25 stylish French films worth watching

Covering 85 years of cinema, Aliya provides her pick of 25 stylish, must-see French movies...

I’m going to kick this off in best New-Wave style by pointing out that we should be praising each great director’s body of work rather than showcasing favourite movies in a list format; after all, France came up with the concept of the auteur filmmaker, stamping their personality on a film, using the camera to portray their version of the world.

Yeah, well, personality is everything. So here’s a highly personal choice, arranged in chronological order, of 25 of the most individualistic French films. They may be long or short, old or new, but they all have one thing in common – they’ve got directorial style. And by that I don’t mean their shoes match their handbags.

The Passion Of Joan Of Arc (1928)

There are no stirring battle scenes, no looking great on horseback or wearing of beautiful armour in this version of the story of Joan of Arc. Carl Theodor Dreyer’s film concentrates entirely on the trial for heresy that sent Joan to the stake. This is about accusations and guilt, and how far faith can be tested.

The faces look so contemporary in this film. The nakedness of expression is moving, and Maria Falconetti is an amazing Joan of Arc, with wide eyes, brimming with despair or blazing with religious conviction. She changes from vulnerability to insanity in a moment. The acting is incredible, and so is the camerawork, panning over the faces of Joan’s accusers, tracking them as they move from room to room, seeking out odd angles so that the viewer never becomes comfortable. Joan suffers so visibly; there is a transparency to her. Whether you are religious or not, the effect is overwhelming.

The Rules Of The Game (1939)

This is a film about society – where you stand in it, how you keep your status, the things you are allowed to do, and the things you keep hidden. The gentry meet at a country house for a hunting expedition. They have affairs, which must not be talked about. The servants have their own problems, but when these erupt into violence the gentry must not see them. It’s below their standing to get involved in such things. And we are aware, as the camera tracks through the great halls and along the polished floors of the chateau, that this aristocracy has had its day; World War Two is upon them, and everything will change.

There’s a great scene in this movie that takes place after dinner, when the guests come together for entertainment. The mechanical piano plays Saint Saens’ Dance Macabre, the keys moving by themselves, and on the stage three ghosts and a skeleton appear, jigging up and down to the music. They leap into the audience and terrorise them, but everyone sits still and laughs. After all, that is what is expected of them. Nobody can break from social convention. And we sit and watch the entertainment too.

Orphée (1950)

Jean Cocteau was best known in France as a poet and novelist, but he also made such beautiful fantasy films. Orphée is a modern retelling of the Orpheus myth. In this version, Orpheus is a poet who has run out of inspiration. When he meets Death in the form of a princess, and strange messages start coming out of his car stereo, he becomes obsessed. He neglects his pregnant wife, Eurydice, and when she is killed he realises his selfishness and sets out into the Underworld to find her and bring her back to life.

This film is so inventive, and strange, and it’s all about the big questions. Is love stronger than death? Can a person love death more than life? What is the nature of happiness? And how is it possible to visit the Underworld using only a pair of rubber gloves and a household mirror? It’s a mixture of fairy tale and absolute seriousness. The Underworld is stunning to look at – a bombed out city, rubble-strewn, bringing us to the realisation that World War Two has only just ended in the world of Orpheus, and Death walks beside him.

Olivia (1951)

Olivia is the tale of a young girl who arrives at a boarding school that is run by two headmistresses who are in a struggling relationship. The girl develops a crush on one of the headmistresses, and unwittingly puts herself between them, leading to jealousy and rage.

It’s a very traditional looking film, with a soapy Hollywood feel that is at odds with the controversial subject matter. Directed by Jacqueline Audry, the only woman at that time to direct commercial French cinema, everything is neat and shiny and the girls at the boarding school are pictures of prettiness. This makes the outbursts of the jealous headmistress ugly and difficult to watch. Olivia has a cult following, I think because it deals with lesbianism in a very direct and non-voyeuristic way. This is not about showing us kissing or heavy-petting, or breaking boundaries. It’s about the normality of having a schoolgirl crush, for whatever gender. Made in 1951, featuring an all-female cast, it’s far from the New Wave, and yet equally as daring in its own way.

Diary Of A Country Priest (1951)

The title makes it sound like a pleasant romp through woodlands, but this film is not at all light-hearted. It’s a slow, claustrophobic meditation on faith; the new priest, sickly and confused, arrives in a small French village and finds the ways of the locals closed to him. He is the ultimate outsider – mistrusted, given strange, conflicting advice. He received anonymous letters and bears slights from the village children. It’s painful to watch his suffering.

Director Robert Bresson gives us the face of actor Claude Laydu to watch through these random events. The camera follows his eyes with a careful framing, showing us his isolation in cold rooms, against the flat landscape. There’s a dispassionate monologue – the internal voice of the priest – that informs us how he feels, what he wants, as his expression gives away nothing. Scorsese uses the same style in Taxi Driver, the film that gives us another tortured soul, this time without the comfort of faith. There could not be a Travis Bickle without this country priest. It’s also easy to imagine it was an influence on Haneke’s The White Ribbon.

The Wages Of Fear (1953)

Just in case you think French film suffers from a glut of navel-gazing and long pauses, Clouzot’s Wages Of Fear is one of the most exciting screen adventures you could watch.

Clouzot understood suspense. He could make you sit bolt upright in your seat, unable to take your eyes from the screen. In this story of four men agreeing to drive a shipment of volatile nitro-glycerine through jungle roads in South America, every jolt of the two trucks could be fatal. Not a shot is wasted. We see the fear behind the machismo, the desperation behind the posturing. We emotionally invest in these men even as we know they might be blown to bits in a moment. It’s a grimy, frightening, gut-wrenching experience – but you wouldn’t want to miss a moment of it.

Night And Fog (1955)

Out of all the films I’ve seen, this one is the most memorable. It’s also the only truly great film that I wish had never been made.

A short documentary, Night And Fog intersperses black and white footage recovered from allied forces with colour shots taken in the remains of Nazi concentration camps on Polish soil. Some of the footage was considered to be so upsetting that the French government made it available only for this film. It’s impossible to look away. Just as you think you can’t watch any more, with perfect timing the camera cuts back to the green meadows that have overgrown the camps, and the voice-over asks you: if we refuse to accept that we did this, how can we be sure this won’t happen again?

Director Alain Resnais made later films that meditate on how time affects us, moves us away from the most tragic events, separates emotion from meaning. Hiroshima Mon Amour and Last Year At Marienbad are both amazing films. Night And Fog is the most powerful film he shot. François Truffaut thought so; he called it ‘the greatest film ever made’. And yet it’s not a film to be watched more than once. Once is enough.

The Red Balloon (1956)

Albert Lamorisse made short films into which he packed an incredible amount of loving detail; for instance, when you watch White Mane (1953), you become a part of the landscape of the Camargue, running with the wild horses. In The Red Balloon you see Paris with fresh eyes. The greys and browns of the city, the shapes of the doorways and rooftops, are a patchwork into which a single circle is woven. The colour is intense.

Throughout the film, Lamorisse’s direction is as playful as the balloon. There are the bangs of backfiring buses, the sharp spires and the points of umbrellas, always reminding the viewer that the balloon, like childhood, is a temporary gift only – no matter what delight it brings to us, it is a bubble that must, eventually, be popped. Except that Lamorisse won’t take The Red Balloon to its inevitable conclusion; he embraces the magic of film and whisks us off in a new direction.

Not only did Lamorisse make beautiful films, but he also co-created the board game Risk. That’s not at all related, but I just had to throw it in here. Cool, huh?

The 400 Blows (1959)

François Truffaut kicks off the French New Wave by making a film that is so personal, so recognisable, that it reminds you of what it was really like to be a child, with none of this red balloon nonsense. Instead we watch 12 year old Antoine (Jean-Pierre Léaud) try to make sense of a school that stifles, and a family that blames. The few experiences of happiness he has come with friends who encourage him to play truant or steal small items; soon he’s on a path that leads to delinquency and ruin.

The key moments of The 400 Blows occur when nothing seems to be happening at all. A boy makes a smudge in his schoolbook and tries to rip out the pages to avoid getting into trouble, or Antoine stokes the fire with coal and then wipes his hands on the curtains. The next punishment is always on the way, even when the children try to do the right thing. There is no freedom, and the cramped apartment and regulated schoolroom are used to great effect, giving us that feeling of claustrophobia that is only relieved in the great last moments of the film.

Eyes Without A Face (1960)

This film is utterly creepy, and incredibly influential in modern cinema worldwide, from Japan’s The Face Of Another to Spain’s Open Your Eyes and The Skin I Live In, with Hollywood’s Face/Off along the way. I also think that the blank staring mask of Michael Myers in John Carpenter’s Halloween owes something of a debt to it.

The director, Georges Franju, understood the importance of the eyes in cinema – the way the gaze is drawn, the way a stare captures our attention and holds it. The eyes of Christiane (Edith Scob), the victim of a disfiguring car crash, shine out from her perfectly white mask with a bruised horror. Her father attempts to graft the faces of other women on to her own. We can’t see her expression, but the eyes tell us what we need to know.

The thing I love most about Eyes Without A Face is the score. It has a joking quality that makes your skin crawl. This was Maurice Jarre’s breakthrough; after this he went on to write the score for Lawrence Of Arabia, and then huge budget productions such as Witness and Fatal Attraction. I don’t think he wrote anything quite as spooky as this again, though.

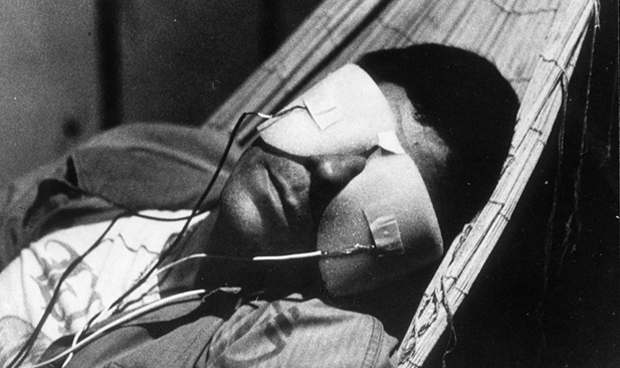

La Jetée (1962)

An absolute original, La Jetée is a short film almost entirely made up of stills. It documents a post-apocalyptic nightmare where humanity survives in tunnels under the surface of the Earth. In an attempt to find hope for mankind, a time machine is invented, and a nameless criminal is chosen to be flung into the past and future. He survives numerous trips, and falls in love with a Parisian woman, who starts to shed light on experiences in his own past.

The film raises so many questions about the nature of love, time, and memory that stay with you long after viewing it. And the one moment of action, where we watch the woman open her eyes in the morning light, waking from sleep, is so wonderful amidst the harsh stills and the neutral voice-over. It’s incredibly moving.

Contempt (1963)

Jean Luc Godard made radical films that test the boundaries of the viewer in all sorts of ways, including their patience. Contempt is the perfect title for this film. It’s as contemptuous of the plot-driven demands of the modern audience as it is of Hollywood. This is the only time Godard made a big-budget film with American money.

Screenwriter Paul Javal (played by Michel Piccoli) is brought in to ‘fix’ the script of Fritz Lang’s film about Homer’s Odyssey. He encourages his wife (Brigitte Bardot) to be friendly to the brash American producer (Jack Palance) who obviously wants to bed her. Everything is about money, and power. Palance is very funny, declaring himself a god and using his secretary as a table. Fritz Lang appears as himself, looking dignified and lost in this age of fast cars and chequebooks.

At the time this film was made Brigitte Bardot was the sex-kitten of the world. The story goes that one of the producers, Joseph E Levine, insisted on a nude scene, and Godard gave it to him. It’s at the very start of the film, and it’s shot through a filter, the camera moving down over her bottom and legs with detachment. If you ever wanted to know if it was possible to make a film that you hated about a subject that you hated, here’s the proof. And it’s still an amazing piece of work.

Belle De Jour (1967)

If Hollywood ever does get around to making 50 Shades of Grey I’ll bet the film will be nowhere near as interesting as Belle De Jour. Catherine Deneuve plays Severine, a woman who can’t stand physical intimacy but fantasises endlessly about sadism, humiliation, and bondage. She refuses the advances of her glamorous, good-looking husband and seeks out a brothel, where she agrees to work until five o’clock every day. The clients are ugly, strange, downright weird – and she accepts them all.

Luis Bunuel made a spectacularly non-judgemental film. There’s no bad guy in this, not even the gangster who becomes obsessed with Severine and attempts to beat her with his belt (a great performance by Pierre Clémenti). She’s not unhappily married – she simply is unable to verbalise what she desires. So the camera speaks for her. It shows us her fantasies and it never feels degrading. Eventually fantasy and reality start to bleed together, and the film ends with an open-ended surrealism that suits it perfectly.

You can see the influence of Hitchcock on Belle De Jour, particularly the use of colour and the attention to the details of hair, handbags, shoes – particularly Marnie, I think, made three years earlier. And maybe, in turn, this film influenced Haneke’s The Piano Teacher, another great meditation on the difference between sexual fantasy and reality.

Le Boucher (1970)

Schoolteacher Helene (Stéphane Audran) meets the local butcher at a small town wedding, and they become friends. He brings her fresh meat, and she gives him a cigarette lighter as a present. But then she discovers the lighter at the scene of a grisly murder…

If you think this sounds like a Hitchcock film, I’d have to agree. The cigarette lighter motif, the car journey in the dark, the use of colour throughout – we know things are building to a horrible realisation for Helene. We’re in the position of knowing more than her, and it makes Le Boucher a really uncomfortable film. It’s the feeling of watching her, examining her as a victim, that infuses the movie with horror even though most of the time things are quiet, even sedate.

Les Valseuses (1974)

Les Valseuses starts with a pure 1970s Benny Hill vibe to it, with cheeky music and deliberately comic angles as two petty criminals in a shopping trolley chase a portly middle-aged lady down the street and poke her bottom. But then we see her terror as they corner her and molest her, and we realise this is not Benny Hill territory at all. This is the darker, nastier side of the sex comedy, and as a viewer you feel strangely ambiguous about it. You should hate it, but you watch it, and you laugh.

Perhaps it’s because Gerard Depardieu and Patrick Dewaere are just so good in it. They are clownish, charismatic, sometimes caring. They’re also sociopathic. The people they help or hinder don’t seem to be quite real to them – they are the stars of their own movie, in their heads, and nothing else matters. In that regard, Les Valseuses is at times the forerunner of films of cruelty, such as Michael Haneke’s Funny Games.

Director Bertrand Blier continues to make films; his latest, The Clink Of Ice, deals with a man with cancer. Then his cancer, in human embodiment, knocks on the door and comes to visit. His work remains as interesting and divisive as ever.

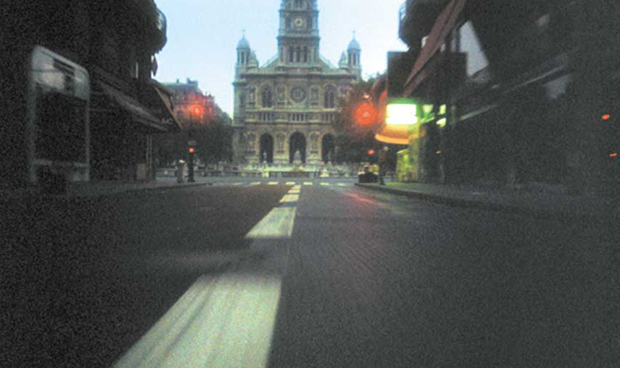

C’était un rendez-vous (1976)

This is a really short film – nine minutes long. It’s a car journey through the streets of Paris, just after dawn, with deserted streets. You see the road unfold before you as you rush past landmarks and wind your way up to Montmartre. And at the end of the journey waits a good reason for breaking the speed limit and ignoring the red lights.

Claude Lelouch, the director, used his own Mercedes (the driver’s identity has never been revealed) and put the sound of a Ferrari engine over the footage. The roads weren’t closed and no permission was obtained to film – for this reason he was arrested shortly after it was released, but released without charge. A mystique has built up around the movie for these reasons, but another really good reason to watch it is that it brings Paris to life in a way that no other film has managed. It’s real.

La Cage Aux Folles (1978)

Movies based on theatrical plays often struggle to transcend the fixed structure of the stage. That static look on screen is a giveaway in such films as Dial M For Murder and Sleuth, which are great films, but have a staged quality to them. The camera often has a fixed point, and the actors walk in and out of shot.

La Cage Aux Folles has to be one of the most successful translations from stage to screen because it’s about living life as if you’re on a stage. Everything is a performance for lovers Renato (Ugo Tognazzi) and Albin (Michel Serrault); one is the owner of a cabaret show and the other is the outrageous star turn. They live in a small apartment and are very happy, but Renato’s son has just got engaged to a daughter of very conservative parents, and so Renato and Albin stage the appearance of being a ‘normal’ family in order to please him. It’s a farce, extremely funny, and even though it is sometimes accused nowadays of dealing in stereotypes of homosexuality, the characters do have a real depth and warmth to them. They aren’t ashamed of who they are – the staginess comes naturally to them. Only when they try to cover it up for the sake of their son do they become unhappy.

It has a powerful message wrapped in a light-hearted comedy, and the message of acceptance endures. In 1996 Mike Nichols directed the American remake with Robin Williams and Nathan Lane as the lovers, which is by no means a bad film. But why watch a pale imitation, when you can go straight to the diamond-studded star of the cabaret?

Jean De Florette (1986)

There’s a Shakespearean quality to this tragedy. Everything is big: the landscape, the performances, the weather, and the arc of the plot. It’s a classic story of good versus evil – Jean (Gerard Depardieu) moves his family to a plot of land he has inherited and struggles to water it because of the greedy machinations of the locals, who want the local wellspring for themselves. Jean is such a good-hearted character that he can’t see a conspiracy. His own open, enthusiastic nature is his fatal flaw.

Provence is the setting for the film, and the beauty of it is as much of a feature as the story, taken from a 1964 novel by Marcel Pagnol. A marked increase in tourism to the area was considered to be as a direct result of the international success of the film.

Of course, I’m not really recommending just Jean De Florette. I’m recommending Manon Des Sources as well, which is not so much the sequel as the completion of the story. But you knew that already, right?

Cyrano De Bergerac (1990)

More Depardieu, this time as France’s most famous lover. Cyrano was a real person about whom untrue stories have sprung up over time, although, to be fair, he does appear to have a pretty big nose in portraits from the 17th century. A lover, a fighter, a poet and a man with panache, Depardieu gives a great performance in Jean Paul Rappeneau’s version, which is huge and bombastic, and totally in keeping with the character of Cyrano.

Unless you speak French, you’re at the mercy of the subtitles when you watch any film on this list (if you don’t opt for the usually terrible dubbing) and yet it’s part of the experience that never gets a mention. This film has the best subtitles of any film I’ve watched. They’re written by the great novelist Anthony Burgess (author of A Clockwork Orange), they’re almost entirely in verse, and they are brilliant.

There are a number of Hollywood versions of Cyrano De Bergerac. I think my favourite is The Truth About Cats And Dogs.

La Femme Nikita (1990)

Nikita is a young woman with no future. Drug-addicted, despairing, she kills others and instead of being sent to jail is inducted into a government training programme – to hone her skills as a killer into a usable weapon for those in charge.

What a stylish movie Nikita is, but with real substance. Director Luc Besson gives us the first female assassin; without Anne Parillaud’s brilliant performance there wouldn’t be a Long Kiss Goodnight, a Dollhouse or a Kill Bill. But I don’t love the character of Nikita for her skills or her looks. Underneath the style there is the growing realisation that there should be more to life than what society demands of her. She is given a cover story, a flat, money, and in living that normal life she discovers she wants love, and hope. A future without killing.

I think sometimes the coolness of Nikita is remembered more than the message. But even if you watch it just for the slick direction and the shoot-out scenes, it’s still a great film. And the soundtrack, by Eric Serra, is perfect.

Three Colours: Blue (1993)

Julie (Juliette Binoche) loses her composer husband and her young daughter in a car accident, and decides to divorce herself completely from her old life, burning her husband’s final musical work, leaving the family home, taking no mementoes apart from one mobile of blue circles that once belonged to her daughter. It’s such a raw and personal film that it’s difficult to describe it further – watching it is akin to feeling Julie’s grief, and her desire to escape it. But it’s also an uplifting experience, and it finishes on a note of amazing positivity.

Blue is the first of a trilogy of films by Krzysztof Kieslowski on the subject of modern France, and its national motto of liberté, égalité, fraternité. It asks the question – is it possible to be truly free from the past, and from the emotions that are provoked by other people? Julie struggles to unchain herself from her grief, but the people who surround her tie her to the world, and to her loss. That tie is represented symbolically throughout the film, and the use of colour and music brings a new level of artistic meaning. It’s a beautiful, cohesive film.

The cover of the US release DVD shows a quote from the New Yorker, reading, “Mysterious…sexy!” which seems to me to be the exact opposite of the film. If ever there’s a film that doesn’t merit exclamation marks on the cover, it’s Three Colours: Blue.

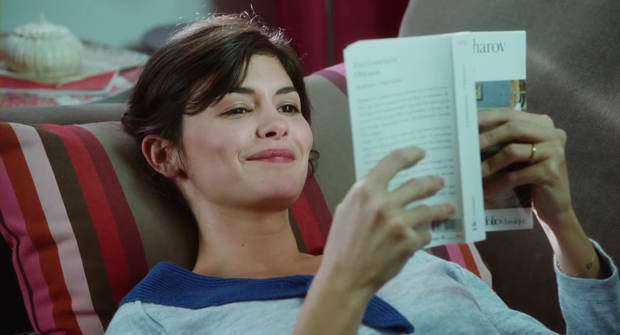

Amélie (2001)

There’s not a better feelgood film in the world than Amélie. Director Jean-Pierre Jeunet creates a sense of fun and hopefulness for the future in this tale of a young woman who devotes her life to helping others. Idiosyncrasies are cherished, and weirdnesses celebrated, and Audrey Tautou defines adorable for a whole new generation. She embodies Amélie, and so it’s strange to think that the part was written specifically for Emily Watson, with an original title of ‘Emily’. I think that would have still made for an excellent film, but a very different one in tone.

Amélie is all about not being afraid to get out and meet people, to be part of life. So next time you meet someone new, ask them what their favourite film is. You can tell a lot from the answer. If they obsess over The Seventh Seal chances are they’re not going to be such an upbeat person. But if they say Amélie you know you’re going to get on with them. It would be impossible not to, right? And they might even own a garden gnome or two.

Hidden (2005)

The voyeuristic quality of filmmaking has been tackled in many ways. Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom and E. Elias Merhige’s excellent Shadow Of The Vampire come to mind. Michael Haneke’s Hidden deals with the act of watching, recording, and playing back in a very cerebral way, but it’s still a chilling piece of work.

Anne and Georges Laurent (Juliette Binoche and Daniel Auteuil) live in a great apartment and have jobs they enjoy. But there is a tension between them, and that only grows when video tapes start arriving that show the outside of their apartment. This feels sinister, and even though there’s no obvious threat, it becomes difficult to live under the pressure of being examined. They live a privileged life, but they reach the point where they can no longer pretend that the outside world, the watcher, does not exist.

This isn’t a thriller, and as with any Haneke film there’s not much point in expecting a resolution. He’s not going to tell you what to think or even what he thinks about contemporary living. But he does make you examine it, objectify it, just as Anne and Georges are being objectified. It’s a film that makes you realise that, nowadays, nothing is really hidden at all.

Chrysalis (2007)

I mentioned earlier that Eyes Without A Face has been a hugely influential movie. Here’s another film that owes a great debt to it, except this time it’s been updated to the digital age with lots of panache.

We’re in Paris in 2025, and it looks all film-noir-ish and moody. Our hero is a policeman (Albert Dupontel) who is investigating the death of an illegal immigrant. The trail leads him to a deeply scary plastic surgery clinic that is not only concerned with faces. It’s quite happy to tamper with your memory and identity as well. There’s a very good performance by Marthe Keller as Professeur Brügen, the plastic surgeon.

Chrysalis is a polished movie that asks some very pertinent questions for our generation – it’s also proof that it is possible to revisit classic films and update them in such a way to make them fresh, without doing injustice to the original.

Delicacy (2011)

Audrey Tautou plays Nathalie, widowed after a short and extremely happy marriage, throwing herself into her job to try to escape her emotions. This works very well until she kisses one of her co-workers, an extremely tall and awkward bearded Swedish guy called Markus (François Damiens), for no reason that she can fathom, and the two of them have to work out if they’re attracted to each other or in a relationship at all.

Delicacy isn’t a romantic comedy. It is very funny, and charming, and the leads have great chemistry. But it’s not traditional sexual chemistry, and we’re not talking about a great love here. It’s about what waits for us once great love has gone – the importance of friendship, and companionship, and being able to laugh. The direction is subtle and low-key; it enables us to immerse in the story.

And the last thing I should say about it is that it has a wonderful ending.

Follow our Twitter feed for faster news and bad jokes right here. And be our Facebook chum here.