How Julius Caesar Inspired The Wicker Man

One of the most infamous images in horror cinema owes its power to Gaius Julius Caesar’s political ambitions. But was the colossus real?

For much of Robin Hardy’s cult classic of British cinema, The Wicker Man, you would be excused for not realizing you were watching a horror movie. Granted, this cornerstone of folk horror is bizarre from the word go, and more than a few scenes border on the perverse, yet it functionally is not trying to scare you; the movie prefers to madden and intrigue via the mystery of a missing child on a remote Scottish isle. It also infuriates, because the vanished lass’ only hope is our sour protagonist Sgt. Neil Howie (Edward Woodward), a stick in the mud who clearly slept through the 1960s and will now pay for it on an island led by a man who missed the modern world altogether—Christopher Lee’s delightfully learned pagan, Lord Summerisle.

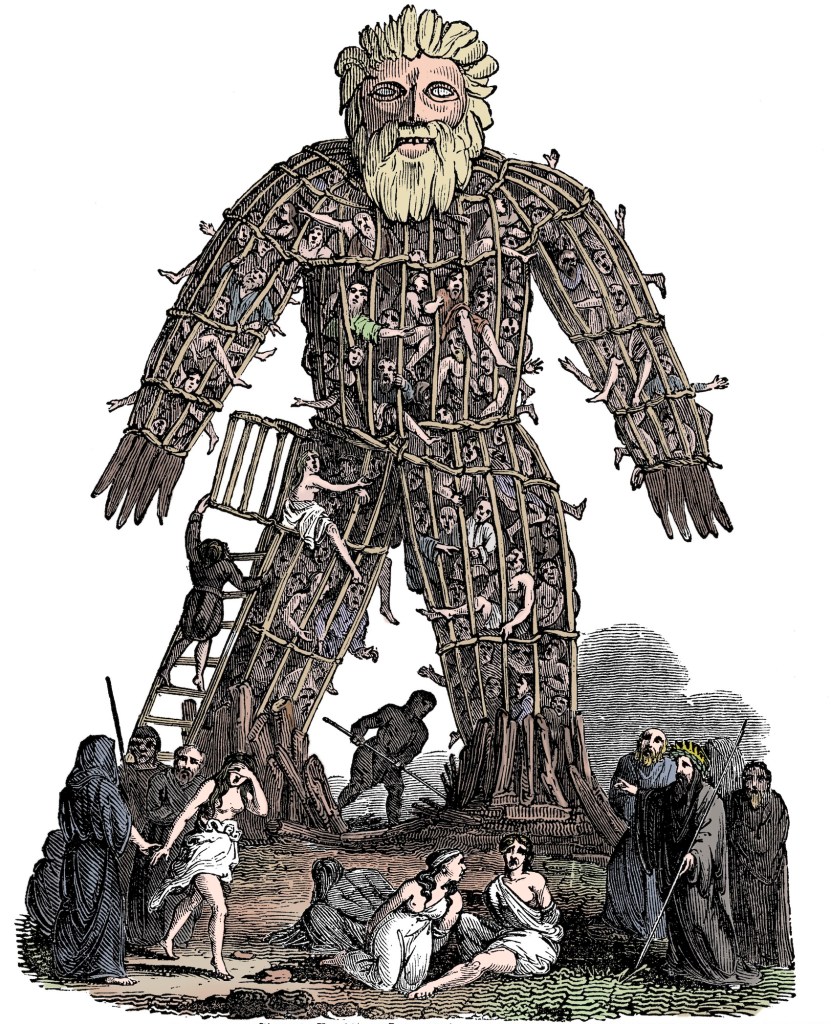

It’s shocking, then, how quickly the film’s dreamy nature changes once Howie and the audience discover what this is all about. In one of the most genuinely terrifying shots in film history, our dear detective finally meets the Wicker Man: an enormous colossus of weaving and ancient pagan superstitions that’s been erected for one purpose. On this pyre, our well-meaning copper will be burned alive.

Before the shot finally revealing the Wicker Man, Summerisle has explained in the abstract that these smiling villagers intend to sacrifice Howie to their Celtic gods, but not until the Wicker Man is onscreen does the full impact of the concept strike us like a lightning bolt. Woodward reportedly requested to not see the Wicker Man structure until it was time to shoot that reaction, so as to catch genuine dread on his face. It works. The moment Howie glimpses his wicker tomb, adorned with all sorts of other livestock and animals to be likewise consigned to the flames, a forgotten primal terror comes rushing back from our collective subconscious.

“Oh God!” Howie screams in utter, witless fear. “Oh Jesus Christ!” Yet his fiery fate is in the form of something older than even Christ—or the modern Christian world Howie represents; it’s an apparition out of an ancient, half-forgotten past. Suddenly, Howie’s moral superiority as a Christian is not taken as the default power dynamic on British territory; he’s stepped into a nightmare where a follower of Christ can still be martyred.

This is the stuff of horror movie mythmaking and still one of the best, if disturbing, finales to any chiller. However, filmmaker Hardy and his source material, David Pinner’s 1967 novel, Ritual, were not making such heinous imagery out of whole cloth. In fact, one of the most famous figures of the ancient world, the Roman general turned dictator, Gaius Julius Caesar, is who we have to thank for the enduring image of the Wicker Man, and the alleged Druidic traditions that kept its flame…

Caesar’s Account of the Wicker Man

Julius Caesar, the man who was pivotal in transitioning Rome from a republic to an empire, yet who did not live to see his name enshrined as a synonym with “emperor,” led a full life even before he crossed the Rubicon and triggered a world-shattering civil war. Prior to that fateful day in 49 B.C.E., Caesar was a transcendent general of legions and a Consul of Rome.

Perhaps he was a little too transcendent for others’ taste (more on that later), which is one of the reasons he published Commentarii de Bello Gallico (Commentaries of the Gallic War) sometime around 50-51 B.C.E. This glorified war journal, which Caesar wrote in the third person, was a selective account of the Roman Consul and his legions’ adventures in the enemy lands of Gaul—-roughly most of modern France, as well as parts of western Germany, Belgium, and a sliver of Switzerland. For fans of the television series Rome, the Commentaries are also where the names of his favorite centurions, Vorenus and Pullo, hail from.

The texts acted as an exotic travelogue of distant lands and even more distant people in need of conquest, which in the case of 1st Century B.C.E. Gaul meant the Celts. Stretching from as far east as the Balkans and as far west as modern day Ireland, the Celts were a dominant religion in these lands and a source of curiosity for ancient Roman and Greek observers, particularly due to their religious leaders, the Druids.

Despite often being mischaracterized in modern pop culture as an entire civilization of folks who practiced “the dark arts,” the Druids were actually a learned and revered class of elders in Celtic society. Druids were typically older men (although “Druidesses” existed) who studied astrology and the natural world, and acted as both religious leaders in Celtic communities as well as proverbial doctors and political advisors. We also know little of their practices because, by and large, the Druids’ entirely secretive customs were committed to memory and never written down. Initiates among the Druids could spend decades learning their rituals and ways, which makes first-hand accounts from those who observed them so valuable.

For his part, Caesar evaluated the Druids’ need for secrecy as thus (via W.A. McDevitte and W.S. Bohn’s 1869 translation):

“They are said there to learn by heart a great number of verses; accordingly some remain in the course of training twenty years. Nor do they regard it lawful to commit these to writing, though in almost all other matters in their public and private transactions they use Greek script. That practice they seem to me to have adopted for two reasons; because they neither desire their doctrines to be divulged among the mass of the people, nor those who learn to devote themselves the less to the efforts of memory [by] relying on writing; since it generally occurs to most men, that, in their dependence on writing, they relax their diligence in learning thoroughly, and their employment of the memory.”

– Julius Caesar

This custom also allowed the truth about the Druids’ rituals and beliefs to vanish from the historical record… although their observers write both respectfully of their philosophical traditions and harrowingly of their religious ones. Indeed, while the Celts, like the Romans, practiced the sacrifice of animals and livestock to their gods, the Druids took those ritualistic practices to a horrifying extreme, according to Caesar. And it is through our Roman general that we have the oldest surviving account of Druids’ affinity for burning men and women alive in the Wicker Man.

Wrote Caesar:

“All the Gauls are extremely devoted to superstitious rituals; and on that account they who are troubled with unusually severe diseases, and they who are engaged in battles and dangers, either sacrifice men as victims or vow that they will sacrifice them and employ the Druids as the performers of those sacrifices; because they think that unless the life of a man be offered for the life of a man, the mind of the immortal gods cannot be rendered propitious, and they have sacrifices of that kind ordained for national purposes. Others have figures of vast size, the limbs of which, formed of osiers [wicker], they fill with living men, which being set on fire, the men perish enveloped in the flames. They consider that the sacrifice of peoples guilty of theft, or in robbery, or any other offense, is more acceptable to the immortal gods; but when a supply of such people is wanting, they have the right to even sacrifice the innocent.”

-Julius Caesar

Hence the potent image where Ritual author David Pinner got his idea to punish poor, poor Sgt. Howie. It gets to something primal, this monstrous effigy in which the rationales of the modern world burn in the wicker flames from the old, including the innocent and damned alike. Two thousand years later, it’s still the stuff of existential dread…. even though some modern historians remain unconvinced it ever existed.

Skepticism Toward Caesar’s Claims

Traditionally, Romans were surprisingly tolerant of other religions from the lands they conquered; the Roman gods are, after all, little more than a repurposing of the ancient Greek pantheon whose devotees the Roman republic subjugated; Rome similarly showed a magnanimous ear to the elders of Palestine or, in Caesar’s own lifetime, to Egypt after he made the next Ptolemaic pharaoh, Cleopatra VII Philopator, his paramour.

So, generally speaking, Rome’s acceptance of other religions from cultures that accepted conquest and/or occupation might give credence to Caesar’s musings on the Druids, a religious sect who would become more persecuted by the Romans than perhaps any other in the empire. Why exaggerate and vilify with descriptions of human sacrifice, an obscenity too great for even Rome, unless it were true?

Well, for starters, when Caesar wrote his Commentaries, Gaul had either not quite been conquered or had just recently been fully subjugated. Otherwise, it was a centuries-old enemy with enmity on both sides. More importantly though, Caesar had political reasons to trumpet that conquest. About a decade before Commentaries was published, Caesar had just been newly made Consul of Rome and a member of the First Triumvirate, alongside Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus and Marcus Licinius Crassus. As such, his taking the legions west and into the wilds of Gaul was seen by some as a way to contain the popular general’s ambition as much as an opportunity to greaten the glory that is Rome. At least he’s out of the city.

And yet, reports of Caesar’s successes—from building a bridge across the Rhine to triumphantly landing in Britannia (if not conquering it)—made Caesar a popular man with the Plebeian class, much to his political enemies’ anxiety. Fearing a popular man, aristocratic rivals began whispering ideas about prosecuting Caesar on his return, stripping him of his wealth and Roman citizenship. When those whispers reached all the way across Gaul and to Caesar’s ear, he reportedly knew he needed to leverage his popularity amongst Rome’s working classes against patrician rivals.

So he wrote Commentaries on the Gallic War as an act of political propaganda, the kind designed to appeal to the Tribunes of Plebs and grow his popularity in lieu of his political enemies attempting to use the tools of state against him. Thus to conquer the Roman public’s imagination, he likely wished to dramatize how important Rome’s subjugation of the Gauls were, which may have motivated lingering on or even inventing salacious tales of human sacrifice.

Nevertheless, we do know that even long after Caesar’s political aspirations were extinguished in a red gush across the floor of the Roman Senate, a general disdain of Druids persisted throughout the Roman Empire, which would come to outlaw Druid practices. It was more than a century later when Roman Emperor Tiberius (himself a lecherous hedonist) banned all Druid practices in Gaul, an act historian Pliny the Elder claimed was done primarily to end an abundance of human sacrifices in the region.

Still, many modern historians question whether the emphasis on Druids’ practice of human sacrifice was overstated by the Romans (who themselves were not immune to acts of barbarity in the name of entertainment and law and order), or whether Caesar and his legions ever actually witnessed Druid customs first-hand. Some argue Caesar based his Wicker Man story off of other accounts.

But then… there are other accounts.

Other Wicker Man Accounts

About 50 years before Caesar marched into Gaul, a Greek philosopher and polymath named Posidonius made a similar journey, except he did not come to wage war. Rather Posidonius lived and studied among the Celts and wrote about them years later in a treatise many speculate Caesar adopted for his own insights into Druidic culture and custom.

Sadly, Posidonius’ account about his time amongst the Celts of Gaul has been lost to history. However, several accounts by ancient historians and philosophers who used Posidonius’ text as a resource have survived. Among them are the works by Greek historian Diodorus Siculus and Greek geographer Strabo.

According to Strabo’s Geographica, which pulled from Posidonius’ non-politically motivated text on the Gauls, the Druids would “prepare a colossus of hay and wood, into which they put cattle, beasts of all kinds, and men, and then set fire to it.”

It is thus from Strabo where the notion that Druids would also include livestock alongside the condemned comes from. And while Strabo says nothing about innocents being put into the Wicker Man structure alongside prisoners, his is the source to suggest that Druids would commit this barbarity if the previous year’s crops failed, as seen in The Wicker Man film.

Modern historians will again be quick to note that all of these accounts are still from a Greco-Roman perspective, and even if Posidinous was not a Roman general, he would have viewed Celts and their Druid traditions as barbaric, although he is noted to have also described Druids as having great wisdom in other matters. There is no concrete archeological evidence of a Wicker Man or of Celts actually burning human beings alive…

There is evidence, however, of them burning animals alive as a form of sacrifice. There is also disturbing and remarkably well-preserved evidence of Celts (and therefore Druids) practicing human sacrifice of a different variety via the famed “bog bodies,” which still litter the marshes of Europe from modern day Germany to Ireland. While there has been some debate whether all bog bodies—which is to say remarkably well-preserved remains of humans and animals that were fed (in some cases alive) to bogs—were sacrifices. Some historians have speculated these are actually the remains of highway robberies or the like. But given some of the bogs have returned to us animals who were once alive with their legs tied together when they were submerged, there is good reason to think otherwise.

More recently, Ned Kelly, the keeper of antiquities at the National Museum of Ireland, has asserted the recent discovery of another bog body in Ireland, this one dated to roughly 2,000 years ago (the time of Caesar), confirms that Celts would not only sacrifice prisoners, but their own kings.

“I am quite convinced we are dealing with an Iron Age male, one who was subjected to a ritual killing,” Kelly said to The Irish Examiner in 2017. “There are cuts and marks on the body that indicate that this is somebody who was done to death… However, it is absolutely not torture, but a form of ritual sacrifice.”

Kelly goes on to reassert how ancient Irish kings were held personally responsible, to the point of sacrifice, for the state of their realms.

“The king had great power but also great responsibility to ensure the prosperity of his people,” Kelly said. “Through his marriage on his inauguration to the goddess of the land, he was meant to guarantee her benevolence. He had to ensure the land was productive, so if the weather turned bad or there was plague, cattle disease, or losses in war, he was held personally responsible.” Perhaps doubly so if the crops turned bad?

So the only assertive evidence of the Wicker Man existing comes from foreign accounts, the most famous of which had a vested interest in depicting the Druids as barbarians (although Caesar was also complimentary to this class in matters of natural philosophy and education). However, Celtic culture did clearly practice human sacrifice through other means, and left evidence of burning animals to their gods as well. Some academics have even made intriguing suggestions that silver tetradrachms (coins) used by Celts in the 1st Century B.C.E. in what would be modern Bulgaria today feature figures that bear a striking resemblance to descriptions of the Wicker Man.

Whether that woven monstrosity ever really existed will likely remain an eternal mystery subject to debate. Yet that unknowable quality makes it all the more deliciously repellent. Several millennia later, Caesar’s description of an apocalyptic colossus remains seared into our subconscious.