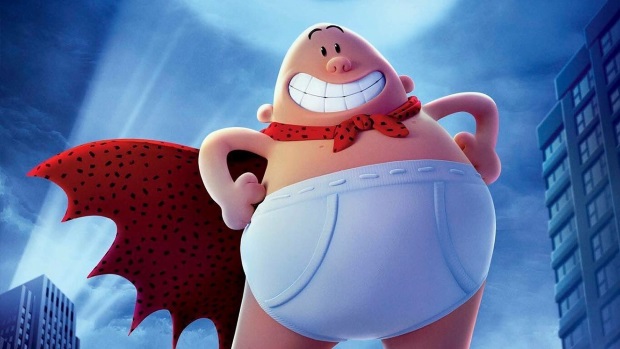

David Soren interview: Captain Underpants six months on

Captain Underpants didn't earn billions, or lots of gongs. But it's one of the best animated films of 2017. We caught up with its director.

Criminally overlooked by most awards bodies, Captain Underpants remains one of the finest animated treats of the past few years. On its release in UK cinemas last summer too, it fell short of the box office totals of the completely shinotverygood The Emoji Movie, and couldn’t land too many gloves on franchise fodder such as Despicable Me 3.

And yet it’s brilliant. It was profitable, too, but not the huge blockbuster success this writer for one thinks it deserved to be.

What, then, does the man who directed it make of the last six months, and of the reception to the film? I contacted David Soren, and we had a chat…

I’m not sure how I’d feel if I were you, and I wanted to start there. I really, really love Captain Underpants, and I think I can probably say this and you can’t: there are animated films released last year, that are getting richer rewards, that are nowhere near as good as yours.

[Laughs] I can’t say that. But I love that you did!

Usually, then, interviews like these are done before a film’s release, but this is slightly different. And I was keen to talk to you about the movie afterwards.

It’s true, this is slightly different.

I think what I’ve come to realise now having done a couple of these movies, and having been in the industry for 20-odd years in various capacities, is that there are certain aspects of the movie you can control and other aspects you can’t. You can make yourself crazy trying to control things that simply aren’t part of the job description.

What I can do is try to make the most of the time I have on a movie while it’s in my hands, and with the crew that I’ve got. Try to use every second and every resource at my disposal to make the best possible film. Then, cross my fingers and hope it turns out to be something we can all be proud of.

I think we did that here.

And now, in hindsight, I do feel like this one will age well. The books have been around for 20 years and they’re still incredibly beloved. I think that the movie represents the books about as well as we could have hoped. Obviously, the box office performance of a movie has an immediate heat to it, an importance, it’s the business side of show business. Then there’s the life of the movie beyond all that.

Have you had experience of that?

Yeah. I was in Seattle promoting Captain Underpants when it was coming out. We went to a school, quite a diverse school in the region to talk about the movie. The entire elementary school was in attendance.

One of the questions I was asked was how long it takes to make an animated movie. I said “It varies. It can be anywhere from two to ten years. For example, I don’t know if any of you have heard of my last movie, Turbo but…” and before I could finish my thought all of the kids in the crowd went nuts. It really, really caught me by surprise. I didn’t realize that movie had the impact that apparently it did, certainly with that group.

What I try to keep some perspective about is that there are the adults watching these movies, and the critical reception, and the box office reception. Then there are the kids that are growing up with these films as part of their DNA. And that’s an incredibly powerful and positive gift to be able to give the world. To have these movies be part of their childhood.

It’s interesting what you say about the adults, though. What happened in the UK is that Captain Underpants opened okay, and then started dropping down the top ten. But then there was a groundswell of critics – and we’re all supposed to be stuffy critics, right? – who started going to bat for the film. Mark Kermode, Edith Bowman, Robbie Collin, people like that.

It was remarkable. I’m so appreciative!

The general critical reception, even in the States, was amazingly positive for a movie with the word “underpants” in the title.

I can’t remember seeing UK critics going to bat so much for a mainstream animated movie in that way before. And I’m curious, in the month or two after the release, how conscious you were that people were spreading the word? Did you get a sense of that, or are you insulated from it?

Well, I’m on Twitter, so I have some sense of it. But there’s only so much of that that’s healthy! Again, though, I think it’s the long game with these movies that is most meaningful. If we’re lucky, and this turns out to be a cult favourite. That’d be phenomenal.

We spoke for the first time when you came to the UK for Turbo. And I remember you saying that how lucky you felt. That you graduated at the top of your class, during what turned out to be a boom time for animation. And thus you landed at DreamWorks and got to pitch and direct your first movie.

What about this time, though? Circumstances were clearly wildly different. DreamWorks Animation was in flux, its distribution deal with Fox was ending, the company was ultimately sold, films were being shut down. Did this one feel a bit more like the imperfect storm?

Yeah, it was a bizarre situation. We were in many ways fortunate that when Comcast bought DreamWorks we were pretty far along on this movie. We were midway through layout, and creatively the movie was going smoothly. We were also a cheap date! I think the new execs were fascinated by the model we were creating [Captain Underpants was animated outside of DreamWorks’ Californian headquarters, and outside of the usual DreamWorks pipeline].

Because there was no real creative or financial reason to shut it down, they let us do our thing and finish the movie. We largely had ourselves to account to, to make the best movie we could.

It was strange. On the one hand, creatively it was easily the most satisfying movie that most of us on the crew had ever been a part of. It was so pure in terms of the creative process. Yet all around us at the studio, things were falling apart. Movies were getting shut down, people were being laid off left and right. It was a very toxic and scary time there. And we were in this little safety bubble working away and having a blast.

It was really bizarre.

It sounds like you have a very odd parallel with Being John Malkovich. That film was being developed by a company called USA when Universal bought them up. And the project landed in the middle of that takeover deal, with Universal then not quite knowing what to make of that film. They saw no creative reason to stop it, and the film could fly off radar because of the moment it luckily landed, just as a massive deal was being done.

Yeah, yeah.

That sounds close to what you went through?

I didn’t know that story, but creatively, for sure we got lucky. Yeah.

We stuck to the plan which had been put in place pre-Comcast. The studio and the leadership on the movie, we all held hands in the endeavour to make this film in a different way. It wasn’t like the plan changed after Jeffrey [Katzenberg, co-founder and animation boss at DreamWorks] left. Mireille Soria was co-president of the studio at the time, and she was also producing the movie. She helped protect us and make sure we had freedom to do what we needed to do within the constraints of our budget and schedule.

It’s a tricky thing making these movies. Especially with animated movies, they take a long time. Things change, executives change. It’s a minor miracle they get made.

You say animated movies take a long time. But you personally came to Captain Underpants late, and it’s no secret that another director was involved in the film beforehand.

But it sounds like what you did was, in two and a half years, retool a film outside of the pre-existing DreamWorks pipeline. And work heavily off instinct due to the contracted timescale, more heavily than you did with Turbo. Would that be a fair summation of how things actually were on this one?

That’s exactly what happened.

When I was approached to come on the film, Mireille Soria described the process that we would be embracing as something like guerrilla filmmaking. It honestly kind of was. There was no precedent for how to do it in this way. There was a lot of figuring things out on the fly. Some of the ways they had initially thought to save money proved wise, others needed to be rethought. Sometimes my spider-sense would go off and I’d have to kick and scream ‘this is not the place to save money. Spend here and then save here.’

We kept rejigging the plan as we went, based on what the movie needed, and to get the best quality on screen.

I have mixed memories of the Spice World movie. But there’s a lovely moment in it when they built up to a massive effects sequence, describe what’s going to happen, and then cut to a toy bus jumping over a bridge. It’s really nicely done.

I can’t help but see an odd, complimentary parallel in your film. There’s a moment where you’re coming up to what would be the trailer moment, and you just cut to drawings.

The ‘flip-o-rama’ moment! Every book has one. It’s a hallmark of the series. We would have betrayed the fans if we didn’t find a way to include it in the movie!

But it was incredibly hard to convince the studio to keep it. For the longest time, everything around it was storyboards. When we did screenings, previews, there was nothing about that flip-o-rama moment that popped. Everything looked the same around it.

The questions kept coming up, the executives asked is this funny, is this going to work? There were a handful of us who truly believed in it and we were like, please, just stay the course with this. Let’s get the film around it finished, but it was really challenging.

That was the hold your nerve moment? Where you wouldn’t know until pretty much the end that it was going to work?

We had faith that it was going to work! We just needed final lighting on the scenes around it to really sell it.

Just a few nerdy bits, then. It is, presumably, a deliberate nod to Bill & Ted that keeps popping up between Harold and George?

You mean their ‘quiet fives’ hand gesture? Nick Stoller [screenwriter] had that in the original drafts, and we never took it out! We didn’t talk about where it came from, though!

On the US disc release, deep in the extras, you talk about cutting a sequence from the film that was set to be a homage to Magnolia, of all films. The moment where the characters all stop what they’re doing and start singing. Magnolia is one of my favourite films…

… it’s right up there for me, too.

How close did the sequence get to making it to the film?

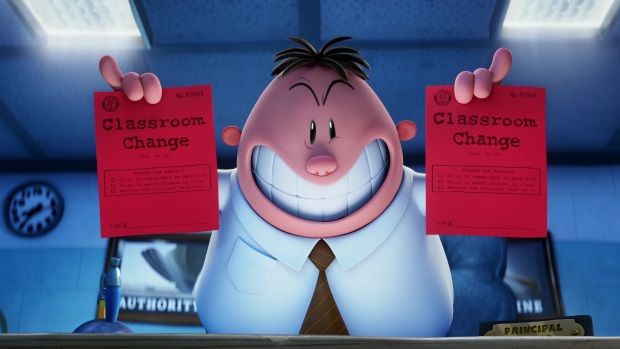

It was actually the hardest section of the movie to crack. The end of act two, low moment. Emotionally, the boys are facing in many ways a lightweight problem – being put in different classes – but we needed to feel the weight of it. To make it feel like the end of the world. And yet not betray the tone of the movie in order to pull that off.

We were trying to be a little bit lighter and a little bit glib about it back in those days. All the main characters from Krupp, to Poopypants, to Melvin, to the gardener outside the school mowing the lawn, had a little refrain. They all sang about how they were feeling unsatisfied by their current situation, and lonely.

Unfortunately, we would have these screenings and it didn’t work. It wasn’t getting in the heads of those two boys. The tone of it just felt off.

We explored all these different other ways. Do we need the boys to be separated into different classes? Do we need to find some other crisis for them in that area? Nothing clicked.

Eventually, we realized we’ve been successful in other aspects of the movie, when we’ve gotten into the boys’ heads and their creativity has led us into their headspace. We tried going into their state of mind.

Asking what it’s like to be taken away from your friend. And how a class down the hall can feel like being on a different planet from each other. We built that out, and made it as cinematic and dramatic and over the top as we could.

Do you at least have the Magnolia material in storyboard form, ready for the Criterion edition of the DVD in ten years’ time?

[Laughs] Yeah, it’s all boarded!

I’ll get onto Criterion now!

You talked about finding the drama in separating two people into different classes. I think that’s a masterclass in relatable stakes. That a lot of movies now are about saving the planet or something along those lines. But then you look at Back To The Future, and how it’s about Marty trying to make sure his parents stay together. At The Goonies, ultimately about a bunch of kids trying to save a house. Captain Underpants: can two friends stay in the same class? It’s beautifully relatable. Was that, though, always the core?

No. When I came on the movie they were struggling with what the stakes were.

There was a subplot going on… I guess it was the main plot… where George and Harold were drifting apart from each other. One was getting in with the popular crowd, the other getting left out. There was a wedge that was growing between them.

The very first thing I said when I took my first meeting on the movie was “This has to go.” The whole success of these books is that George and Harold never once fight.

Their friendship is rock solid, and this is purely about obstacles being put in their way. The damage control they have to do juggling the Captain Underpants and Krupp issue. The crazy villains that come in and out of every book. But their friendship is never in question.

And it’s the glue, you know? It’s the glue that makes these books so beloved. It’s not just a pottyfest. It’s why, I think, the books have stood the test of time – because there’s a super-charming creative friendship at the heart of it all.

Everybody agreed, and fortunately by that point they’d played out that other version enough to know that it wasn’t working. I met [book author] Dav Pilkey about a month after I’d started on the movie. I was pitching him these changes. The visible relief on his face when I told him about the direction we were moving in, it was very validating. He had obviously been uneasy about that other direction, and knew that it wasn’t in character with what he’d created.

After that, he was so empowering and trusting of us. He really was a gem to have as our ally and friend.

Over the course of the movie, we had tons of conversations about theme. In animation, theme is often confused with the moral. That’s not the way I like to think about movies. For me, the theme is like a dinner conversation, where you have different people’s opinions on one general topic. And the more valid each side of the argument is, the more interesting the conflict becomes.

People kept asking, what is the theme of this movie: be careful what you wish for? Too much of a good thing will make you sick? Stuff like that?

None of it really stuck to the wall. We just kept saying this is about friendship, about laughter, and about the importance of those things. But when you’re trying to sell like that, in those general terms, to the studio, it sounds super-flimsy.

Ultimately though, it proved to be much more satisfying to lean into the central relationship of the movie and to have made that relationship between George and Harold as endearing and relatable as possible. And entertaining!

To have leaned into some cliched, generic theme, that wouldn’t have been meaningful for anyone.

With Turbo, they were characters you created, it was a world you created and pitched in the first place. And yet you weren’t hands on with the subsequent TV series.

I read there’s going to be a Captain Underpants show, produced by DreamWorks, that’s going to Netflix. Are you involved with that in any way?

I’m not involved in the TV show. There’s a good team on it and they were going simultaneously while we were making the movie. I had some initial conversations with them, and pointed the way towards some of the artwork we had used to get our characters off the ground. The TV show is 2D (hand drawn), not CG. I’m excited about that and as curious to see the results as you!

The very best of luck with that! David Soren, thank you very much!

Captain Underpants is available now on demand, DVD and Blu-ray in the UK. A 4K Ultra HD release is available in the US.