Paddy Considine interview: Journeyman, directing, Shooting Stars, Statham

Paddy Considine chats to us about directing, writing, Journeyman, his abandoned ghost story, and a majestic appearance on Shooting Stars...

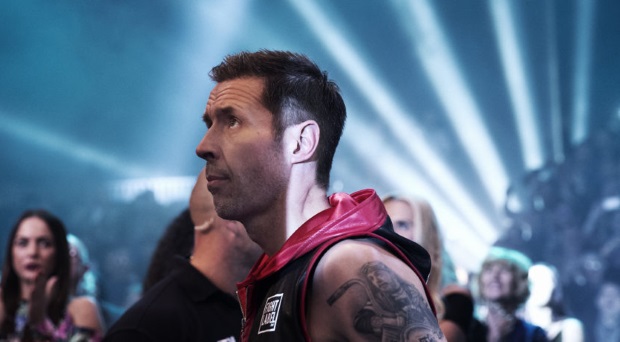

For his second film as director, Paddy Considine has brought to the screen Journeyman, in which he takes a lead role as a boxer whose life takes an unexpected turn.

There are very mild spoilers in this interview, although nothing not given away in the promotion for the movie. In it, we chat about writing, directing, and the day he appeared on an episode of Shooting Stars…

After you made your directorial debut with Tyrannosaur, you said back then that you were working on a boxing film. But that it was an adaptation of the book Years Of The Locust that you were working on. Did these projects intersect, and did it come down to an either/or?

I started writing Journeyman when I was in Glasgow making my first short film Dog Altogether. I started piecing together the beginnings of it then, and made my first submission in 2009 to develop it as a script.

What happened was that when I made Dog Altogether, when you’re a writer you always have three or four things. And after that one, because I left the short film quite open ended, I was being asked by people what happened to the characters next? I sat down and addressed that, and wrote Tyrannosaur.

After I made that, I got it in my head I wanted to step outside my comfort zone and do something else. To go into deeper waters and try to do a bigger project as it were. Maybe I was running before I could walk.

What happened next?

It took a few years. We optioned the book The Years Of The Locust, and it was a film – and still is a project I want to make, and have the publishing rights on it – that I spent a few years toing and froing to America. Meeting with various actors, being told that the script is amazing and we need to get this made.

But nothing was happening. It required a lot of money to make it. We’d spent a lot of our money going over to America meeting people from the story, because it’s a true story. Securing life rights, doing all the things you have to.

On my last trip back to LA, I was there on my own, I took a couple of meetings, and just thought this isn’t going to happen. I’m starting to fall into playing that game. I want the right people for the right roles. It’s not good enough for me to just get a name. We wasted a lot of time and money, and I came back disillusioned. I thought ‘I’m wasting time here when I could just get a film made at home’.

Which is when Journeyman came back to life?

I looked over some of my older ideas. I happened to be walking with a good friend of mine, who’s also a writer, and I told him about Los Angeles and the money we’d wasted. And he said what about that film you had years ago? The one about the boxer who gets the brain injury? It was one of those serendipitous things. It was just that, and I thought ‘what are you doing?’

I went back, picked the project up, and fell into it. When you write as well, you have a few things ticking over and you think you’re going to go in one direction. I’d written a ghost story after Tyrannosaur. I was going to develop that, but then it didn’t feel right, something felt phoney.

It’s a strange thing when you’ve got all these ideas. They almost tell you when they’re ready to be born. It took years to come back to Journeyman. We tried to get films off the ground, but of course I’m acting and doing other things. And so really that’s how it came about, and how it’s taken so long.

I pride myself on asking very dim questions, and so indulge me. How do you write? Because I don’t see you as someone with a mountain of Syd Field screenplay books, for instance?

No! I don’t subscribe to any of that stuff! I’m not a massive fan of reading books that tell you how to write.I think conversations with other writers are interesting. I think writers sharing that idea about creativity and how they go about their work is fascinating. But I think once somebody starts to tell you how to sell a script or shape it, I think you’re in trouble. I think you lose a bit of yourself and a bit of your originality.

The truth is for me is that it’ll tell me when it wants to be written, and I’ll put aside a week or so to write a first draft. I’ll let it take me wherever it wants to take me. For that period of time it consumes me in a writing capacity. And then I know when it’s left me, and I walk away. I don’t labour it. I then come back and sit down again. It works for me. For other people, it works that they keep digging and digging. But because I direct my work as well, I’m reshaping and rewriting on set too.

But to be honest with you, the way that I do it is to surrender to it. I don’t try to be clever, or be smart. I don’t intellectualise what I do or question it. I just do it.

The authenticity in your writing seems key to me.

Yeah. There’s a lot of research. That’s really the main part of it. The biggest part of it all is how it marinades in your head. Then it builds and builds until it’s ready to come out. But there’s a lot of research.

Obviously with Journeyman, because there was brain injury in it, I spent a lot of time researching that, and meeting with Peter McCabe, who is from Headway, the brain injury charity. Paul Brockes, who’s an author on brain injury. Meeting with the right people. Visiting hospitals, units and facilities. And eventually you get to the bit where you’re ready to tell your story. That’s the exciting bit, when the inspiration hits. You’re then ready to begin.

I’ve read a few interviews you’ve done on this film. It seems on this one you’ve talked to boxers when researching this film. But were you talking to the people who live around them, and those affected by what they do?

I didn’t actually speak to boxers about this.

Ah, that’s interesting. I’ve got the wrong end of the stick there.

I made a very conscious decision not to meet with any fighters who had experienced brain injury. I’ll tell you why. You go in any boxing gym in the country now, and everybody has a story. Everybody has the potential to have a film made about them. And I get it in gyms. When people asked me what I was doing, I explained I was making a film called Journeyman, and they’d say ‘oh you can make a film about me and my life’. And so I was very much aware of that, and with the subject matter, I wanted it to be a complete work of fiction.

My research, then, was meeting the families of people who had suffered brain injuries. I wanted with Journeyman for it to be far more universal. I had case studies I worked with in Sheffield that were a fantastic resource, and helped the project.

But that’s the thing about the authenticity, I think. When I was playing Matty in the film, there are real boxing people in there. The people asking questions in the press conference sequence are real boxing journalists. The people helping Matty with his rehabilitation are real OTs and nurses. They came in and treated me like I was a rehab patient, so I wasn’t having to get actors to pretend to be nurses and promoters and stuff.

As a director, the most important thing is you have to create the world, the environment for everybody to step into. So that they can be involved in that story. All I say to any actor who comes and works with me is that you have to surrender to this piece. You are not greater than this piece. It’s not about vanity. You have to step in and let this process unfold with you. Not to try and control it. Just surrender to the process, and it will find its own rhythm. The piece will start to speak to you.

Some people have difficult doing that. Most don’t. Olivia Colman didn’t, Peter Mullan didn’t, Eddie Marsan, Jodie Whittaker, Paul, everybody. But there’s the odd one who hangs on a bit too much, and doesn’t surrender to it. But you have to. The piece will tell you what it wants to be. It’s like a beast, it’ll tell you. Anything it doesn’t want it’ll shake off its back, and you can’t be precious about it. You don’t own it, it’s not yours. You’ve just been given the gift of telling the story, and now you have to honour it.

How brutal is the edit, then? There are single lines in the film that in any other context could feel ordinary. A line that I’ll present out of context so as not to spoil the film for those reading, where someone says “thank you for being my friend”. It’s spine-tingling in the film, but it struck me you’ve afforded it the space to make it work. How, then, does the edit shape up? You’ve talked about writing and directing. But how do you find the edit?

To me, cinema is about moments. I used to talk to Pavel Pavlovsky a lot about this, who I worked with early on. He was a great sort of mentor to me, because he told me it was about creating moments. I understood exactly what he meant, that language. You have to honour the moment. Some filmmakers miss the moment.

On the writing, what I realised when I wrote Journeyman was that I couldn’t intellectualise these people. I couldn’t put rhetoric in their mouths that they wouldn’t speak. I sometimes looked at my script. It’s not a great script where the writing jumps off the page. It was more about the circumstances. What it did have was the sentiment, the message of love in it. That’s what people were reacting to. People would read it and cry.

I knew it wasn’t an incredible screenplay, in terms of its writing. But I knew that the story was incredible. That’s what I believed in. I had to honour it, and these characters.

With the edit of Tyrannosaur, I’m brutal anyway. If I’m cutting the scene with my editor Pia Di Ciaula – if she’s put something together and I look at it and say that’s amazing, I don’t want it touched ever again.

We had a scene in that movie that was amazing. I came to look at it days later and said that scene isn’t working anymore. She said I found this extra bit, and I added that. And I said no: this is done. It’s done. If you find the gold, I’m not going to keep digging.

With Journeyman, it was different. It was a longer edit, and more difficult edit.

Why was that?

I acted in it. And oddly, I couldn’t separate myself from the experience of making it. I was so inside it that when I came to edit the film, for months I couldn’t be objective about it. It was weird. I was looking at the footage and thinking ‘it’s rubbish. I’ve made a pile of shit. None of it works. I was like, we got gold, I know we did. I was there. Where’s it all gone’.

I realised that my head was still in that film. I was still in that house. I wasn’t separate enough to handle the edit. Lesson learned: next time I do that, I’m straight on a plane on holiday for a couple of weeks! [Laughs]The story is the god. I can try and be as fanciful as I want, but my job is to just tell a story.

One of the criticisms of Journeyman is its simplicity, and I think that’s its gift. That it dares to be so simple, and resolve itself. I think a lot of filmmakers now are too scared to end a film, and resolve it in a satisfying way. That’s interesting.

What’s wrong with that? What’s wrong with ending a film? What’s wrong with rounding it up, telling the story, and leaving it in a good place? But it’s not cool to do that.

I have no idea what cool is, you’re safe with me.

Ha!

One thing we try and do with our site is use the audience we have to talk to people who are struggling, who feel life has left them by. I’m conscious that there are talented people who have sparks in them who were discovered at school maybe, or haven’t met a person who tells them they’re really good at something.

If I’ve got this right, a lecturer called Colin Higgins turned things for you?

A tiny bit. When I was at school, I was in danger of throwing everything away. I was pretty unruly in my mid-teens, always on report.

What changed?

I discovered Stephen King. I always loved cinema. I discovered the books of Stephen King and over a summer started reading his work. In my head I started going ‘I want to be a writer, I want to be like him’.

I went back to school the following summer and was given an English teacher called Miss Laws. I’d been terrible to her before. I was in danger of throwing my life away. As a kind of apology to her, I started writing stories, and writing them and giving them to her. She loved them, but for a while I was just writing them to prove I wasn’t a waste of time.

Then I started to take an interest in performing arts. I was in the lower sets, and it was the kids in the top sets who did the productions. We called them the squares. But I did a production called Grease, and I had a teacher called Margaret Balderton, who was instrumental in turning things around for me. She enrolled me then on a performing arts thing at a local college, that I did for a couple of summers. It was great because then I started to mix with other kids. I wasn’t just hanging around on a corner with a gang smoking, drinking cans of lager. I discovered a whole new bunch of kids from different backgrounds. That was a great thing.

But listen, I’m lucky: I’ve had many angels who have helped me. Colin Higgins was one of them. He put me on a film course. I wasn’t even on a course at college, but used to turn up. That’s true.

I had this potential, but no direction. But I think people felt in me I had that potential. I was lucky that at certain times in my life I met people who put me on the right path. If it wasn’t for them, I don’t know what I would have done.

But also in myself, I had this drive to get out.

What would you say to people, then?

I’d say this: if you have a story, tell it. If you have hopes and dreams of doing anything in your life, you can do it. I came from a family where none of my parents worked. We had next to nothing. I was raised on benefits. Nothing is an excuse.

If you want to do it, do it. Walk the extra mile. Sometimes if I missed the bus, I’d walk four miles to college. If you want to do it, don’t let anything stop you. Be driven by the art. Don’t let anybody tell you you can’t do something with your life. I was at a disadvantage, I just kept fighting.

Two final things. I have to ask you what your favourite Jason Statham movie is, given that you appear in one of his finest films?

I’ve only ever seen Lock, Stock and Snatch!

You’ve not seen Blitz?!

No, I don’t really watch things I’ve been in!

I’ll send you a DVD.

Lock, Stock – I thought Jason was great in that. His energy was fantastic. He was doing that thing he did, that fascinating life he had selling goods off the back of a truck. I remember seeing that scene and thinking who is this guy, where has he come from? It was interesting working with him.

Again, I might have misread this, but I recall you saying in an interview that people were looking down on him a little during the making of Blitz, and that you weren’t?

I don’t know if people were looking down on him. I just take people as I find them, and Jason is someone who is a phenomena in his own right. He’s a very successful guy, and people love what he does.

One last question. You were in one of the finest television moments of 2009.

What was that?!

You ended up throwing shoes at Andrew Lloyd Webber’s face on Shooting Stars!

Oh my god! [a transcript doesn’t get across the glee in Paddy Considine’s voice at this moment] Yeah!

I wish I had a question better than ‘what’s that like’, but what’s that like being on that show?

It was like a dream come true. I adore Vic and Bob. I don’t usually do this, because I get asked to go on panel shows quite a lot and I don’t usually do it. But I personally asked to go on Shooting Stars. They’re heroes of mine.

The whole show… I’m embarrassed to look at it, because I’m just laughing and smiling! I learned very quickly that I’m not supposed to go on there and be funny, because they’re the funny ones! You just sit them and let them roll over you.

But I adored every minute of it. I look like a guy who’d won a competition and that’s what it felt like! I love ‘em to bits, and still do. They’re still the funniest guys to me.

Congratulations on aiming so well at Andrew Lloyd Webber’s face, and thank you very much!

Journeyman is in UK cinemas from March 30th.