10 Wonderful Powell & Pressburger Films From the 1940s

Emeric Pressburger and Michael Powell brought us so many memorable moments from 1940s cinema. Here are 10 examples...

If you picture Britain in the 1940s, you’ll probably think of spitfires, military uniforms, London being bombed, rationing, dances, and hard times. You might also think of images that spring from the films of Powell & Pressburger. An RAF pilot standing at the foot of a staircase that stretches upwards; a dancer in red ballet shoes; aircraft flying through the night: in a run of ten films, writer Emeric Pressburger and director Michael Powell left us some of the most iconic scenes ever captured.

Here’s a look at all of those films. Some are incredibly well known, and others rarely get a mention. But they all have at least one moment where you look at the screen and say to yourself – there. That’s cinema at its best.

Contraband (1940)

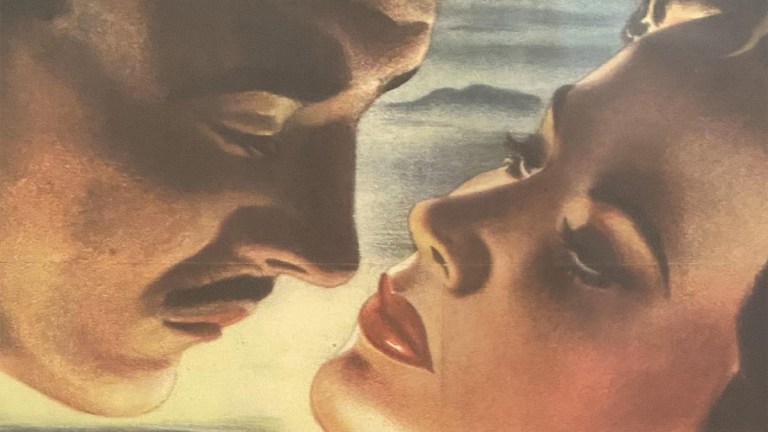

In the US this film was called Blackout, and apparently Powell preferred that title. It is a very black film, in terms of setting and in the comedic tone, helped along by two great performances by Conrad Veidt and Valerie Hobson. They have a sparky, even-handed chemistry that’s exciting to watch. Veidt is a steely figure, playing a Danish naval captain who chases a female passenger when she steals a motorboat and flees to London on espionage business.

Conrad Veidt was well known as a horror star, and in his late forties when he was cast here, and I think that really adds something quite different to what is essentially a romantic adventure film with some predictable spy stuff thrown in. It’s a curious piece of work – seek it out, and see whether you love it or hate it. And watch out for the cocker spaniels, who get a moment of fame. They’re called Erik and Spangle, and they appear in quite a few Powell and Pressburger films, because they belonged to Michael Powell. They’re lovely.

49th Parallel (1941)

There are no such issues with tone in this piece of propaganda, made with the express purpose of frightening the Americans into joining World War II. It’s really the opposite of Mrs. Miniver (1942); not about plucky Brits back home, but about six German sailors who escape their sinking U-Boat and end up on Canadian soil. They plan to flee across Canada to the neutral US border, and meet a diverse cast of Canadian citizens along the way, who represent everything the Nazis hate.

Laurence Olivier kicks it all off as a French-Canadian trapper, and it’s a huge performance, which is not to everybody’s taste. But here’s the thing – he’s just bigger and bolder and brighter on the screen, and he brings his own energy, enlivening the film. This is one of the best examples of a film that thrives on bit performances by great stars – Anton Walbrook and Raymond Massey also excel – and perhaps the forefather of that model of cinematic epic, such as A Bridge Too Far (1977). When you’re not on screen for long, you have to really make it count, and Olivier certainly does that.

One Of Our Aircraft Is Missing (1942)

So this is a mirror-image of 49th Parallel, telling the tale of six British airmen who are forced to bail out over the Netherlands, and find a community under Nazi rule who will risk their own lives to get them back home. Pressburger wrote some beautiful dialogue here about what it’s like to live under oppression; he had fled the Nazis in 1935, and throughout his career as a writer he just got better and better at explaining what it’s like to come to a strange country, and learn to love it for what it represents, even while your home country is tearing itself apart.

Peter Ustinov makes his film debut as a Dutch priest, and gets a few lines. Thirty-three years later he appeared in another much loved British film that played on the title, One Of Our Dinosaurs Is Missing (1975), along with actors who had also worked with Powell & Pressburger, including Kathleen Byron and Hugh Burden. It’s good to think that title had become so well known; this film, and 49th Parallel, just show the determination and drive in the British film industry at the time to make stirring, memorable films. It’s impossible to watch them and not feel moved.

The Life and Death Of Colonel Blimp (1943)

Here’s where the business of propaganda gets interesting. This isn’t a straightforward film, although I find it intensely patriotic in places. But it’s not a patriotism born of war, but of what is left after war, and how we move on from such terrible times.

A far-reaching, fantastical view of a life punctuated by two world wars, Colonel Blimp has everything: comedy, tragedy, romance, thrills, and quiet contemplation. Churchill took offence to the bombastic lead character and apparently tried to get production stopped. It was heavily cut, release was delayed, and generally it went through some tough times until it was reconstructed in its original form, thanks to the efforts of filmmakers such as Martin Scorsese. Pressburger thought it was his best film, and I have to agree. It has the most amazing structure, and it contains one of the best speeches ever written about England, which is delivered perfectly by Anton Walbrook.

A Canterbury Tale (1944)

From the big budget, Technicolor brilliance of Colonel Blimpto a very weird story of a Kent village in which a mysterious figure leaps out of hedges at night and pours glue in young ladies’ hair.

It’s a very small mystery played out against the backdrop of the war, bringing a very personal feel to the screen. The critics mainly hated it, but it has since inspired its own band of followers, and there are even organised walks around the Canterbury locations. It’s not hard to see why; it captures something about the British way of life that had rarely been seen on screen at that point – namely, our ability to go along quite equably in the presence of something really bonkers.

A Canterbury Tale also has one of my favourite match cuts in it (when two similar images are edited together to give an extra level of meaning to the viewer). Perhaps the most well known match cut is in 2001, when Kubrick gave us a bone being thrown into the air, and then an immediate cut to a space station. Possibly he got the idea from A Canterbury Tale, where a falcon becomes an aeroplane, and the same face looks up at them both. Hundreds of years are traversed in a moment, and we have to ask ourselves – in that time, what has really changed?

I Know Where I’m Going! (1945)

Emeric Pressburger wrote some great female characters, including the lead in this tale of romance against the odds, and against everyone’s wishes, in the Scottish highlands. Joan Webster knows exactly what she wants out of life, but life itself conspires against her. She’s played by Wendy Hiller, who gave a number of performances in which the voice remains clipped and brittle, but there’s an astonishing amount of emotion in her eyes. It’s also worth checking her out in Pygmalion (1938), Outcast Of The Islands (1952), and The Elephant Man (1980).

Lots of people really love this film. There’s something so enjoyable about the unstoppable force meeting the immoveable object, and the idea that love will control your destiny, no matter what you think about it.

A Matter Of Life And Death (1946)

The film critic David Thomson wrote that this film is about, “…a shattered mind and anything and everything can stroll in and out as the synapses flap in the breeze of concussion,” which really made me look at it afresh. Is it really all about what’s happening in Peter’s (David Niven) head? I prefer to see it as another instalment in Powell & Pressburger’s major theme of love conquering all, but it also sows the seeds of the harder, more psychologically challenging films that they began to make soon afterwards.

Still, however you look at it, the freedom that the plot of concussion and brain surgery gives is fully exploited; we get two worlds, one in Technicolor and one in black and white, and time can stand still, and people can survive plane crashes without a parachute, and anything is possible. When you look at it in those terms, it’s almost like a version of The Wizard Of Oz, except here Kansas is Britain looking more beautiful than anything that could be found in the other place. Never has a British beach looked more gorgeous.

Black Narcissus (1947)

Leaving the war behind and venturing further into strange new territory, Black Narcissus is just so vibrant. It’s overpowering in its colours and patterns, all of which reflect a sensuality that a group of nuns living in the Himalayas are trying their hardest to repress. But one of them will be driven mad, and murderous, by this land of astonishing flowers and stirring breezes.

It must be a great experience to watch this on the big screen, particularly the climax, which is shocking and scary and bizarre. It was a big influence on Hitchcock, particularly in the final scene of Vertigo (1958). Basically, looming nuns are scary. But, beyond that, there’s the feeling that we are being sucked into an entirely different world, where we can’t escape its vibrancy, and it will overwhelm us. Which leads us nicely on to…

The Red Shoes (1948)

It seems we really can’t get away from those burning emotions, and in The Red Shoes it’s the incompatibility of love with ambition that drives the lead character, Vicky Page (Moira Shearer) to despair. Here is the perfect fusion of cinema and ballet; the way the camera slows the dancers, and follows their feet, and turns every aspect of experience into choreography.

In Britain rationing and austerity was still a hard reality at the time the film was released, and there was a general feeling that such lush explosions of cinematic adventurousness were out of keeping with the rest of the country. But the US loved it, and it paved the way for films such as An American In Paris (1951) where a full-length ballet sequence, a riot in movement, could hold audience attention. Of course, it receives its due now, with pretty much everyone in agreement that its an incredible film. I can’t think of a more beautiful one.

The Small Back Room (1949)

Powell & Pressburger ended the decade by returning to the familiar: the war film. David Farrar (who generally never seemed to get very interesting parts) shines as Sammy, an analytical scientist working for the government during World War II. He has an artificial leg that pains him greatly, and he takes pills and drinks to get through the day, and he says terrible things to his long-suffering girlfriend. Basically, he’s the forerunner of Gregory House. But a time comes when he has to become the hero, no matter how much it hurts to do so.

Back in black and white for this one, and Powell gives us some expressionistic sequences that bring Hitchcock to mind once more. The ticking clock that looms, the beads of sweat on the forehead, and the way Sammy’s flat (the small back room of the title) changes in the grip of his addictions make for great cinema. Also, this film has one of the most tense and drawn out bomb disposal scenes I can think of. You feel an emotional wreck yourself by the end of it.

A complete change from the films that had gone before it, The Small Back Room ended a decade-long run of ten films from a writer/director collaboration that was astonishingly productive. To look down that list of films and to think they were made one after the other is, quite simply, mind-boggling. Powell & Pressburger made eight further films together, but this was their golden period. A golden decade – how lucky we are to have their films as a reminiscence of that toughest of times, but also as a way of looking at the world that once was.