Revisiting A Matter Of Life And Death

It’s 71 years old and considered one of the best British films ever made. Rachel takes a look at the wonderful A Matter Of Life And Death.

This article contains spoilers for A Matter Of Life And Death

It never made sense to me that they changed the title of A Matter Of Life And Death for American cinemas (it was thought that US audiences wouldn’t go and see a film with the word ‘death’ in the title); Stairway To Heaven feels wrong for a couple of reasons. Not to be pedantic but technically it’s an escalator, also it’s never explicitly referred to as ‘Heaven’ in the movie. But mainly, it’s far too imposing a title. Part of the film does explore the afterlife (and it doesn’t get much more imposing than that…), but what’s so brilliant about A Matter Of Life And Death is how it effortlessly segues from the awesome to the intimate, never more beautifully captured than in the idea that that a single tear might stop eternity, all in the name of love.

71 years after its premiere, A Matter Of Life And Death is back on the big screen in a shiny, 4k restoration. AMOLAD (as it was affectionately known by its creators) is Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s most well-known work and a perennial entry in ‘Best British films of all time’ lists, but what makes it so beloved?

“This is the universe. Big, isn’t it?”

For those who are unfamiliar, AMOLAD is the story of Squadron Leader Peter Carter (David Niven) who we meet in 1945 as he’s trying to pilot a damaged Lancaster bomber over the English Channel. On his orders Peter’s crew have bailed out but his own parachute has been ripped up, leaving him with no option other than to jump without one. Then, in what has to be five of the finest minutes ever committed to celluloid, Peter radios in to June (Kim Hunter), an American radio operator based in England, before jumping from the plane and to an almost certain death.

However, Peter survives when the Conductors from ‘The Other World’ lose him in thick fog over the English Channel. Peter meets up with June and the two fall in love until Peter starts having visions of a French Aristocrat called Conductor 71 (Marius Goring) who tries to retrieve him but Peter refuses, prompting an other-worldly court case that Peter must win to stay with the woman he loves.

“One is starved for Technicolor up there.”

The story goes that AMOLAD started life as a bit of wartime propaganda. The Ingsoc-ian sounding Ministry of Information was the government department responsible for publicity and propaganda during both World Wars and frequently worked with film makers to look at their films and give suggestions as to how they could include positive messages about the war effort. Although Powell did go on to say he found them “wonderful to work with”, Powell and Pressburger had incurred the ire of the ministry following their 1943 film, The Life And Death Of Colonel Blimp. The ministry had expressed their displeasure at the representation of the military in Colonel Blimp, going so far as to refuse to release Laurence Olivier from his role in the Fleet Air Arm (a branch of the British Navy) to play the lead character despite him being Michael Powell’s first choice.

AMOLAD, however, was born of a suggestion from Jack Beddington, Head of the Ministry of Information, to “make a film to show the Americans we love them”. At the time there was the mood in Britain was one of resentment towards the American GIs stationed in the UK who were “overpaid, oversexed and over here” and the Ministry wanted to change that, so what better way to do that than with the story of a dashing British Officer sweeping a beautiful American girl off her feet?

It was a pricey venture, costing £320,000 (about £12,700,000 in today’s money), a huge amount at the time, particularly in wartime Britain. AMOLAD had an extended pre-production period whilst the escalator that acts as the link between earth and the other world was being built under the code name ‘Operation Ethel’. Constructed under the supervision of the London Passenger Transport Board, ‘Ethel’ took three months to make and cost £3,000 (£119,000 today), and all the dialogue shot on the escalator had to be dubbed in post-production because her machinery was so loud.

Just to add to the difficulties, there was a nine-month wait for film stock and Technicolor cameras because they were being used to make army training films. The choice to film partly in colour, partly in black and white meant that Jack Cardiff had to come up with his own way of processing the film so the transitions between Earth and the other world were seamless (this process called ‘Colour and Dye-Monochrome processed in Technicolor’ has the serendipitous effect of giving the monochrome scenes a pearly sheen).

There’s so much more in this movie that was headache inducing for the people who made it. Seemingly every aspect of production brought with it some kind of complication which makes it all the more impressive that the end result is as gorgeous as it is.

“I love you June, you’re life and I’m leaving you”

First and foremost A Matter Of Life And Death is a love story. For all the readings and all the subtext it simply would not work were it not for the central performances of David Niven and Kim Hunter. Niven at his most twinkly eyed and witty and Hunter a kind, beautiful girl-next-door, are irresistible; you can’t help but get drawn into their relationship. Theirs is a whirlwind romance that would seem implausible were it in any other film than this, they’ve known each other for a minuscule amount of time but it’s a testament to the movie that that isn’t jarring at all.

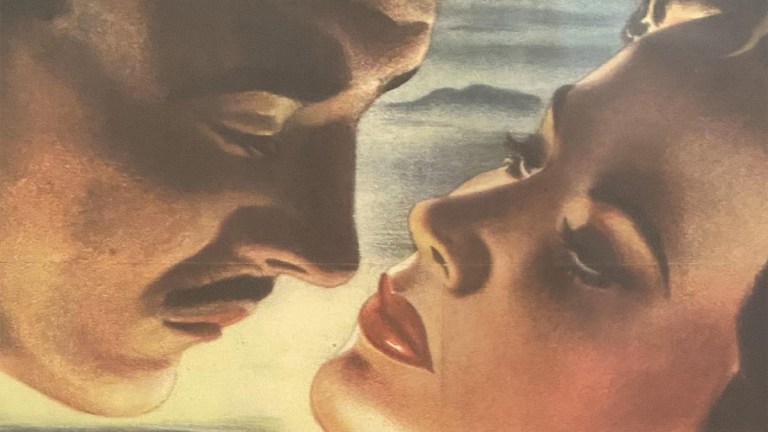

I think this is down to those opening five minutes when Peter radios June. It’s such a beautifully crafted scene; the extreme close ups of their faces, the immediacy of the back and forth between the two; intense and gorgeous, that scene binds those two characters in a shared experience which makes their love for each other so believable.

“Here in this tear are love and truth and friendship. Those qualities and those qualities alone can build a new world today and must build a better one tomorrow.”

What makes AMOLAD so great is how effortlessly it blends ostensibly contradictory ideas together in a way that feels completely natural. The film never makes a decision regarding whether or not Peter’s hallucinations are real, giving equal weight to the medical reasons for Peter’s condition as well as the spiritual. Two ways of thinking, so often pitted against each other, here allowed to be presented side by side.

The film seems to focus on the rights of the individual, as Dr Reeves explains “the rights of the uncommon man”, but there’s plenty of evidence to suggest it’s as much about the rights of all humanity. As the fallen airmen arrive at The Other World and the clerk informs them that “we’re all the same up here”, the idea of equality is peppered throughout AMOLAD. During Peter’s trial Dr Reeves asks that the jury made up of different nationalities be replaced by one entirely made up of American citizens. So a new jury is brought forward, a jury of many races and accent but all citizens of the same country. As with all the best films, AMOLAD is still as relevant today as it was 70 years ago.

“Yes, Mr. Farlan, nothing is stronger than the law in the universe, but on Earth nothing is stronger than love.”

I think it’s possible that the more cinema you consume, the less inclined you are to say you have a favourite film. That’s understandable, there are so many movies released each year you never know if something is going to supersede whatever you thought was the best or you’ve simply seen so many that you love for different reasons it’s impossible to choose. But I think it’s more than that – there’s vulnerability in sharing what you love. However, in a time where the perceived wisdom is that people like us live to pick films to death and never have anything nice to say, I feel like we’re losing something when we don’t talk about what we love.

A Matter Of Life And Death is my favourite film. I realise it’s hardly a risk to confess that a film beloved of critics, filmmakers and movie fans is your favourite, no one’s going to laugh me out of anywhere, but I still think it needs to be said.

When I watch A Matter Of Life And Death I can see all the technical and artistic things that make it great. I see everything I know about its production, the talent of the people who made it, the glorious Technicolor, the gorgeous script and impossibly charming performances. But there is something more sublime than that woven into the fabric of this film.

When I watch A Matter Of Life And Death I see how it makes me laugh when I’m sad and its uncynical romance that melts my heart every single time. I see the ability movies have to transcend, to move and shape us and change who we are. There is an elusive magic at the heart of this film that I am yet to find in anything else. It is my cinematic soulmate and I cannot wait to see it on the big screen.

A Matter Of Life And Death is in selected cinemas across the UK from 8th December.