Movies With Inseparable Songs

A movie can assimilate a song quite easily, and our brains are trained to keep them married...

This article comes from Den of Geek UK.

“Okay, campers, rise and shine, and don’t forget your booties ’cause it’s cooooold out there today.” “It’s coooold out there every day…”

What comes to mind when you see that picture up there? Bill Murray, time loops and themes of growth or redemption? Maybe, but in all likelihood “I Got You Babe“ by Sonny & Cher kicks off, too. Part of that very song might be automatically playing in your brain right now, as clear as if it was floating along the airwaves and through a speaker next to you, wherever you are. When Harold Ramis’ timeless romantic comedy Groundhog Day was released in 1993, “I Got You Babe“ joined a very select group of songs that are quite difficult to separate from the iconic films they’ve featured in, and this recently got us thinking about the different ways this phenomenon happens, and why.

We don’t mean original scores or songs recorded specifically for certain films, or ones that are covered by musicians especially for the occasion, but rather songs that used to stand apart from a film they’ve ended up on the soundtrack of, and have now become indelibly connected to. You could even refer to them as ‘cursed songs’, but we wouldn’t always go that far.

“You ever listen to K-Billy’s ‘Super Sounds of the Seventies’ weekend? It’s my personal favorite.”

When your writer was mulling this over (and make no mistake, there was some serious mulling) the question was thrown out to a few other Den of Geek writers, to see just how many songs came up, and how frequently they were namechecked. “What song can you no longer remove from a classic film sequence?”

Far and away the winner – that is, the one that came up first, time and again – was “Stuck In The Middle With You,” the Stealers Wheel track that plays over Mr. Blonde’s (Michael Madsen at his most Michael Madsen) frenzied cop-torturing scene in Quentin Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs. It’s unlikely that anyone involved in making the legendary crime thriller that kickstarted Tarantino’s Hollywood career imagined that the scene would be unforgettable for so many viewers when they were planning and filming it. In fact, Madsen didn’t listen to the Stealers Wheel song before the first take (one of only three locked down) and the dance he did along to the song was completely improvised, as he admitted at the Tribeca Reservoir Dogs reunion in 2017.

“In the script it said, ‘Mr. Blonde maniacally dances around,’” the actor explained. “And I kept thinking, ‘What the fuck does that mean? Mick Jagger?'”

It ended up being very much not Mick Jagger, and for plenty of people, the Scottish folk rock ditty now reminds them of some wince-worthy extreme torture. For what it’s worth, late Stealers Wheel singer Gerry Rafferty felt entirely more plagued by his hit song “Baker Street“ than he ever did with the track that Tarantino repurposed, as his daughter confirmed to the Daily Record in 2012. She described it as “always a bit of a cross to bear” as he thought it had become the song that defined him, and it even apparently played a part in his descent into alcoholism before his tragic death in 2011.

Songs can arguably be “changed” by being matched to the more macabre moments in cinema. Most movies don’t romanticize their more realistic horrors, but choosing a pop song to accompany a depressing or violent scene can sure as hell make it come across as though that was the filmmaker’s intention, whether they like it or not.

Pairing a notable song with a scene in which a character self-harms nearly always turns a song over to the “inseparable” side, whether it’s during Richie Tenenbaum’s beard-shaving scene in Wes Anderson’s The Royal Tenenbaums (Elliot Smith’s “Needle In The Hay“) or the unnamed girl who has developed an infatuation with James van der Beek’s Sean Bateman (brother of American Psycho Patrick Bateman) in 2002’s The Rules Of Attraction. The aforementioned girl ends her life in the bath in devastating real time to Harry Nilsson’s “Without You,” ensuring you’ll never hear that sad, romantic song the same way ever again.

Meanwhile, in a multi-levelled example, director and convicted paedophile Victor Salva named an entire film after peppy hit Jeepers Creepers (which was itself written for the 1938 flick Going Places) and the song is played and mentioned several times before the movie’s shock ending, where we discover just what happened to Justin Long’s character after he was snatched away by the monstrous Creeper.

For sure, cinema has taught us that these incidents aren’t always akin to the repetitious acceptance of “I Got You Babe” and there are surprisingly few other songs paired with films that have had the impact that “Stuck In The Middle With You” had with Reservoir Dogs (we’re looking forward to hearing about the ones that have connected with you personally in the comments, should you have time for mulling) but the ones that have made the grade do come up a lot with film fans.

Michael J. Fox rocking out to “Johnny B. Goode“ in front of an increasingly perplexed hall of high schoolers at the Enchantment Under The Sea dance in ’80s time travel hit Back To The Future will probably give you better vibes than “Stuck In The Middle With You,” but you might get a contact low from hearing “People Get Up And Drive Your Funky Soul“ by James Brown if your brain has linked it to images of Tobey Maguire cringeworthily dancing through the streets in Spider-Man 3. The weirdness bubbles up to the strains of Roy Orbison’s “In Dreams“ if you’re a steadfast David Lynch fan. Nick Cave’s “Red Right Hand“ might conjure meta scenes of Scream queens trying to escape Ghostface (although Peaky Blinders may have co-opted it by now), while “The Killing Moon” could cause your brain to spit out images of Jake Gyllenhaal frantically cycling home in his pyjamas at the start of Richard Kelly’s 2001 sci-fi masterpiece, Donnie Darko. If we played you “Where Is My Mind?” by The Pixies, would you picture Edward Norton and Helena Bonham Carter watching a skyline full of buildings crumble?

“Yes. You see what I’ve become? See what I must do to survive? Live off another, a mere parasite!”

So how exactly do songs become inseparable from the films they crop up in, and why do our brains struggle to untangle them? We asked neuropsychologist and friend of the site, Dr. Jens Foell, who knows his stuff. He notes that often where these songs are in play, so is a variation of the McGurk effect – an illusion where one sound is paired with a visual of a different sound, leading you to believe there’s a third sound.

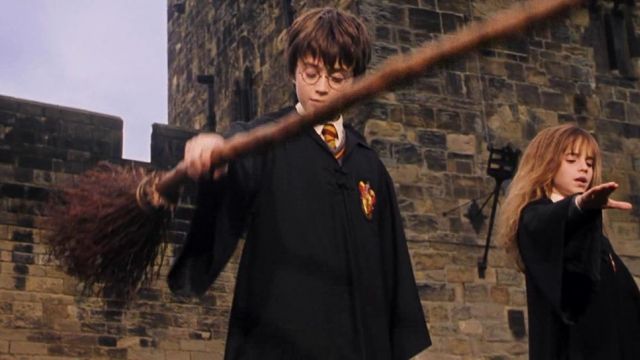

The good Doctor recently treated himself to a re-watch of Harry Potter And The Philosopher’s Stone, which had been dubbed into his native German, and he saw the McGurk effect in full… well, effect.

“When they lift their brooms, the students say ‘up’, but the German voices say ‘auf’. As a result, it sounds like they’re saying ‘aum’,” he explains. “Our vision is ‘stronger’ than our hearing. If you see something that doesn’t fit with what you’re hearing, your brain defaults to taking vision more seriously. This is true for other senses as well — vision usually wins out.”

Reservoir Dogs’ ear-slicing scene provides ample opportunity for its visuals to take control of its song, turning our brain into a comfy home for them both to be consistently linked together in the memory.

“When we hear ‘Stuck In The Middle With You‘ while Mr Blonde is cutting off body parts, we’re not actually really hearing the song like we would on the radio. Instead, we hear a version that is informed by what is happening on the screen. The sounds of the song are being influenced by what we see on screen. Your evaluation of the sounds of ‘Stuck In The Middle With You‘ has now been corrupted by the actions of Michael Madsen.”

In these cases, however, it’s often the emotional reaction we have that seals the deal, he says. “If what our eyes see can influence the very sounds we are perceiving, it stands to reason that this visual information can also alter our emotional perception of the song.”

With Groundhog Day, as you might suspect, it’s not emotions that are running the show, but repetition.

“It’s not necessarily about the perception of the song, but more about what that song stands for. This relates more to basic learning processes: for example, we need to observe a couple of times how a toilet flushes and what it sounds like, until we’re able to hear that sound and think ‘aha, even though I can’t see a toilet bowl around, I’m certain that what I heard was a toilet flush’.”

“You could argue that Groundhog Day hijacks this process: again, and again, it gives us the same auditory cue as something that accompanies Bill Murray waking up, just like the flush sound accompanies the toilet flush. If that happens sufficient times and always happens reliably in that situation, at some point we’re ready to identify that sound just like we can identify the flush. We hear “I Got You Babe“ and we know what it stands for, just like we do it for every other sound we learn in our life.”

Unfortunately, once our brains have put the song and the movie scene together, there are very few ways to separate them, unless another visual component becomes a fresh parasite, a la Peaky Blinders.

“Near, far, wherever you are.”

While this all starts to make filmmakers’ plans to actively elicit a psychological response from the viewer feel a tiny bit insidious, it does usually end up being songs created or covered especially for movies that end up getting right on our tits.

Marti Pellow and the Wet-times-three boys probably didn’t sit around rubbing their hands together in evil glee imagining the aural torture they were about to inflict when they covered The Troggs’ “Love Is All Around for Four Weddings And A Funeral,” but as a nation we collectively suffered through almost a year of movie tie-in song hell back in 1994 waiting for the track to fall off the top of the charts and get the hell out of our heads. Bryan Adams isn’t likely to forget “(Everything I Do) I Do It For You” any sooner than we will, but Celine Dion had been partially forgiven for Titanic’s omnipotent power ballad “My Heart Will Go On“ before she agreed to record the equally addictive “Ashes“ for Deadpool 2 recently.

And who can possibly forget Joe Pesci inexplicably rapping over the end credits of his ’90s slumlord comedy vehicle, The Super? “Gimme the rent! Gimme-gimme-gimme the rent!”

Actually, that one might be just us.

Until next time.

You can read Kirsten and Dr. Jens’ previous article on the psychology of the multiverse right here, and follow them both on Twitter here and here.