30 Years Later, EarthBound Is the Game That Grew With Us

More than a case of nostalgia, understanding the brilliance of EarthBound requires you to look back at it from an adult's perspective and through a child's eyes.

It’s not as easy to ignore the impact of the 1995 SNES RPG EarthBound as it used to be. Released in America to low sales and a somewhat confused fanfare, including a Monty Pythonesque ad campaign built on self-deprecation and fart jokes, it was a game known mostly to the nerdiest and yet most experimental of that first mainstream gamer generation. They would try to tell their less dorky friends about it in the hushed but reverential tones of a French New Wave film student, but nobody had seventy bucks to blow on this fever dream of a game simply based on the weird kid’s endorsement.

These rambling adorations did add to the mystique of EarthBound back then, if not its sales: America itself, idealized as a truly whackjob Eagleland (a concept funnier than ever), kung fu children, psychic powers, and some gruesomely eldritch final threat that these kids, usually not yet exposed to Lovecraft, couldn’t elucidate. It took 1999’s Super Smash Bros to get players to discover that Onett’s hometown hero Ness really was a kick-ass little chap in short pants, and by then, you had to either get lucky at FuncoLand, or get wise to the digital underground.

Those who managed that feat were now late teens or older, moving on past the weird kid era and into the liminal nightmare of the twentysomething. Like a Spielberg movie, or Stranger Things, before that series got too long in the tooth, maybe that was the rest of the trick EarthBound needed to become something more: a mind with just enough maturity to see past the poop jokes, and an inner child that remembered the glories buried in the insanity of being a ten year old.

These Are the Kids of America

There’s nothing completely normal about the world of EarthBound, and its makers had no earnest, lived experience with being a Stateside suburban kid in the ‘80s and ‘90s. Yet writer Shigesato Itoi intuitively grasped something about the soul of the experience, finding some universal echo within his own childhood. Half-remembered nightmares and the strange, liminal emptiness of being a kid with parents who loved you yet lived at a distance, and all. Helping him is translator Marcus Lindblom, who took the universalist childhood Itoi offered and gave the Western version its American in-jokes and absurdist moments of combat text. The result is harmony; two people succeeding in their intent of showing just how fucked up, yet totally joyful, being a kid could be.

Ness is, genuinely, just a kid. His mother is in his life as at least a routine figure that makes sure he’s fed and well rested during his travels. His dad is never seen. He sends money home (and into Ness’ account), and gives Ness the pep talks he needs to hear to carry on. But mostly these necessary authority figures are just sort of assumed to be there, loving but not invested in whatever mental world kids inhabit when their brains are still Silly Putty.

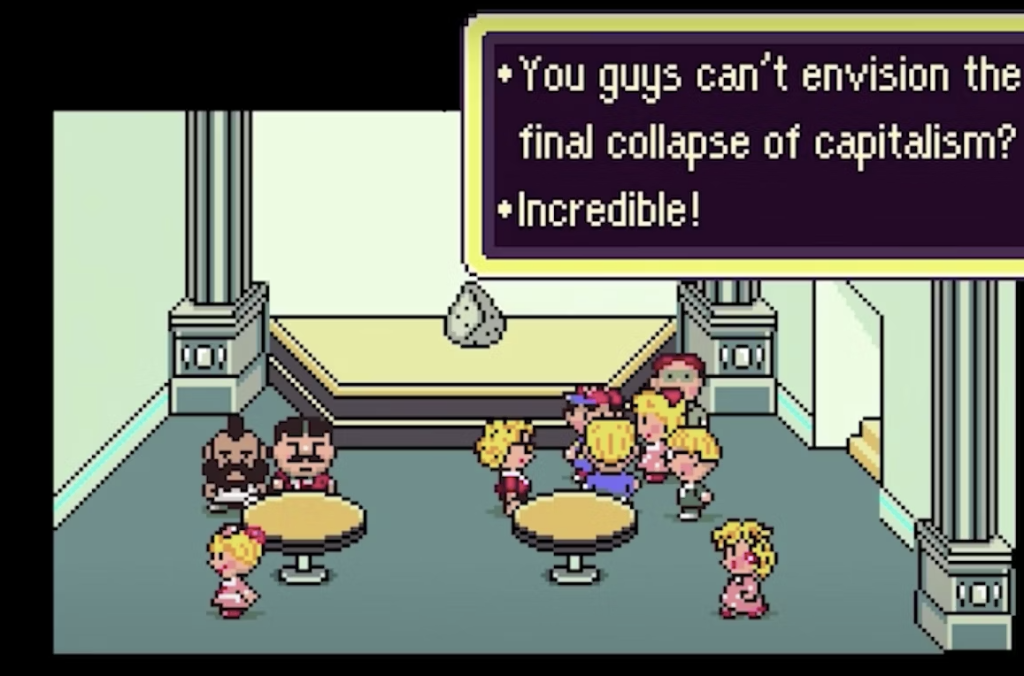

Like Stephen King’s IT (minus “The Weird Bit” near the end), Ness and his eventual companions, Paula, Jeff, and the Poo, are tuned into a version of the world adults couldn’t dream of. It impacts those adults, occasionally, and a number of them are liars or screwed-up dreamers in their own right, proving the child’s safety adage: you can’t just trust strangers. But mostly it’s left to the children to venture forth and figure out what the hell Buzz-Buzz, the now-deceased time traveling bug, was trying to warn them about. With all of that impossibility in their corner, it’s no surprise that the magic system these kids grow into is based on psychic powers, a field of mysticism that favors the most willful and imaginative.

It all comes together in a straightforward enough premise for one of the strangest RPGs of all time, from the call to adventure to the gathered party and onward to the final showdown. But by setting the game in a version of America so absurdist that it’s oddly familiar to those of us who grew up in that lonely, post-Reagan latchkey kid era, EarthBound becomes something more. It’s about how we lived like survivalists in our own houses, our only back-up a tenuous landline phone connection to our mom’s office or our dad’s retail gig, trying to cadge money for a thirty minutes or it’s free pizza tomorrow if we start the laundry tonight.

We were brats left home alone with a keyring, a microwave, and our imaginations. Ness was the part of our imagination that just knew our tiny little butts could step up if aliens attacked our neighborhood while Mom was out. But what Ness learned, and what became important to us, too, was that… it really wasn’t going to be that easy, if bad things happened to us. And understanding why bad things happen might even be terrifyingly beyond us. What a lonely, scary feeling. It’s the secret heart of the Mother franchise, of which EarthBound was the second chapter.

EarthBound Reminds Us that Loneliness Kills

The most relatable aspect of EarthBound, when it comes to the horror and confusion of being a kid, lies in its villain, Giygas. The irony is that, back in ’95, Western players had no way to know just how heartbreakingly understandable that lunatic, screaming thing actually was, once. His decay into unearthly madness between Earthbound Beginnings (released as the original Mother) and EarthBound runs parallel to Ness, and that’s on purpose.

While the love of a Mother, always accepting even when distant, helps Ness through his journey, for Giygas, a mother’s love is ultimately both his only connection to ‘humanity,’ and the destruction of his fragile identity. It’s not that Giygas was always some incomprehensible thing, an Akira-level eldritch compilation of raw psychic power. It’s that he was loved, once, and that love caused this invading alien to make a choice, halting his revenge against the rest of humanity. At least for a little while.

As EarthBound unfolds, Giygas has lost himself to the all too human — all too childlike — spirals of guilt and rage, his adopted mother now far out of the picture. All he has are inhuman yes-men and a new childhood friend of his own. Unfortunately, Porky (we condemn the translation error in this house) is another Stephen King special, the bully with a cause. Like any malicious mean girl hanger-on, Porky doesn’t care about Giygas itself, and doesn’t think about maybe talking to it through its pain. To him Giygas is literally the almighty idiot, a thing that feeds his own spoiled cruelty. No wonder it’s Porky who goes on to become the main antagonist in Mother 3. Meanwhile, Giygas’s story ends in EarthBound, dying frenzied and unloved, destroyed by a pack of kids wielding the collective hope of all the people they’ve met and helped.

A Legacy Wearing Sneakers

For thirty years, EarthBound paved an asphalt road into the heart of what kids can be, with a vision of reality so skewed yet truthful to the spirit within that it’s on par with other landmark children’s tales like The Goonies and Explorers. There’s something special about the magic of childhood, especially when it’s honest about the darkness there, too. For modern video gamers looking to feel something familiar yet that they’ve never experienced before, you still can’t help but come to Onett, looking for its hometown hero. Even though he’s just a kid, like all of us used to be.

Is it frustrating for a long-time EarthBound fan to look back on how long it took the game to entrench itself in the gaming culture the way it deserved? No doubt, but maybe it was also necessary for the game to lie fallow for a while. It’s an experience at any age, certainly, but, like adults watching ET fly across the moon for the first time, maybe we gotta be able to reflect on these stories with older eyes. To a kid, every day is a refreshed exploration of wonder and bemusement. To an adult, and especially to the now forty-something generation that grew up with Ness, nostalgia isn’t just about loving bits of our past. It’s also about realizing just how batshit being a kid really was. Only EarthBound makes the journey of understanding with us.

The half-remembered childhood nightmare Itoi puts at the heart of EarthBound is a universally human experience on its own, and by using it in a story that became shaped into something uniquely American with the help of its localization team, it somehow locked into an aspect of the ‘80s zeitgeist that goes generally undiscussed by post-Reagan scholars and Wall Street wannabes. EarthBound is the Gen X game, once forgotten yet ever-present, affecting today’s gamers with a haunting psychic punch that says there’ll never be anything like this again. Not when today’s kids can’t even go to a mall without adults acting like they’re unwanted interlopers.

The Intergenerational Horror and Coolness of Our Existence

EarthBound’s impact on the RPG can’t be overstated, although God knows we try. It’s the first game to take the common tropes of childhood heroes and grand destinies and treat them like actual children would, hopes and horrors and all. It even did so with this wonky, dreamlike understanding of a country across an ocean, putting together Americanized tropes and too-adult references and fart jokes aplenty until its imagined world is as contrived yet dead on as Shin Megami Tensei’s mythology stew. And, just like the first time we saw a Persona game, wow, did this thing bomb at first.

Something about EarthBound still drills to the heart of America’s childhood, even if we’re decades past the latchkey loneliness and living in the bizarre “You Are Always On Camera” era. Something about the game’s messages about friendship, about finding the few other people in the world that will ride or die with you to the end, remain constant and fresh. It’s spooky to leave home, but with friends by your side, there’s always an anchor to help you find your way. Ness didn’t have WhatsApp to help him find Jeff in time to conquer Threed, and maybe it would’ve been easier to get Poo onboard via the martial arts TikTok community, but that harmonious feeling of people just finding each other in the noise of the world… yeah, that still matters.

Today we look for those same echoes in new generations of games. From Omori, which loses its predecessor’s bonkers joy in favor of a straightforward exploration of deep childhood depression, to Undertale, whose minimalist gimmicks hide a gigantic story about free will and the gift of mercy, there’s something about the heavy emotions of youth that can carry a story into places we rarely stop to consider. In every case, it’s the journey that matters, and the road that determines the destination. For thirty years, nothing’s told that story quite like EarthBound. Yet new generations keep trying, and honestly, that’s the best lesson the game could give us. Life is always our story. How we share it makes it everyone’s story. And if it takes a while for it to click? Don’t let that stop you from trying anyway. Your true friends will always have your back.