Roger Donaldson interview: Sleeping Dogs, Costner, Statham, digital filmmaking and more

Roger Donaldson chats to us about Sleeping Dogs, The Bank Job, Thirteen Days, Cocktail, Dante's Peak, No Way Out and much, much more...

Over 40 years since he made it, Roger Donaldson’s first cinematically-released feature film – Sleeping Dogs – is getting a gleaming new Blu-ray release. I got to chat to him about it, and also look across his career. Given that his extensive, impressive directorial CV consists two brilliant Costner movies and a slice of vintage Jason Statham, we had a lot to talk about.

And here’s how it all went…

I found myself growing up with a lot of your films, but had never seen Sleeping Dogs, your debut film feature, until this week.

How do you feel now looking back at it as a first feature? Different filmmakers seem to split between either ‘if I’d known what I know now’ and ‘I never felt more in control than I was on my first film’. What are your thoughts?

I’d made a number of documentaries by the time I came to it, so I went into it thinking I could pull it off. But I also went into it with an ignorance of what the job really entailed, because doing a feature film is much more demanding! A very different undertaking.

I was producing it as well, so I was involved in raising the money, and spending the money! The dramas that came along as a result of not having enough money. You never have enough money of course, but I didn’t realise what ‘enough money’ meant!

Can you give me an example?

Yeah. There’s a sequence where the guys are escaping in an old Zephyr. We had one car! On the rehearsal, the stunt guy who had never really been a stunt guy before, loses control of it on a corner and ploughs the car into a bank. And writes the front of the car off! That’s the car for the sequence we’d got that day.

Someone said ‘I’m sure I saw a car like it driving down the road an hour ago’. This was a rare car anyway in New Zealand, so the thought that there was another car like it within an hour of us was pretty preposterous. But we had to follow it up. The production manager went around the crew and got $5000 out of people’s pockets, and took off flat out down the road on the only way out of town. He caught up with this guy, and persuaded him at the side of the road to sell his car! And he came back an hour later with it.

We still had to get our day of course, in a limited time frame. Those are the kind of dramas that you face in your first film. You can’t factor in what’ll happen, but you have to go with the flow when it does!

I’ve always got a sense from your work that you enjoy problem solving on a film set.

I do, yeah. That’s very true.

You’ve talked in the past, for instance, about cranking a camera speed for Splash Palace, and using massive rear projection in The Recruit. Practical challenges appeal?

They do, yeah. I think the fun of being a director on a movie is first of all, you don’t make a film on your own. You work with a great bunch of like minded people, who believe in the film as much as you do. As director, you get to take control and say how it’s going to go. But without the support of those people, you’re nothing.

I went through the later making of documentary on the Sleeping Dogs Blu-ray, and there seemed an admission from the people making the film that you didn’t quite know what you were doing…

I think that’s true!

That you were all mucking in. And that you were a director who could do everything, and to a point, tried to.

Well, I didn’t want to do everybody’s job! But as a filmmaker, I started out as a cinematographer myself, and as a cinematographer, I pulled my own focus. I edited my own materials. I had to run around being the art director on commercials, and stuff like that. I did come to it with a deep knowledge of what it took to do the job. I wasn’t going in trying to do people’s jobs uneducated.

But there’s Geoff Murphy [who’s gone on to direct films such as Young Guns 2 and Fortress 2], a crusty character in his own right, and he was the special effects guy solving problems. You weren’t allowed to have weapons in New Zealand, so all the guns had to be made. The way they fired was with matchheads. He was an incredible problem solver.

You bring Geoff Murphy up, and when you came to do a huge Hollywood movie – Dante’s Peak – you hired him to do effects and second unit work on that. Was it a kinship? Problem solving in the trenches between the two of you?

Yeah. Geoff and I have been friends since one of the very first films I made. It was about counter-culture and hippies in New Zealand, and that’s when I first met him! Him and his band of hippie mates! They built this dome for the movie. He was a school teacher, and a trumpet player in a jazz band!

You’ve talked about wanting to make a film with 30 friends, rather than 30 enemies.

Yeah. It’s often very hard to get people who worked with you on one film onto the next, but in some cases… composer Peter Robinson has done five of my movies, Andrzej Bartkowiak, my DP, I think we did three movies, now he’s directing his own.

It’s inevitable to draw a contemporary alignment with Sleeping Dogs. I found an interview you gave in 1977 where you said of the film’s release that “there are people who are prepared to have total disregard for the rights of individuals, people who feel that the end justifies the means’”. It’s hard not to draw a modern day parallel there.

Yeah. I think that’s one reason why that film has survived. A movie comes out, and when this one came out it was a big deal in New Zealand for very different reasons. It was the first colour feature film made in New Zealand. It was ambitious in its scale. It came at a time when New Zealand was discovering its cultural heritage, and wanted to escape a little from the bonds of England and the US in terms of its cultural identity.

Now, of course, it’s looked at in the light of fascism, totalitarianism. What’s happening in the world today.

A simple question maybe. But I live thousands of miles away from where Sleeping Dogs was made. In the UK, 40 years after its initial release, it’s getting a gleaming special edition Blu-ray release. For a $150,000 film made on the other side of the planet four decades ago. How does that feel?

Well, I have to tell you it makes me feel pretty damn good!

I saw it recently, and someone said to me that history judges your work far more accurately than what happens at the time. That film was done with a total passion. It was representative of New Zealand at a very particular time in its history. It led to the creation of the New Zealand Film Commission, and there are a lot of thing about it that are historically very important. But I think the film is still relevant to this day!

Evidently so! But it’s strange isn’t it? If we were doing an interview about a blockbuster you’d made that was coming out tomorrow, the talk would be to a degree about box office.

Yeah.

And yet your films are continually being revisited for special edition discs.

I did a voiceover the other day, actually. A commentary for a new version of Cadillac Man that’s coming out.

There was a film that the audience just didn’t seem ready for. A dark Robin Williams movie in 1990.

No, I think so. And of course, Robin Williams’ demise, there’s a way of looking at Robin’s work in a different light now to when Cadillac Man came out.

On another of your 90s films. I got talking about you when Willem Dafoe came to the UK last year to do some promotional work.

Willem’s a great guy!

Well, we ended up talking about you, and about the film you made with him, White Sands.

I loved making that film.

Oddly, he said exactly the same thing. He said ‘every day on that one, I loved coming to work’. That was the same for you?

Yes.

I ask because I’m always struck by Steven Soderbergh’s comments on directing Ocean’s 11, where he talked about the cast all having a great time making the film, but that for him, it was bloody hard work!

I liked Willem a lot! I think he’s a very talented actor, and he got my vote this year at the Academy Awards [for The Florida Project]. There was something about New Mexico and Santa Fe and the White Sands area. It was visually such an interesting place to be, and I had a great time making it.

But you love outdoors?

I do. I do love the outdoors.

Going back to solving problems on set. How does that transfer when you move to productions that are more effects-driven? You always stuck mainly to practical effects, but how you’d approach Dante’s Peak and Species today, for instance, would be very different?

Yeah. Both of those films had digital elements in them, and it was the very beginning of motion capture. Taking digital elements and blending them with real images. Part of the reasons I did those films is I saw the future coming. That digital was going to have such an enormous impact on filmmaking, as it’s had, that I wanted to be at the forefront of what was happening. I was faced with the infancy of these technologies, and so stuff I thought would work didn’t work as well as I thought it would. Making digital figures stick to the background, issues like that. I was forced to fall back on doing stuff for real in both of those movies than I was expecting to do.

Conversely, though, do you think it’d be less fun to do now, with digital tools that instantly solve those problems?

I will never have as much fun making a movie as I did on those big ones. Dante’s Peak and Thirteen Days: they were really films that aren’t going to get made that same way.

No Way Out was the first of your films I saw. It was put out on the BBC as a Christmas season movie, back when that was a big thing. It was about the most risqué thing that’d put out at Christmas I think at the time!

[Laughs]

Without giving it away, though, can you talk about keeping the ending of the movie under wraps? Because today, that’d be blabbed about within minutes.

I know, I know. People really did respect the end of that film, and didn’t divulge it. For some reason people just said ‘I can’t tell you how the film ends’, and they didn’t!

Did you foresee that it might be a problem? Were you worried?

I don’t remember being worried, but I do remember hoping that the end would be the surprise that it was.

It was a film that followed your knack of working with big names just as they were breaking through too, Kevin Costner in this case.

I have been very lucky! Part of it is good luck, and part to good instinct.

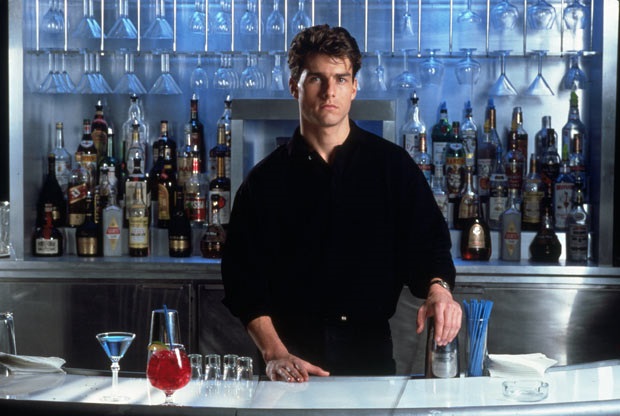

Luck is an interesting factor. Looking at something like Cocktail, there was an article in Premiere magazine around the time that film was coming out, where it reported that then-Disney movie boss Jeffrey Katzenberg was having kittens over the title, and tried to change it at the last minute.

That’s a great example of history being kind to the movie.

At the time it came out, it was probably one of the most popular films I’ve ever made. At the time, because it was Tom Cruise and about youth and drinking, and stuff like that, there were a lot of harsh comments about it. But in the history of filmmaking and what was important in the 80s, and what was representative of the 80s, that film has got a reputation. People are still talking about it, and the fact that they still are suggests it connected with people. I meet people who can recite the whole script of that movie. I couldn’t give you five words out of it!

The generation that went and saw that film, it seemed to be a memorable part of their growing up.

I only saw it myself for the first time a year or two back, in truth, and didn’t appreciate what a dark story it is.

It is a dark story.

Very much. I also didn’t appreciate it won Golden Raspberry Awards – an awards ceremony I hate – but I wonder what being in the midst of all of that was like?

Ah, if you’re successful, there’s always an element of people wanting you to fall from grace.

Tom had made Top Gun, and the movie was incredibly successful. And Tom’s charming smile, he’s too good to be true in some ways and still is, and there was an element of the critical media who felt their job was to put the opposite point of view to the audience. But as an artist, that’s what you’ve got to take. Nobody gets away unscathed. If you’re prepared to put your work on screen, you have to accept that you’re not going to connect with everybody.

You’re saying that now though with the hindsight of years that have passed.

Yeah, yeah.

But doesn’t it sting at the time?

When it came out, it was the number one film that week. It was the highest grossing film that Disney had for an opening weekend. There were a lot of positive things happening from the business side. But also, was it going to have legs, and were people going to continue to see it? Was it going to be successful? The longer it goes, the more successful it proves to be!

It’s not a bad problem to have, is it?

No [laughs].

Rewinding slightly, your big Hollywood breakthrough movie was actually going to be Conan The Barbarian 2 once upon a time, that you were hired to write and possibly direct. But how close did that actually come to happening?

Here’s the history of what happened there.

I’d made a film called Smash Palace, that got noticed by critics over here like Roger Ebert and Charles Champlin. Those heavyweight critics of America. They had seen it at the Cannes Film Festival where it was in the market. The first screening there were a few people. The next screening was packed. The third you couldn’t get into it. It was the discovery of that year’s Cannes Film Festival.

The reviews came out, the people in the business – the lawyers, the agents. Harry Ufland, who represented Martin Scorsese and Robert De Niro said he wanted to represent me, and did represent me. David Brown and Richard Zanuck, famous film producers, got me to come over to the States and work on a project for Fox that they were doing. I came over to the States, the film got put into turnaround. And there I was. I’d made the move over here assuming the film was going to happen, and I was unemployed in Los Angeles with a young family.

I ran into Ed Pressman, whose work I’d loved. Ed told me he was doing a sequel to Conan, and asked if I’d be interested in writing the script and directing the movie. And it was a pretty short thought process: I said yes!

Then what happened?

I got Ian Mune to come over to work on The Bounty, and we sat down and wrote a sequel to the Conan script. Towards the end of the writing process, Dino De Laurentiis bought the rights to Conan from Ed Pressman. I went to a meeting at the Beverly Hills Hotel. I met Dino, and he had this script with him. And he said “Hey Roger, why are you making this, it’s 270 pages long?”

I was like, what? Let me see that?! And the script had been translated into Italian, and was now 270 pages long! I said to Dino, that’s not the script I wrote!

It was a meeting that didn’t go anywhere, and the next morning at 5am, the phone rang. It was Dino. I picked up the phone in the dark and have it the wrong way around. I hear this distance voice going “Donald, Donald”, which is what he always called me. “Dino here!”

He told me to go immediately to the Beverly Hills Hotel, still at five in the morning! I got out of bed, got dressed, went to the hotel, Dino makes me a coffee. He says “Why do you want to make Conan?”. I told him I needed a job. He said “Donald, you don’t want to make this piece of shit. You want to make a good movie. I’ve got this movie called The Bounty”.

I said I thought David Lean was doing that? He said “No, he’s gone, he’s history, will you make the film?” I said I haven’t read the script, he says “I’m going to Mexico today to visit the set of Dune. You can call me on this number on the plane and tell me if you’re going to do it. You’ve got until midday”.

I didn’t have to really read it to say I was going to do it, though, as I just needed a job. I did know the story, but by midday I say I’m interested. He said “Come to New York tomorrow. Get on the plane today, I’ll meet you for breakfast tomorrow, and we’ll talk about the deal”.

And you did?

I get to New York, and there I am sitting in front of Dino. And he says to me “How much do you want to do this movie?”. I said Dino, you’ve got to talk to Harry Ufland about that. He said “You tell me now or get out of my office”.So I went shit, what do I do? I knew the prices I was being quoted at, I knew he was going to beat me up whatever the price is. So I thought I’ve got to double it. I took a deep breath and did that, and he goes “Oh, I’ll give you nearly that”.

The next day I was off to England to start prepping the movie!

Just talking about some of those names: that 15 year period when you were making Hollywood films. You were right in the transition from filmmakers running studios to accountants running studios.

Yeah. Mike Medavoy at Orion, he was someone who really believed in the filmmaker. Working for someone like him was great.

Did you feel the change?

I think as the studios got bought by big conglomerate companies, where film divisions were part of their lesser entities, the filmmaking companies because more show business than show art.

No Way Out comes out, then, and is the movie it is. Did you feel that was a turning point?

No, I think The Bounty was the big change for me. I got an amazing collection of actors in it, who are still legendary today. It was at the beginning of their careers too. I sort of fell on my feet a little when I came to Hollywood, although it wasn’t clear sailing. I definitely had lots of opportunities to do different stuff.

I’ve held off talking about my favourite of your films, but I think it’s time! Thirteen Days, then. You made it at New Line at a point where it was very much backing filmmakers with risky projects. Paul Thomas Anderson with Magnolia springs to mind, Dark City.

Their biggest film was the thing they were doing with Peter Jackson at the time! That’s where their resources were going!

Were they raiding budgets to make Lord Of The Rings, and did that affect you?

I didn’t get raided to make the film, no. But I did when it came to be released. They were definitely focused on Lord Of The Rings and not Thirteen Days. Both financially and how they went about releasing.

It’s such a film, though. I took my dad to see that and we were blown away for slightly different reasons.

For me it was something going back to my teenage years. I was a teenager at the time [the Cuban Missile crisis] happened, and I happened to keep a diary. In my diary is reference to what was happening. Will I wake up tomorrow and be in a thermonuclear war?

My dad walked out of that film – and we never saw too many films together – he said it was brilliant, but that the only thing that was wrong was John F Kennedy would have had sex with half of the room by the time the first hour was up.

[Laughs] That’s probably true!

You were reunited with Kevin Costner for it of course, but the Kevin Costner you were working with on Thirteen Days – in terms of stature within the Hollywood system – was very different to the one you worked on with No Way Out.

I mean, Dances With Wolves [had happened], a fantastic movie, some of Kevin’s best work.

It was really Kevin who got me into Thirteen Days. He was there before I was there. He was friends with Armyan Bernstein and they were going to make the film. He supported me being the director of it.

Did he consider directing the film himself?

I’m sure he did, I’m sure he did.

I love – and this is common to a lot of your films, and it’s strange sometimes that this is seen as a criticism – that there’s no fuss to the storytelling. Thirteen Days really, really benefits from that.

Here’s one of my things as a cinemagoer. I hate it when the seat gets hard, and I start looking at my watch. You’re there to take the audience to a place that they’re not going to go even sitting in front of their TV set. There’s something about sitting in the dark with a lot of other people, in front of a big screen. You get completely absorbed in the story, if it’s working. Nothing annoys me more than me starting to get distracted.

I try to make my films very succinct and to the point, and not overly indulgent.

Would you say a lot of your films changed dramatically in the edit?

No, I wouldn’t say so. I tried to make them as tight as I can be, and when I look at some of my older films, I do think if I went back and cut them I could improve them!

Does that come down to you being such an on-set problem solver again then? There’s a quote on the Sleeping Dogs documentary that you leave it as late as possible to make a decision.

I do, that’s true. One of the things of course is if you’re doing big special effects movies, or stuff with complicated things that need to happen, then you have to storyboard it out. But if you’re talking with a bunch of actors about being in a room, you don’t usually get the actors before you’re shooting. So I like to go on the set with the actors, work it out with them, make the most of the room, and then bring in the DP and look at how we’re going to cover this. It’s leaving it to the very last minute, making decisions about how you’re going to shoot it.

That said, you’ve got to a vision of where it fits into the story. You’re never shooting in sequence, so as a director, you need to know where a performance should sit, and the timing of it, the suspense. So yeah, I do try and leave it late. Not because I’m not prepared to do it earlier, but the more time I have to think about things, the better is going to be.

And that’s the real fun?

Yeah, it is fun. It’s very collaborative, too. To give an actor like Kevin… he has strong opinions of his own. It becomes a collaborative process for how to stage it.

We chat to lots of people for our site about Jason Statham, and we regularly ask our interviewees what their favourite Jason Statham film is.

The Bank Job is mine [laughs].

It always comes up! It’s a very migratory film in his career, where he was perceived as an action star, and this was the film where he headlined and powered an ensemble cast.

Yeah, yeah.

Were you conscious that one of your lead performers was going out a little on this one?

Well, first of all, I thought that Jason was 100% perfect for the role. He fitted it perfectly, He’s a very charismatic actor, I really, really enjoyed working with him. He gives it everything. I love London too: I’ve done two films in London and enjoyed them both.

Working on that film with Jason was a lot of fun. And hard work, too. It was a fun story to tell, though. I put a lot of effort into researching it, and tried to get as much stuff into it as I could pack into it, while making an entertaining movie.

And you shot it digitally of course.

When I did The Bank Job it was the infancy of digital filmmaking.

It was a deliberate decision, because I was doing a lot of still work, and saw the difference digital could make. This was the future of the film world. It was clear to me that unless you understood this medium and got with it, you were going to be left in the dust. And I think history has proved me right. Last film I did I even shot someone in 4K on an iPhone, and you wouldn’t be able to tell what shot was from what camera in the movie.

One aside, I’ve always been curious about, not least because of your working relationship with Pierce Brosnan. Were you ever approached for a Bond movie?

I was actually!

I did wonder…

Without going into detail, the real reason it wasn’t going to happen was the deal wasn’t going to work. I did have meetings with them for one of the Bonds, and would have loved to have done one. My dad was a complete Bond fan. He loved Bond. Amazing how your parents can influence what you do! I’d have loved to have been able to have a Bond on my belt just to say dad, come and watch this one.

It probably was a two way street. They figured they couldn’t afford this guy!

What’s next then? The Guinea Pig Club?

I don’t know yet! It’s a possibility, though.

You had a sci-fi movie you were developing too?

There’s 20 at least that I’m working on [laughs]. You just have to keep going until one comes out the other end!

Roger Donaldson, thank you very much!