How Pleasantville Explores Fandom, Nostalgia and Identity

Pleasantville is a big-screen treatment of small screen nostalgia, and it's a movie that deserves more attention.

This article comes from Den of Geek UK.

This feature contains spoilers for Pleasantville.

When Gary Ross’ Pleasantville was released on DVD in the UK, its cover bore a Total Film review pull-quote labelling it as “The Truman Show meets Back to the Future.” It’s the kind of description that sounds bang-on but doesn’t actually do the film any favors. Judging by the numbers, it certainly didn’t help its box office performance at the time. Scanning more like a feature-length Twilight Zone story than a knockabout fantasy comedy, this technically brilliant film weaves an interesting teen movie-cum-civil rights drama around a fictional 1950s sitcom called Pleasantville.

In the film, high-schooler David (Tobey Maguire) is a child of divorce and a devoted Pleasantville geek, who clearly enjoys retreating into the uncomplicated exploits that the quaint and inoffensive program represents. On the eve of a big-money trivia challenge, David’s twin sister Jennifer (Reese Witherspoon) wants to watch a concert on MTV instead. When they break the TV remote in their ensuing row, a mysterious repairman (Don Knotts) comes along and propels them both into the black-and-white world depicted in the show.

Out of this fairly standard magical realism setup, Ross’ script aims higher with its central themes. Standing in for existing characters Bud and Mary Sue, David and Jennifer find that their very presence in the thinly sketched town begins to inexorably strip away its innocence, revealing things like sex and books, and even rainstorms to the fictional residents. As soon as parts of the monochrome environment start turning to Technicolor, certain characters begin a battle to preserve the town’s pleasantness.

Twenty years on, Pleasantville is something of an underrated gem. For one thing, it has an enviable cast, many of whom were right on the cusp of stardom. Maguire is every inch The Boy Who Would Be Peter Parker here, and Witherspoon was just a year away from a major breakthrough in Election. Then there’s a never-more-adorable Paul Walker in his screen debut as Skip, the clueless captain of the school’s undefeated basketball team. And that’s without even mentioning William H. Macy, Joan Allen, J.T. Walsh, and Jeff Daniels.

Though it was somewhat overshadowed by The Truman Show at the time, it’s also got a thoughtful, genre-bending script that feels more relevant today than it did back in 1998. From its unsubtle yet effective central metaphor to its ground-breaking visual effects, there’s plenty to look back on fondly. And yet, at its heart, it is a film about the perils of uncomplicated nostalgia.

In Living Color

Earlier in the 1990s, Steven Spielberg memorably played with color to make a young girl’s red coat stand out in the otherwise black and white Schindler’s List, and in the 2000s, Robert Rodriguez achieved the same effect on a digital backlot. Slap bang in the middle of these two, Pleasantville was the first film to use this style throughout its running time, and as an integral part of its storytelling.

Up until the release of Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace in the following summer, it had the most digital effects shots of any film ever released. Filmed entirely in color on 35mm film, it was then digitized at 2K resolution and color-corrected in post-production, enabling the mix of black and white and color photography seen throughout the film.

further reading: Why The Princess Bride is a Perfect Fantasy Movie

This digital colorization was a more technically apt solution than the hand colorization techniques that drew controversy throughout the 1980s when media mogul Ted Turner commissioned colored make-overs of classic films to be shown on his TV channels. Orson Welles famously appealed against Citizen Kane getting this disservice, saying, “Don’t let Ted Turner deface my movie with his crayons.”

What marks Pleasantville apart from other experiments with black and white and color is that the characters can tell the difference. They know they’re becoming more colorful, and some of them are unhappy about it. In this case, the question of preservation vs. expression is a social debate, as well as an artistic one, as Ross ties the idea of technological advances to ideological ones.

Continuity Errors

Unlike The Truman Show, what the characters don’t know is that they’re in a TV show. The film never broaches the subject of “the real world,” (or “Outside Pleasantville” as Jennifer terms it to her baffled geography class) as the characters grapple with their own small-town reality. When Marty McFly arrives in 1955 in Back to the Future, he’s mistaken for an alien and plays on that again later on in the film, but to everyone in Pleasantville, it just seems like “Bud” and “Mary-Sue” have started acting differently.

Alternately viewing it as either a dream or a nightmare, David and Jennifer each cope with their situation pretty well, under the circumstances. Neither of the twins is really climbing up the walls saying, “let me out, let me out,” but they have different reasons to engage.

With his fearsome trivia knowledge, David knows the ropes and starts out by largely going about with what’s expected of his character. As a more sexually awakened 1990s teen, Jennifer is immediately a more disruptive force. From asking perfectly innocent questions to gleefully introducing Skip to his own penis, she’s a walking anachronism.

Playing the gatekeeper, David is initially mortified by the continuity errors that ensue. It’s unheard of for any of the boys on the basketball team to miss a shot, but it starts to happen once the rules of the TV show are broken.

The crucial difference early in the film is that Jennifer is taking the people she meets as people, whereas David continues to see them as characters. Weird as it is that they’re both living inside a sitcom, this is his thing that his sister is encroaching upon and changing in unwanted ways. Looking back at it 20 years on, next to the current prominence of online fan communities and their popular complaints, it’s uncanny how even Jennifer’s essayed character is called Mary-Sue.

When we see David earlier, he’s lording his knowledge over a fellow fan, but also shyly imagining the conversation he would have with a girl while she’s standing 50 feet away talking to someone else. By planting him in the town of his dreams, the film gives David the role of gatekeeper for the thing he loves, but as a teen movie with a great big metaphor at its heart, it also forces him to emotionally mature.

further reading – The Purple Rose of Cairo: A Masterpiece of Fantasy and Reality

One crucial turning point is when he meets Bud’s boss Mr. Johnson, a diner owner who doesn’t know what to do with himself when David inadvertently breaks his routine. When we meet him, he’s literally polishing the varnish off a counter because he’s not sure what to do with himself. Daniels plays this hapless background character to a tee and then grows with him as David, rather than Jennifer, introduces him to a book of famous artwork.

David’s fellow high schoolers are similarly beguiled by books, whose prop blank pages are filled with text when David recalls them. The library suddenly has famously controversial books in stock, including The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, The Catcher in the Rye, and Lady Chatterley’s Lover.

Throughout the film, these awakenings have other unexpected consequences for the town. Most notably, Mrs. Parker does a different kind of self-exploration in the bath one night and enjoys herself so much that a tree catches fire outside. The gag that the local firemen’s sole remit prior to this event was rescuing cats from trees pays off mightily in this scene, but that’s not the only way in which new ideas initially seem to raise the characters beyond their ability to function. Until they burst into color, that is.

In a genius bit of storytelling, David and Jennifer don’t turn back to their normal selves so quickly, and after wondering aloud why that’s the case, each of them discovers in their own way what it takes for them to become enlightened too. Whether they’re canoodling at Lover’s Lane or learning about art and love, these two-dimensional characters shift into color in the wake of a massive cultural upheaval.

Make America Pleasant Again

For the men of Pleasantville, the true terror of the change is epitomised by Macy’s Mr. Parker wandering around his dark and empty home, plaintively asking for his dinner as the town’s first ever thunderstorm rages outside. He’s yet to figure out that his wife is embarking on an affair with Mr. Johnson, whose discovery of art has enabled him to express more romantic feelings. But Mr. Parker sure like to know where his dinner has got to.

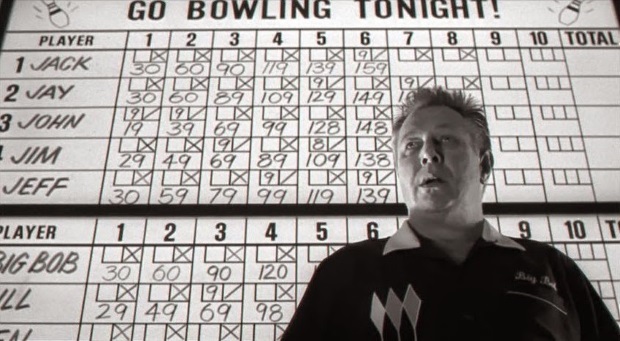

Spearheading the charge to make their town pleasant again is the town’s mayor, Big Bob. Brilliantly played by character actor J.T. Walsh (in his final performance), Bob is determined that the town should be put back in order. Framed in front of a bowling alley scoreboard like George C. Scott in front of the American flag in Patton, he devises a town charter designed to quell the recent outburst of monochrome on technicolor crime, but actually suppresses the newfound freedoms of the latter.

The Patton shot is one of two blatant homages by Ross. The other more famous one is in the climactic courtroom scene, as David and Mr. Johnson are put on trial for creating a colorful mural in the town square. With colored people in the upper gallery and “pleasant” people down below, the film is undeniably harkening back to the 1962 film version of To Kill a Mockingbird, which uses the exact same shot to illustrate segregation.

Ross’ film definitely favors David’s development as a character over Jennifer’s, right up to the reductive and nigh inexplicable ending for her character. It’s a shame, but the film decrees that he’s matured enough by this point to be the Atticus Finch figure at the trial. He now sees the potential that he earlier said these people didn’t have. Putting his screen father and the regressive mayor on the stand, he’s able to colorize both of them, not by corrupting them, but by getting them to reveal who they really are.

Nothing is as Simple as Black and White

Pleasantville, the show, is more clearly a satire of baby boomer conservatism than of American television. Even real-life U.S. sitcoms from around the same time like Leave It to Beaver and I Love Lucy weren’t as anodyne as this. Just as Pleasantville never existed, neither did the nostalgic ideal that it represents. Nostalgia ain’t what it used to be and, like Big Bob’s town rules, most drives to wallow in an imaginary memory of “when things were simpler” usually entail erasing progress that is in some way more convenient to the drivers. Ross’ film states this baldly, but sincerely, in a film that’s as funny and witty as it is visually impressive.

Both of the lead characters mature on their wacky misadventure but ultimately go off in different directions. It’s unclear even within the film’s rules how Jennifer can stay in this world, with the irate repairman swearing that he’ll put everything in the show back how it was. Logical issues aside, it’s significant that when she gets on the bus to college, it’s headed for a place called Springfield.

There are 11 different places called Pleasantville in the United States, but the similarly generic Springfield is also the locale of The Simpsons, which was at the peak of its subversive power when the film was made. As if to underline the fact that it’s a story about nostalgia and the media, Jennifer’s bright future at a… er, fictional college, is once again aligned with the development of TV.

Meanwhile, David returns to reality, turns off the telly, and comforts his mother (Jane Kaczmarek) as she gets upset over her weekend plans, and quite possibly her entire life, being ruined. Startled though she is by his sudden emotional maturity, she has a real conversation with her son at the kitchen table. Presumably right before they have an awkward conversation about his sister’s disappearance.

Touching on issues of fandom, nostalgia, and identity, Pleasantville‘s reach occasionally exceeds its grasp. At times, it feels like a whitewash itself, as a Hollywood re-staging of its central issues. Still, it musters through more critical viewings on sheer imagination. While it’s no ringing endorsement of Turner’s crayons, Ross draws a fascinating line between social and technological progress. As a big screen treatment of decidedly small screen nostalgia, it’s one of the most cinematically inventive films of its era.