Maestro Is the Anti-Biopic That Deserved More Awards Season Love

Maestro is divisive, flawed, and frustrating. It's also a fascinating subversion of the biopics that Oscar voters love, including Oppenheimer.

Maestro has been the source of numerous controversies since the film went into production, and director and star Bradley Cooper has found himself at the center of many of them. From his divisive decision to wear a prosthetic nose to his revelation that he doesn’t allow chairs on set because they cause “energy dips,” Cooper has not always endeared himself to social media during what some see as an increasingly desperate campaign to win an Oscar.

We won’t know Cooper and Maestro’s final Oscar fate until the 96th Academy Awards air on March 10, but Maestro’s award season has been dismal so far. Despite numerous nominations, the passion project has yet to secure the kinds of big award show wins that usually foretell Oscar success. It’s shaping up to be another entry into Cooper’s “award show bridesmaid” career, which is ironically tragic when you consider that many have already labeled Maestro as the year’s most notable piece of Oscar bait.

While the term “Oscar bait” has long been a lazy piece of criticism, it’s been especially frustrating to hear that phrase be used to casually dismiss Maestro. For all of the film’s flaws both on and off-screen, Maestro’s biggest hurdle this award season may just be the ways it subverts and challenges the tropes of one of the most reliable award season contenders: the biopic.

Granted, as a telling of the career and personal life of famed composer and conductor, Leonard Bernstein, Maestro certainly seems to check a lot of award season boxes. It’s a biopic that covers the life of an iconic musical figure who grapples with his sexuality while producing revolutionary works. Hey, if it was good enough for Bohemian Rhapsody.

Yet, one of the most jarring things about Maestro as a biopic is how little it reveals about Leonard Bernstein. The movie not only skips large portions of Bernstein’s life and career (such as his televised Young People’s Concerts series which helped make him a national figure), but it is often quick to gloss over the seemingly monumental moments it does bring up. More importantly, there are times when that lack of information works against the things the movie chooses to focus on. It’s significantly more challenging to follow the story of a man whose life is often consumed by his work, frustrations, and fame when the movie not only refuses to tell us more about those aspects of his life, but sometimes feels hostile toward our desire for such information.

Consider an early scene in which Leonard and his future wife Felicia (Carey Mulligan) are having lunch with a group of friends. One of the assembled suggests that Leonard should consider changing his last name to something less “Jewish” to help his career prospects and public perception. This scene is cut short by Felicia, who suggests that she and Leonard get out of there. They soon do just that in a dreamlike sequence that sees them stand up from the table, walk away, and head straight into a production of one of Bernstein’s hit musicals, On the Town. It’s a bizarre sequence made all the stranger by the fact that the subject of Bernstein’s name and religion in relation to his career is rarely mentioned for the rest of the film. What would usually be a recurring plot point in so many other “you’ll never accomplish (blank)!” biopics is mentioned and then largely brushed aside.

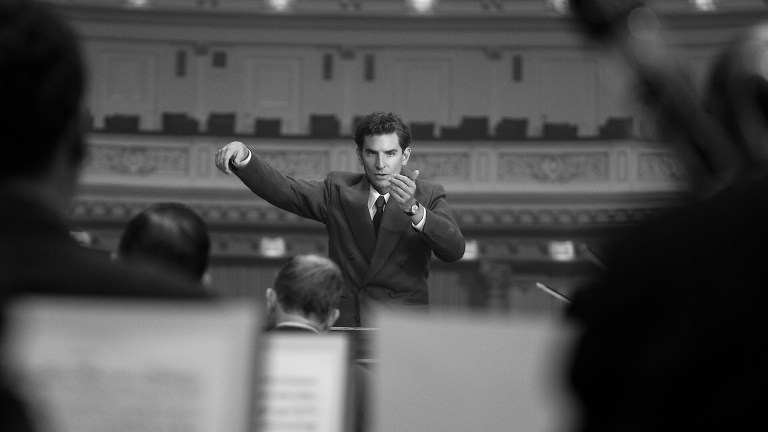

Maestro often addresses similar major moments in the oddest ways. When Felicia catches Leonard kissing another man, she is upset but certainly not surprised. We understand that something like this has happened before but we don’t get to see that moment. When Leonard is interviewed about his career, we can detect some sorrow about his career but we know so very little about what he has done professionally up until that point that it remains forever abstract. For that matter, the movie contains remarkably few sequences of the maestro actually being a maestro (though the few conducting sequences that are in the film are expertly and lovingly shot).

Some of those decisions feel like an extension of the film’s respect for its subject. Much like Christopher Nolan and J. Robert Oppenheimer, you get the sense that Cooper sees Leonard Bernstein as being somewhat unknowable. We try to understand the person this major movie is dedicated to, but those directors seem to appreciate their inability to fully understand their subjects, and the hubris that would be required to pretend they do. And yet, Nolan’s Oppenheimer offers the ample information typically required to draw our own conclusions. By contrast, many walk away from Maestro feeling as if they can’t properly weigh in on someone they’ve come to know so little about.

However, the true power of Maestro may be found in the ways it deliberately withholds that information rather than simply fails to convey it properly. By doing so, the film can more effectively explore what seems to be its greatest message: the abstract absurdity of fame and the idea it can fill that part of us that some refer to as the “god hole.”

Cooper plays Leonard Bernstein as a man who is constantly chasing something that we can’t quite see and which may not actually exist. That’s hardly new ground for a biopic to cover, but Maestro covers it in a rather unique way. Unlike a movie like Walk the Line, Maestro doesn’t portray Bernstein’s life as this glorious rise and fall where the low points are suggested to be at least partially responsible for work so brilliant that we come to justify them in our own minds. Even Bernstein’s eventual ‘coming out” moment, such as it is, isn’t portrayed as a gloriously romantic cure-all. He’s still lost in the life he’s made for himself.

Maestro’s relative ambiguity about large chunks of Bernstein’s life is seemingly designed to help put us in his shoes. People love to keep telling him about his greatness and accomplishments, but he often seems as perplexed by those accomplishments as we sometimes are. If you find yourself asking “who is Leonard Bernstein, and what did he do that made him so great?” consider that the movie often suggests Bernstein is eternally asking those same questions and has yet to find the answers.

More than just another story about a “great man,” Maestro confronts the terrifying truth that there are few accomplishments so great that they can truly fill the part of our souls that desires to understand ourselves and our place in the universe. Had the movie given us more scenes of Bernstein being absorbed by accolades as he conducts and composes at a prodigious level, it would have risked diluting the impact of that idea. After all, we can often justify any amount of struggles in the pursuit of those overwhelming moments of undeniable success that are made all the more glorious because they eternally elude the vast majority of us. Maestro not only denies us the relief of such triumphs but asks: “What if they still weren’t enough?”

For his part, Cooper does an admirable job of playing Bernstein as this man trying to fill an internal black hole and battling the gravitational pull his talent, charisma, and life have on those closest to them. Even still, the movie really does belong to Mulligan’s Felicia, who quickly becomes our vehicle of frustration as she too tries to better understand these complexities that have come to define her own existence to an uncomfortable degree. Though Maestro veers a little too closely to becoming a Lifetime movie by the time it shows Felicia dying of cancer, those final scenes are viscerally effective. It is horrifying to think that she may die without fully understanding what to make of the person closest to her and her relationship with him. Yet it remains easy to sympathize with her given that we too are left with so many questions about what to make of all this.

Admittedly, it feels shallow to argue that a movie that has left so many feeling confused and unsatisfied is designed to invoke those feelings. You could make similar bad-faith arguments in praise of many movies that arguably don’t deserve such a defense. The many negative reactions to Maestro certainly reveal the ways it struggles to satisfyingly convey its biggest themes and ideas or even effectively create more conversations about them.

On a conceptual level though, it’s hard to not at least appreciate Maestro‘s attempts to be more than another biopic. Seventeen years after Walk Hard brilliantly skewered an already tired genre, we’re still having to suffer through biopics that are content to stick to that formula. How many scenes of a musician dryly uttering the words to their eventual hit do we need to endure? In its best moments, Maestro not only defies such tropes but challenges us to confront what we really want from such stories. Do we want to see what makes a famous figure more than just a celebrity, or are we just looking to listen to a greatest hits album played over the retelling of the opening paragraphs of a Wikipedia page?

Maestro is a messy but fascinating exploration of composer Claude Debussy’s insistence that “music is the space between the notes.” It’s a movie that sometimes feels like it consists entirely of scenes that would be left out of other biopics. Yet that structure challenges us to appreciate the power of those moments between the public highlights of a famous life that are as vital to the composition as the major notes themselves. Without effectively utilizing that space between, everything else runs the risk of becoming mere noise.