’s plot structure.

In Saw X, the victims deserve their punishment. They did the unthinkable and rarely show real remorse, even when forced to break their own bones to avoid radiation poisoning. For that reason, we want to see them suffer. We want to see Kramer succeed.

Like Amanda and Thompson, we viewers are invited to become Kramer’s newest acolytes, people who are indoctrinated to use our own sense of suffering to inflict or enjoy the suffering of others. Along the way, we become interchangeable with the torturers of the first movie: pigheaded abductors and glowering puppets, all in search of gory, self-righteous revenge.