Myst: Creators Rand and Robyn Miller Unlock the Secrets of the PC Classic

Rand and Robyn Miller talk to us about revisiting the revolutionary game Myst for a new making-of documentary from Philip Shane.

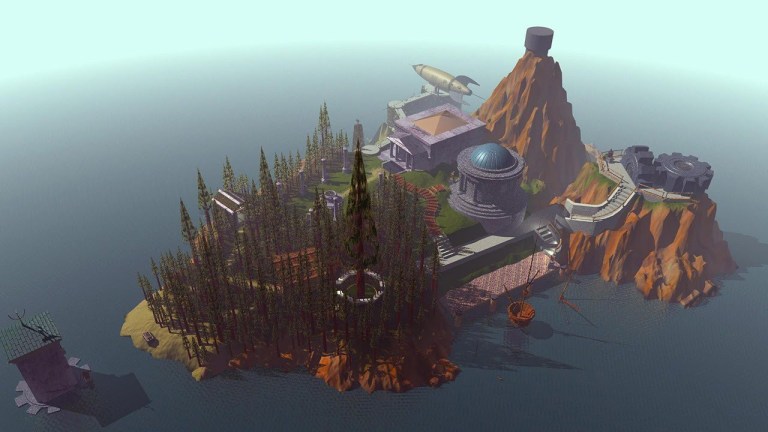

In 1991, two brothers—Rand and Robyn Miller—along with a handful of artists and engineers, set out to create a game unlike anything that had come before it, harnessing powerful new PC technology to immerse players in a fantastical island world inside a book. The game was called Myst, a point-and-click adventure full of infuriatingly difficult puzzles and driven by a twisted, fantastical story about a tragically dysfunctional family

Released in 1993, the game was lauded by fans and critics alike, became a killer app for CD-ROM drives, and went on to become the best selling PC game ever (over 6.3 million copies sold by 2000) until The Sims dethroned it in 2002. More than two decades after its release, there are even plans to turn the game into a movie and TV series. Myst is one of the most unlikely commercial success stories in gaming history, particularly due to the fact that the game was so strange, so notoriously difficult, and was made by such a small team (Cyan Worlds, founded by the Miller brothers in 1987).

“I was more of a gamer than Robyn, but both of us settled with Myst on the idea that, well let’s not have people die and start over, because that irritated both of us. We felt like we were building a real world, and in a real world, you don’t just die and start over every five minutes.” Rand says of the initial conceit that led to the creation of the game. “We wanted to add friction that would slow you down but we didn’t think that there were rules to video games necessarily, so we’ll pull out the dying and see if we could do it without that.”

Indeed, there’s no dying in Myst, a revolutionary idea at a time when “Game Over”s were a staple in virtually every game on the market. Instead, Myst tasked players with exploring its world and decrypting its story, eschewing combat for puzzles that challenged and engaged you but weren’t life-or-death ordeals.

“I’d love to tell you we knew exactly what we were doing, but we didn’t,” Rand says. “It was just another experiment along the scale of how to make things a little more sophisticated, and even within the game itself, you can see how we were expanding and building more cohesiveness into the worlds as we went.”

Despite its humble origins, Myst was a huge deal for a lot of people in the ‘90s, including me. I remember the thrill of watching it run on the new PC my parents bought for me and my brothers in the mid-90s, marveling at the FMV elements combined with the detailed pre-rendered environments.

“For me, Myst was for games what Star Wars was for movies,” explains Philip Shane, a filmmaker who’s launched a Kickstarter for a documentary about the making of the PC classic. Shane previously co-wrote the Sundance Special Jury Prize-winning documentary Being Elmo (2011). “I was 10 years old when Star Wars came out and, in my mind, I was the same age when I played Myst. Just like with Star Wars today, when you look back on Myst, it was the first time you ever saw something with that level of detail. It was an odd game, but for me it was huge.”

Myst is responsible for a wave of cinematic, immersive games with rich storytelling that are as popular in 2020 as they ever were. Games like The Witness, Outer Wilds, and Quern draw inspiration from Myst’s original puzzle-adventure formula, while Dear Esther, Gone Home, and The Stanley Parable are heavily influenced by the world-building and environmental storytelling Myst pioneered.

“I think in our minds, it does feel like we’re building worlds and not necessarily games,” says Rand of Cyan’s approach to making games. “We try so hard to create this consistent flow in our worlds. It’s not easy. It takes a lot of effort to tie the environment with the story and the puzzles. It’s not always perfect. But we make that attempt to make it seem viable as far as worlds go.”

“And so we started coming up with [Myst’s] backstory,” Robyn adds. “And it helped to give us a better understanding of the entire world and maybe a better understanding of where the world should move onto for where we were going with it. We filled out the details, the empty spaces in our minds.”

Rand says that The Lord of the Rings books by J.R.R. Tolkien were a particular inspiration when building the world of Myst.

“[The Lord of the Rings] felt like you’re just reading one of the books, but the world was much bigger than that. It felt like you had a window. You were just experiencing a small window into a much larger world. And for some reason, that really resonated with us.” Rand explains. “That made those worlds seem so much more real to us. And so, when it came time to do our worlds, that’s naturally where we land. We build backstory and wrapped stuff around the family and what had happened. Stuff that didn’t even need to be told in the little window of the Myst game. But in our world, it gave it weight and I love that.”

The brothers also credit Alice in Wonderland, Tintin comics, and Jules Verne’s The Mysterious Island as major influences on Myst.

“We had a couple of months to design the thing, and so it was more of a regurgitation of everything we had collectively in our psyches and aesthetic selves and whatever those influences were,” Robyn says. “Tonally it created something that was mysterious and weird, but it was all these things pressed together into this weirdness.”

Myst’s central tale, of Atrus and his warring sons Achenar and Sirrus, stretches far beyond the original game, to tie-in novels and its four sequels (one of which was developed by Ubisoft independently). Due to budgetary restrictions, Rand and Robyn were forced to act in the game themselves, with Rand playing Atrus and Achenar, and Robyn playing Sirrus (Rand continued to play Atrus in the game’s sequels).

“I would not call it acting,” Robyn says. “The fact that we got anything that looked good out of what we did is a miracle. It was just me and Rand really, and the thing I remember most is that we were laughing hysterically through it.”

“Like Robyn said, it’s a wonder we got anything out of us,” Rand says. “Looking back, in spite of the fact that we would not have cast ourselves had we had a real budget and to do things the way we wanted to, it’s cool again that we as brothers got to play those brothers and look back and laugh at it. I’ve got tapes.”

Though he was a longtime fan of Myst, Shane had never thought to make a documentary about the game until he met with the Miller brothers at a games convention in 2016, where they were presenting a keynote. At an after party, he approached them as a fan, without an inkling that the ensuing conversation would launch him into the next stage of his career.

“I was terrified,” Shane recalls of meeting the Millers. “I went up to them and immediately I thought, ‘Surely someone has made a documentary about Myst.’ So I said, ‘Has anyone ever made a documentary about Myst? And they were like, ‘No.’ And so I was like, ‘Could I?’ And they were like, ‘Really? Yeah.’ In spite of the making of Myst being a 25-year-long story, this was the fastest I’ve ever gone from conception of a documentary idea to green light. It was as fast as the neurons of three people could go. Just a couple of weeks later, my camera person, my cinematographer Kyle Kelly, and I flew out to Spokane and started filming.”

Spokane is the home of Cyan Worlds and the birthplace of Myst, its sequel Riven (1997), spiritual successor Obduction (2016), and the forthcoming Firmament, the studio’s first major VR release. Shane remembers watching a short, grainy documentary clip of the brothers talking about the making of Myst on a disc included with the original game’s release. “There were these two guys making the game at home,” he recalls. “At one point, the camera pans away and you see all these trees. I was like, ‘Those are the trees from Myst.’ It was like they lived in the game.”

With his documentary, Shane endeavoured to delve into the lives of the Miller brothers on a personal level, which meant spending a lot of time talking to them and picking their brains. Looking back on the making of Myst over a quarter of a century after its release has been an unexpectedly profound experience for Robyn in particular, who hasn’t been involved in making video games hands-on for decades now. Robyn left the company after the release of Riven in 1997 while Rand stayed on as CEO of Cyan Worlds.

“Well, I’d forgotten about Myst,” Robyn says of revisiting the game almost 30 years later. “If I play Myst today, it’s like I’m actually playing Myst [for the first time] and I have to remember things. It’s weird. I haven’t worked on any of that stuff in such a long time, so it’s fun to talk about Myst now.”

Shane says he has every intention of going through the brothers’ archive of tapes but that the success of the Kickstarter will largely determine how much he’ll be able to comb through for the documentary. “Research for a documentary is more time-intensive and expensive than people might know,” he explains. “And a big part of it is time. The more successful we are with the Kickstarter, the deeper I’m going to be able to go [into the archives]. I can’t promise anything, but I want to get that stuff. Rand has a ton of home movies. They both have a lot of stuff that they’ve saved up.”

Currently, Cyan is hard at work on its forthcoming puzzle-adventure game, Firmament. The studio is deep into development, and while Cyan originally targeted a July 2020 release date, the COVID-19 pandemic caused the team to push the release back, announcing in a recent Kickstarter backers’ update that the game likely wouldn’t be finished until 2022. But the team is still working hard on the game from home, and according to Rand, they were largely prepared to work remotely and continue development.

“Firmament‘s probably one of the best storylines we’ve done in a game since I’ve been doing this. It’s really cool,” Rand says. “Whether we can pull it off, I think, Robyn and I talked about this so many years ago is, even for Myst and Riven: you can have big plans for a story, but at some level, it’s about being able to communicate it. Sometimes you just have to simplify it so that it’s satisfying and people get it. So we’ll see what we can do with Firmament, but it’s a great, great storyline.”

When it does arrive, Firmament will be the latest in a long line of memorable experiences from Cyan Worlds. But Myst will always be their crowning achievement, a game that continues to impact its players today. The Miller brothers admit that Myst grew beyond anything they could have possibly imagined.

Robyn puts the enduring legacy of this game best: “We made Myst and we never expected it to continue on this many years later especially. Now it’s so much larger than Myst. It’s got a life of its own. There are so many people who are involved in — whether it’s creating, writing their own stories about it, or painting pictures, or having guilds, or the Mysterium [an annual celebration of the game] getting together every year. It just goes on and on and on, it’s this world that exists out there. This massive thing that is much larger than the Myst games. We feel privileged and humbled to be a part of that, privileged and humbled to have been there at the beginning.”

Shane’s The Myst Documentary is currently in pre-production and will cover both the origin of Myst as well as the current work being done at Cyan Worlds. The project has more than 2,000 backers as of this writing. Check out the Kickstarter here.