Paul Verhoeven’s Hollow Man Predicted the Internet Manosphere

Twenty-five years later, Paul Verhoeven's Hollow Man feels all the more frightening with its vision of a menace hiding behind literal invisibility.

Ask most Paul Verhoeven fans, and they’ll tell you that the Dutch provocateur’s Hollywood career came to a disappointing end. After a 15-year stretch that included classics such as RoboCop, Total Recall, and Basic Instinct, Verhoeven finished out his American movie run with 2000’s Hollow Man, a remake of The Invisible Man that featured incredible effects but also a nastiness that seemed forced and rote, even by Verhoeven’s standards.

Case in point: we’re introduced to our protagonist Sebastian Caine (Kevin Bacon) working late at night in his apartment. His concentration breaks when he looks out his window to spy on a neighbor across the street (Rhona Mitra), undressing as she gets home from work. Caine stares intently as she removes most of her clothing and curses to himself when she finally closes the blinds.

Traditionally in the 1897 novel and in the 1933 Universal horror movie, The Invisible Man protagonist Griffin is either shown or implied to be a relatively good man before he becomes invisible. And to be sure, Caine gets a lot worse once he realizes he can get away with it. But by foregrounding that Caine is an embittered creep from the beginning, Verhoeven in retrospect ensured that Hollow Man was ahead of its time. It’s a portrait of the kind of toxic masculinity that is now a hallmark of modern cyberspace.

Fully Evil Man

Midway through Hollow Man, junior scientist Carter Abbey (Greg Grunberg) attempts to bond with Caine by way of humor. While Caine initially downplays his questions about what it’s like to be invisible, Carter can’t help but go on: “If it was me, I’d be fucking with people, whispering in their ears and shit,” Carter snarks. “I’d be hanging out in Victoria’s Secret. I’d be the fucking king!”

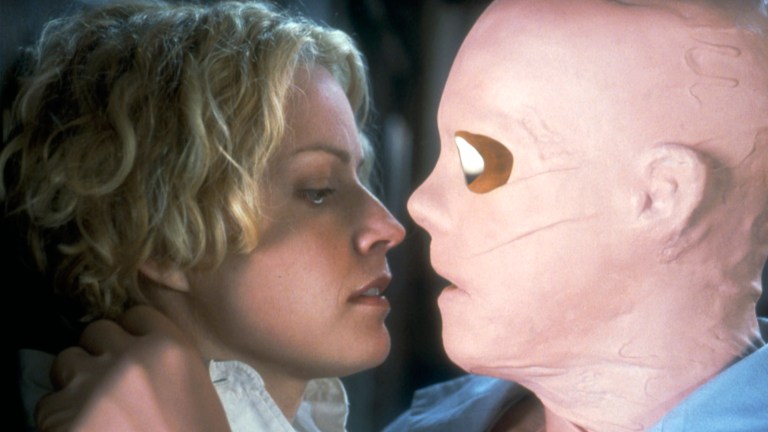

Even under the loose prosthetic skin that Caine at this point wears while invisible—a visual effect that remains impressive even today—we can tell that he’s smirking. Little does Carter know that Caine’s already done so much, including sexually assaulting his neighbor and spying on his fellow researcher Linda McKay (Elisabeth Shue), an ex-girlfriend now dating their colleague Matt Kensington (Josh Brolin).

To Hollow Man‘s original audiences in 2000, Carter’s attempted bromancing was just another example of Verhoeven’s cynical worldview. After all, the filmmaker had already given viewers a pro-fascist satire in Starship Troopers and a dark inversion of the American Dream with Showgirls. He excels at provoking audiences, and by 2000 Hollow Man‘s offenses felt empty and obvious. Yet today the specific nature of Caine’s crimes feel well-observed and all too accurate. Take one of the first things Caine does when invisible: he immediately sneaks out into the main observation lab where his colleague Sarah Kennedy (Kim Dickens) is sleeping. After confirming that she’s in a deep sleep, Caine unbuttons Kennedy’s blouse and begins fondling her.

Given how much the screenplay, written by Andrew W. Marlowe (who shares a “Story By” credit with Gary Scott Thompson), foregrounds the clashes between Caine and Kennedy, it’s clear that this is more than sexual leering on his part. He assaults her because she dared to challenge him, because he wants to exert his will over someone who tried to reject it. Most movies would keep such a blatantly disgusting act until later in the movie, so that we see tragedy in Caine’s downfall. But not Hollow Man. Verhoeven doesn’t see anything admirable in the character—or in anyone else onscreen.

A Visible Problem

When Caine first turns himself invisible, his colleagues gather around to celebrate. Although he can’t be seen, Caine certainly can be heard, as demonstrated by his constant boasting. “I see that the procedure hasn’t changed your personality,” snipes fellow researcher Janice (Mary Randle), delivering the line not so much with disgust but with grudging admiration. Janice’s feelings are hardly an anomaly. Even if Kennedy and Kensington clash with Caine, they always respect him. That’s even more true of Shue’s McKay, as the movie often finds ber grinning at Caine, revealing lingering feelings.

Moreover we believe that they would admire Caine precisely because Kevin Bacon’s so charismatic. Verhoeven takes full advantage of Bacon’s considerable charm, giving him plenty of space to smile and celebrate at his own achievements, and even to suggest that he’s harder on himself than he is on anyone else. But because this is a Verhoeven movie, it’s clear that Hollow Man never shares the character’s love of Caine. People around him love Caine for his hard work, his technological brilliance, and his boldness. But the movie, appropriately enough, sees right through him for the despicable person he is.

That ability to see the horrible person within boasting and success makes Hollow Man imperative today in a way it wasn’t a quarter of a century ago. Today we’re inundated with men whose boasts and success—whether it be the popularity of their podcast, the fact that they’ve become president, or simply their physical attributes—are met with uncritical adoration. These influencers and grifters point to that success to gain followers, who want to learn how to be just like them.

Such behavior certainly happens in all walks of life. But its most obvious and most destructive in 2025 via the form of the manosphere, the part of the internet where people like Andrew Tate and Jordan Peterson assert that their natural genius and power is being threatened by those who don’t properly acknowledge it, namely women. These men are, of course, noxious and pathetic in their boasts, “hollow men” in the sense of the T. S. Eliot poem that inspired the Verhoeven movie’s title. And yet, they gain more and more influence every day.

Showing Toxicity

“You know what, Matt,” Caine sneers to his rival Kensington. “It’s amazing what you can do when you don’t have to look at yourself in the mirror anymore.” That line most directly captures the themes of the H.G. Wells novel and the Universal Pictures film directed by James Whale; an idea that has its roots in the story of the Ring of Gyges from Plato’s Republic. In The Republic, the story of a man with a ring that allows himself to turn invisible (sound familiar?) illustrates the point that it’s only society and laws that allow people to be good. Without that society in place, people will revert to their worst instincts.

It’s no surprise that the misanthropic Verhoeven would agree with that thesis. As upsetting as that idea is, the modern truth is so much worse. Today’s terrible men are completely visible, constantly invading our screens with TikTok videos, social media posts, and press conferences, constantly being platformed to spread their ideas. And those who don’t feel quite as emboldened as those opinion leaders, hide behind a different type of invisibility, with all the comfort that social media anonymity and bot-farming can provide.

Yet the fact that so many of these men are so visible makes Hollow Man all the more urgent. Unpleasant as it is, Verhoeven’s film uncovers the emptiness within these boasts, a reminder that all the talk of success and excellence is little more than an excuse to bully. Hollow Man shows the manosphere for what it is, stripping away the invisibility of social media influence to make the pernicious pretensions plain for all to see.