A Clockwork Orange Ending Is Better Off With Alex Not Being Cured

Malcolm McDowell played an unrepentant sociopath with the charm of a jukebox juvenile delinquent, and he got out of jail free at the end of A Clockwork Orange.

“I was cured all right,” Alex DeLarge (Malcolm McDowell) asserts at the end of Stanley Kubrick’s 1971 cautionary science fiction classic, A Clockwork Orange, and audiences cheered. We left theaters relieved the teenaged thug who’d been beating and attacking his way through the future suburbs of London escaped government brainwashing, conformity, and supplication with his mind, and baser instincts, intact. Good for him. He is free to brutalize and pillage another day. This may be problematic as a working social application in real life, but it is the better cinematic choice.

The film ends on a classically framed shot of Alex (in his mind) happily performing the old in-out in-out with a pleased partner surrounded by an appreciative audience of privileged-class voyeurs. Literally looks like Heaven. It is one of the most memorable and powerful closing scenes in motion picture history. It seems a no-brainer whether it is the perfect conclusion. By viewers’ choice, it is better to retain free will, even if it means uncaging the beast. Or at least letting the beast do what it will, as long as it keeps the zookeepers entertained.

The Cure That Didn’t Stick in the Clockwork Orange Book

A Clockwork Orange explores moral choice, individual responsibility, and free will. All of these are undermined by a brainwashing process in the film called the Ludovico Treatment. Anthony Burgess, who wrote the 1961 novella on which the movie is based, didn’t entirely trust his readers to decide on the conclusion. The first British edition of the book questions whether the story should end with an unreformed Alex.

Burgess published an optional “epilogue” as the twenty-first chapter in the UK edition. At the book’s original close, the malicious malchick is three years older and leading a new gang of young thugs. Alex bumps into his former gang-mate Pete, now married with a steady government job, and imagines himself settling down. The story’s humble narrator begins listening to Mozart instead of Ludwig Van, and decides, at 18, he’s getting a little too old for petty things like crime. Alex is also cured, but it’s not as fun. It would be cinematically anticlimactic.

When publishers W.W. Norton released A Clockwork Orange in the U.S. in 1963, they sliced the final chapter, leaving Alex with the urge to carve “the whole litso of the creeching world with my britva.” The novel is written in a youth slang called Nadsat, which means “teenager” in Russian, the basis of the dialect. Filtered through the street talk, Alex’s violent urges lose visceral effect. Translated, he is saying he wants to carve the face of the screaming world with his razor. Alex remains untamed. The American publishers believed this was a more convincing ending. Kubrick’s film uses less Nadsat, and we get full visual representations of the ultraviolence, which gives Alex’s crimes stronger force than when cushioned by the playful language of the street.

It is important to note that the extra chapter is only an option moving forward. The Ludovico Technique, which brainwashed Alex into submissive acquiescence, is still reversed. The restored prisoner rehabilitation guinea pig gets to enjoy Ludwig van Beethoven once again, and imagine himself slashing his way through life in both versions. The extra chapter is merely an optimistic projection of a character arc, believing Alex will find his place in the world as a person, like other people. Not unlike Travis Bickle, played with the youthful menace of Robert De Niro in Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver, here is another murderous sociopath whose redemption and celebration are shrouded in moral ambiguity.

The film and American printing of the book leave the audience to imagine Alex reverting to his ultraviolent nature. Even with the government’s stamp of approval, it is better than closing on a Pavlovian pup.

When Burgess wrote a film script to be directed by Nicolas Roeg (Performance, The Man Who Fell to Earth) in 1966, he agreed it was the proper ending. He left out the twenty-first chapter. Andy Warhol, who filmed an unauthorized adaptation called Vinyl in 1965, never got past the opening chapter. He didn’t think the story needed anything more than some debauched hijinks in the Korova Milkbar. Never released in theaters, Vinyl shows young toughs inflicting beatings and indulging in near-fetishistic masochism, to fill the voyeuristic needs of a glamorous troupe of Factory players like Gerard Malanga, Edie Sedgwick, and Ondine. The leather-clad youth gang looks like they stepped out of The Wild One (1953), Martha and the Vandellas’ “Nowhere to Run” plays on the jukebox.

Music and brutality go hand in hand in A Clockwork Orange, which is why the Ludovico Technique inadvertently works too well. Wendy Carlos’ score dramatically fuses the brutality with the baroque, but McDowell gives it the beat.

A Juvenile Delinquency Movie About Choice

In a surprise home inspection during the film, Alex’s post-corrective advisor, P.T. Deltoid (Aubrey Morris), warns the underage repeat-offender that the next time he’s caught, he will go to prison, not “corrective school.” These are called “reform schools” in American movies. At its heart, A Clockwork Orange is a glorified juvenile delinquent film, the kind that drove kids to rip apart theater seating after showings of Blackboard Jungle (1955).

Cinema teenagers are traditionally a public menace, and Alex isn’t the first budding sociopath to deal with morality issues on the big screen. In Rebel Without a Cause (1955), Sal Mineo’s Roy Bentley is in the police station because he was caught shooting puppies. Moral ambiguity makes good movies great, and difficult choices make for subversive suspense. Seminal teen crime film Dead End (1937) concludes on a note of uncertainty. When the leader of the E. 54th Place Gang is hauled off to reform school, he is given the choice of having society beat into him or hooking up with a long-timer named Smokey who will teach him how to be a grown-up criminal.

Alex loses the option of corrective school, and the power of choice. It reflected the time in which it was made.

When you think about it, A Clockwork Orange could have been a jukebox musical. After all, what else could a poor boy do except sing in a rock and roll band? The Beatles signed a petition requesting Mick Jagger play the street fighting young man in a film adaptation of A Clockwork Orange, and Burgess originally sold the film rights to the Rolling Stones’ lead singer, who sold them to movie producer Si Litvinoff, who promised to “break ground in language, cinematic style and soundtrack.” The Beatles were going to contribute music.

Before he is captured onscreen, Alex elevates violence to high art, aspiring to be a criminal Beethoven. He gets caught humming “Singin’ in the Rain” in the tub, his most recognizable hit. The final chapter of a Rolling Stones film vehicle may have found the re-maladjusted hoodlums forming a band, possibly called Alex and the Droogs. Not a bad ending, but not a surefire cure either.

Escaping the Brainwashing of the Censors

The British Board of Film Censors ultimately thought the developing project broke too much ground and banned any production of the screenplay, written by Michael Cooper and Terry Southern, who had written dialogue for Doctor Strangelove. Kubrick, who skirted restrictions and blacklists while directing Spartacus (1960), Lolita (1962), and 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), took on the anti-censorship project after the board ruling. He would later instruct Warner Bros. to ban all screenings of A Clockwork Orange in the United Kingdom after tabloid journalists blamed the film for copycat crimes.

By the end of the 1960s, the counterculture still wanted peace, but many had become radicalized over Vietnam, and the films they went to reflected darker tastes. Dennis Hopper’s Easy Rider (1969), and Melvin Van Peebles’ revolutionary Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song (1971) captured a more dangerous independent reality while Ken Russell’s The Devils (1971) and Sam Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs (1971) brought graphic violence to new cinematic levels.

Kubrick thought a film which upped the ante to the point of satire would bring peace. Extreme brutality, an irredeemable protagonist, and an ending without hope seemed like a weapon against rising cinematic and societal violence. Kubrick didn’t realize his lead actor would present a character so magnetic, he would capture the audience’s imagination, which demanded he be set free.

Our Humble Narrator

Although he begins as a violent psychopath, Malcolm McDowell makes it very easy to identify with Alex. The film is told from his perspective. He is the humble narrator. He calls us his “brothers,” “sisters,” and “only friends.” Alex makes us feel like equals. More than sympathetic to the sociopath, the audience lives vicariously as the character indulges dark desires. Alex does what he wants when he wants, and we want him to. We have no reason to think he will change and we urge him on, even as Alex grins while telling the admitting prison guard his crime is murder. He thinks the distinction will earn him points in prison.

“He’s enterprising, aggressive, outgoing, young, bold, vicious,” The Minister of the Interior (Anthony Sharp) concludes before shipping Alex off to be transformed out of all recognition.

Kubrick presents Alex as a product of his environment. P.R. Deltoid is only doing his duty in the book, urging the young criminal to stay out of trouble and conform. The film portrays him as a budding sexual predator, grooming the teenaged menace for something sinister, perhaps like all authority figures. The adult world looks pretty depraved, and Alex’s only real crime is going too far, killing the wealthy cat lady (Miriam Karlin) with a “very important” phallic sculpture. Is that any reason to have his mind ripped from him?

This Is Some New Form of Torture

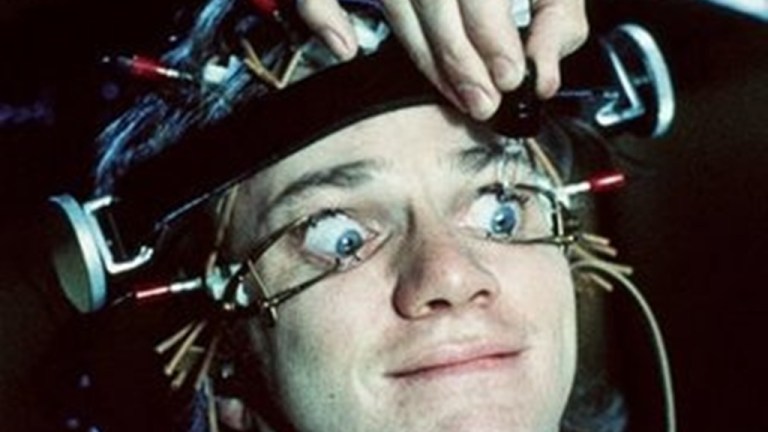

The experimental Ludovico Treatment is horrific. Far more so for the audience than the crimes Alex commits. Combining a physically debilitating drug with behavioral conditioning, including condition-reflex therapy, subliminal torture and neuro-manipulation, Alex’s inner world is destroyed by outside forces. His eyes forced open by “lid-locks,” Alex is forced to watch graphic depictions of bloodshed and sexual violence while the drug he was administered brings the nausea normal people are expected to feel when they see these things. “Violence is a very horrible thing,” Dr. Branom (Madge Ryan) explains to Alex. “That’s what you’re learning now. Your body is learning it.”

The ongoing, hours-long sessions force Alex to experience physical and mental pain at the mere suggestion of sex or violence. Chief therapist Dr. Brodsky (Carl Duering) presents the Ludovico Technique as an advancement of science, a humane method of rehabilitation. Alex is dehumanized, hyper-sensitized, and emasculated by the Ludovico Treatment. When he is put on display for the interior ministry, he is forced to take abuse and lick shoes, emotionally disintegrating at the very sight of nudity.

“The first thing that flashed into my gulliver was that I’d like to have her right down there on the floor with the old in-out, real savage,” Alex admits to the audience. But all the newly programmed youth can do is reach up and hold back the bile growing in his throat.

The Minister of the Interior is sitting in the front row. This is an inspiration to all. He is not concerned with motives or the higher ethics; he is “concerned only with cutting down crime.” Alex was just a convict, number 655321. But the audience sees the larger picture: Alex is a man in his natural state. If he is cured by the Ludovico Treatment, civilization is a neurosis imposed by the society. If Alex goes on to naturally conform, as he does in the book, the brainwashing loses its horror. The audience almost empathizes with the government.

Alex’s good behavior is artificial. He did not undergo a genuine change. He will, however, comply.

Initiative Comes to Thems That Wait

The ministers don’t care what happens to Alex after they pack him off in the suit he came to prison with, and all but his cigarettes and chocolate in the strung together paper satchel he carries. Alex is rebuked by his parents, accosted by his first victim, an elderly homeless man he kicked for singing, and dragged off by Dim (Warren Clarke) and Georgie (James Marcus), now policemen, to be beaten, almost drowned, and left for dead. It follows the trajectory of many ex-convicts. The state has no use for them unless they have a use for them.

Frank Alexander (Patrick Magee) is the first person to see Alex as the mechanical toy he is: the clockwork orange. Wind him up to serve the state, make him jump to oppose it. If only the poor victim wasn’t the specific person who sexually assaulted the subversive writer’s wife and confined him to a wheelchair. Kubrick’s film dispatches Alex’s victims with little regard. The writer is labeled crazy, discarded, and forgotten. Viewers are more offended by the violation of Alex’s individuality. That hits home. Restoring that gives a kind of hope.

When Alex regains his basest impulses, justice feels served. Britain’s Minister of the Interior apologizes for the Ludovico Treatment, blasts the Ninth Symphony, and asks for Alex’s support in the next election. The restored villain gets the elected public servant to serve him food. It looks like Alex is up to his old tricks. Order and uniformity are maintained. Alex is free, but at the mercy of a corrupt system. The state doesn’t care about rehabilitation, only the appearance that everything is under control.

Real Horror Show

Kubrick’s changes to Burgess’ novel are similar to the distinctions he brought to Stephen King’s The Shining, a ghost story directed by a man who doesn’t believe in ghosts. In the book A Clockwork Orange, Alex is a victim of the state, the film makes Alex an accomplice. The government rewards the cruelest members of the society by putting them to work controlling everyone else. In the film it appears Alex looks forward to giving in to his violent tendencies. Who’s going to stop him, the state? They just bought him a surround sound stereo system.

This delivers the film’s final message: The only ones who are free are granted that status through political privilege, which is not based on moral merit. It is the scarier ending because it means you can get away with anything if you have political backing.

The real genius of the film’s ending is it leaves the true horror not only intact, but thriving in the audience’s imagination. Alex gets to have his eggiwegs and eat them too, because of governmental privilege. He’s more useful to the state as a violent thug than a poster boy for mind-crushing totalitarianism. The audience can imagine Alex moving forward as one of the hoodlum cops given free rein to bash in the heads of innocents. He’s cured, alright. It’s funny how the colors of the real world only seem really real when you viddy them on the screen.

A Clockwork Orange can be streamed on Netflix.