Wrong Man Criminal Defense Lawyer Ron Kuby Takes a Stand

Legendary civil rights and criminal defense lawyer Ron Kuby talks justice for Starz's Wrong Man, along with exclusive clips.

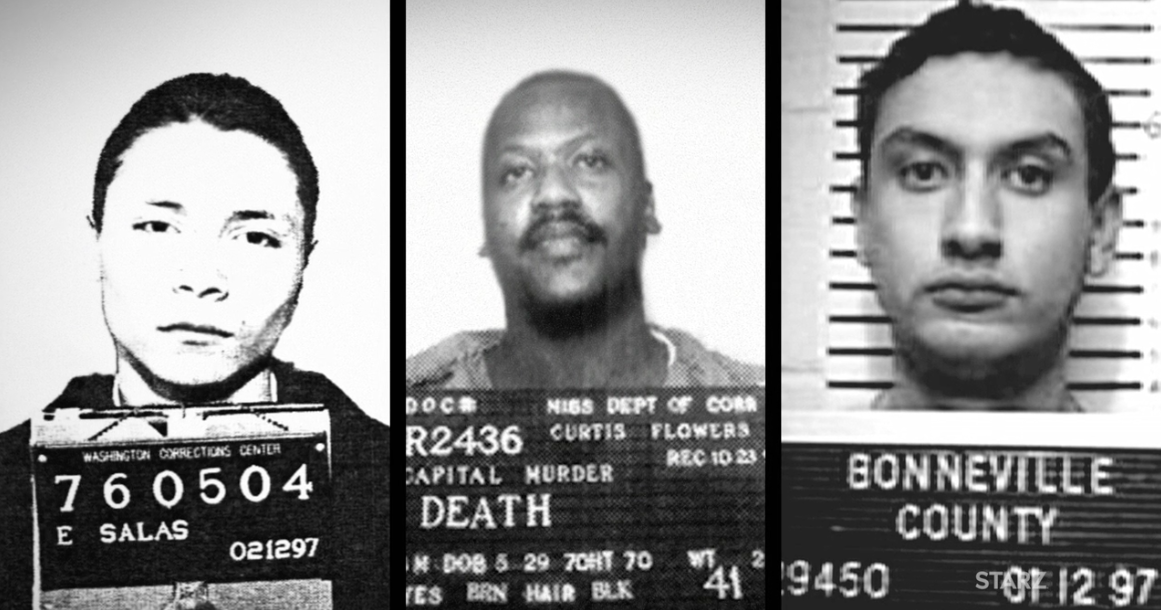

Starz’ Wrong Man isn’t a standard police procedural. Most cop shows focus on prosecution, most bad guys did some bad things. But the six-part documentary series from Paradise Lost and Judgment Day: Prison or Parole? director Joe Berlinger catches law enforcement cutting corners and sometimes deals which border on the criminal. Berlinger, who directs the first two episodes, asks former prosecutor Sue-Ann Robinson to breaks down the inside rules. And he put blue on blue, asking retired NCIS investigator Joe Kennedy and Detroit Homicide Task Force member Ira Todd to question the police. The legal team is guided by legendary criminal defense and civil rights attorney Ronald Kuby.

Kuby has been going after cops for over 40 years. He’s seen expedient arrests and prosecutorial misbehavior on many levels. He’s also a geek who likes post-apocalyptic science fiction like Battlestar Galactica and the works of When Worlds Collide author and subversive provocateur Phillip Wylie. Kuby is a born “againster,” from publishing anti middle-school papers to being deported from Israel before he was 20 years old. He had his arm broken during an anti-apartheid rally by Kansas University police. He is one of the true social justice warrior. Kuby got justice for Darrell Cabey, the victim in Bernhard Goetz’s 1984 New York City Subway shooting. He also won nearly a million dollars for the Hells Angels.

Kuby interned with the iconic radical lawyer William Kunstler, who became a legend defending indefensibly hard cases like the Chicago Seven, the Catonsville Nine, the Black Panther Party, the Weather Underground Organization, the rioters at Attica Prison rioters, and the American Indian Movement. Kuby and worked as an unofficial partner until Kunstler’s death, defending flag-burning protesters, Egyptian-based militant terrorist attacks encouragers, and Malcolm X’s daughter Qubilah Shabazz, when she was accused of putting a hit on Louis Farrakhan of the Nation of Islam.

Kuby testified for Gambino family boss John Gotti’s son, when he was sick of the mobster life. He did this even though Junior Gotti was accused of kidnapping and trying to kill former Guardian Angel Curtis Sliwa, who co-hosted Curtis and Kuby in the Morning on WABC-AM 770 in New York City, with Kuby.

The “Dude” asked for Kuby by name in the 1998 movie The Big Lebowski. The mouthpiece started Doing Time with Ron Kuby on Air America Radio in 2008, and spent some time testifying to Den of Geek about the justice system that dishes it out.

You can watch an exclusive clip from Wrong Man here:

Den of Geek: You’ve been bringing police to court for years, how is it working with them while tackling prosecutorial misconduct?

Ron Kuby: I find it profoundly odd and rewarding. My past relationship with the police is adversarial at best. And this was the first time that I had the opportunity to work with a Detroit homicide detective, and a cold case expert, who used to work with NCIS, and watch as a way they apply their expertise to the same evidence that I’m looking at. And of course, frequently we saw things, no big surprise, in remarkably different ways. And one of the ways this show was structured was to make sure that when we receive new evidence, and when discoveries were on earth, we all kind of experienced it in real time at the same time. So that the discussions, and the disputes, and the questions, and the arguments were genuine, they were spontaneous, and they were a product of our collective existence. I still think the cops spend too much time thinking like cops.

Let me just flip that around. What do you wish more defense attorneys would do? What do you think that they lack that you wish they would do more of?

Defense attorneys lack resources, more than any other single thing. We are, almost all of us, overworked, underpaid, under-resourced, and as a result we can’t devote the kind of attention, energy and thought that we were able to devote to each of these three cases. I mean, we were hired, in essence, as television consultants. But, the amount of time that we ended up spending on the individual cases was in excess of that that usually gets spent by the real people that are really defending and prosecuting these cases.

The other thing the Defense Bar desperately needs is some sort of database of police and prosecutorial misconduct. You would think that in 2018, when there’s a finding of police misconduct, the police planted evidence, the police lied about a search. You’d think that immediately that would go into some publicly accessible database. You’d think that, and you would be wrong. It would be tremendously useful, both locally and nationally, if some such database existed. So, we would be able to look it up say “oh, this is now the 15th person who confessed in this way to this detective.” But for a variety of institutional reasons, no such database exists. And of course, the defense is chronically underfunded unless you happen to be OJ Simpson or Harvey Weinstein.

As far as picking up information for a documentary, you have a lot more at your fingertips than you do as a trial lawyer, don’t you? How is the long-form journalism going to affect these trials, and is that sort of like a database that’s now growing?

Well, the long-form journalism that accompanied our reinvestigation of each of these three cases is remarkably helpful, I think, to the individual defendants. And it’s remarkably helpful in illustrating to the broader public the way police bias, prosecutorial tunnel vision, and the like exist to substantially affect outcomes. I don’t know that it creates any sort of systemic reform, because each of these cases is highly individualized, like the very, very popular serial that started this, Making of a Murderer.

I like to call our work “unmaking of a murderer?” because we’re going back and in essence excavating the case, following leads that were not followed, and re-following leads that were followed originally. But about which we have questions about the outcome. So, I think what it does on a broader level is it shows people how the system actually works, or worked in retrospective. It shows people the work that we actually do, those of us that are working on wrongful conviction cases. And it shows why we should all have a great deal of doubt about the results that we see at the end of the criminal justice process.

Before we get into specifics, what kind of justice comes out of the documentary that won’t come out in court? I know you hired lawyers, or you found lawyers, to work for these people afterwards, but the actual documentary itself is doing what for justice?

Well, we will actually have to wait and see, now won’t we? I mean I don’t mean that in a flip way. But, if the question is “what does this, these films, do for the justice system,” we kind of have to wait until they land. Certainly they have done, I think, substantial good for the three people who are involved in these three homicides. But, the longer effects remain to be seen.

I think it is going to be a growing contribution to a growing body, a multi-platform body of information that holds the criminal justice system to a level of scrutiny that it is not accustomed to bearing. And the fact that it comes not just from the usual suspects like me and other criminal defense lawyers, but it comes from federal investigators, it comes from cops, it comes from people who have a variety of experiences in the criminal justice system who have serious questions about the way these cases were put together and have engaged in some serious work to try to, if not pull them apart, at least separate them out into their component pieces and analyze what is left.

Looking to the Curtis Flowers case, is there a different judicial experience for black and white America, and what is different?

Pretty much every part of the criminal justice system is different for most black people than it is for most white people. And again, there’s always an outlier, there’s always somebody, some white guy out there says “you know what, my cousin Ralph, he got…” Okay. With all due respect for your cousin Ralph, that’s not the typical way the criminal justice system deals with white people. As a general matter, African Americans are over policed, over criminalized, over prosecuted, over sentenced, and suffer from a real lack of alternatives to the incarceration or the punitive justice system.

White people – and here I’m primarily talking about relatively minor offenses, most commonly drug and theft offenses, alcohol related offenses – by contrast tend to be offered a variety of diversion programs, various medical programs, psychological treatment, second or third chances. Because, after all “they have a bright future ahead of them.” And so, why should a criminal justice system destroy that bright future? Whereas it’s presumed for the most part that African American youth don’t have a bright future ahead of them. So we might as well get started on them now.

The Curtis Flowers case, of course, involves this horrific, multiple homicide. And I think probably the most singular part of the case for all people who have been involved in it, is the consistent exclusion of African Americans on the various juries, and the consistent prosecutorial misconduct by the same prosecutor, and a consistent unwillingness of the state of Mississippi to step in and remove that prosecutor.

In the battle of the worlds between one side, Black Lives Matter, and on the other side, the political climate behind our current the President and Brexit, how are they honing justice, the two opposing points that are coming to a head at this point in history?

It’s interesting that there’s not that much of a contradiction between the two at this point. In Trump world, there’s not much of a focus on the criminal justice system, as a criminal justice system. Most of the focus has been a series of horrific attacks on immigrants, and attempts to criminalize immigrants. But there hasn’t been much attention to criminal justice reform on the part of the Trump administration, or reacting to the reforms of the past 50, 100, 200 years. That really hasn’t been much of where the administration is focused. Federal law enforcement for the most part has a fairly limited role in the criminal justice world. That is to say with the overwhelming number of crimes that were allegedly committed in the United States are prosecuted by local district attorneys either appointed, more often elected, sometimes accountable to state attorney generals, but you don’t have an overall federalizing of the American criminal justice system. So they have a limited role, the Trump administration, has a limited role to begin with, and they’re not doing much with their limited role, which is great! Which is just great, please focus on Robert Mueller, or something. Just leave my clients alone.

At the same time, Black Lives Matters, and so many other reform groups, the Innocence Project and others have created a climate where people, regardless of their politics, are coming to a general realization. One, that incarceration is a really bad way to make society safer, or to achieve whatever social goals you want. It destroys lives, it destroys families, and for conservatives, it’s outrageously expensive. I mean to keep somebody in Rikers Island in New York City is $160,000 a year. That’s a four year college program at a reasonably good school wasted every year by incarcerating people. So there’s an overall movement on both the left and the right to de-incarcerate.

Second, there’s much more scrutiny about the ways in which the system obtains its criminal convictions, and a great deal of effort on the part of local authorities, local officials, local grassroots movements to try to change some of that. Most notably you see it in the Philadelphia district attorney’s office, where you had a genuine radical get elected, and basically fired everybody and said “we’re starting fresh with our approach to the criminal justice system. We’re gonna be much more selective, much more careful, and we’re gonna be doing our best to follow the Constitution of the United States and protect people’s rights while we’re protecting public safety.”

Regarding the Evaristo Salas case, what happens when it comes out someone like the lead detective, the detective Sergeant Jim Revard, paid an informant?

Well, historically, nothing happens to dirty cops, period. Unless they’re really, really, really dirty. And by that I mean, the classic example is what we had in New York City with the so-called ‘Mafia Cops’, Caracappa and Eppolito, who were actually members of organized crime and carried out hits, murders, on behalf of organized crime.

And then went to Hollywood to sell screenplays about it.

Even the cop who had wanted to abduct women and murder them and shut them into ovens and eat them, even the cannibal cop only lost his cop. So it’s very, very difficult to hold police officers accountable for their misconduct. Much of the reason lies in the fact that the misconduct is not discovered until many, many years later and the Statute of Limitations has expired. Much of it is due to an institutional reluctance of District Attorneys who need the cops every day in their job, that is to say, every District Attorney needs the police force on their side because it’s the cops that go out, make the arrests, collect the evidence and present the evidence to the DA’s office. DAs are extremely reluctant to go after a corrupt, dirty cops, lying cops. And in policing generally there’s an institutional protection for the police from their colleagues which is “alright, well, this wasn’t great but lots of not great things happen, we’re not gonna ruin somebody’s career over that.”

When you add to that that police officers enjoy qualified immunity for civil suits brought against them, as well as most major cities have indemnification agreements with the police. That is, if you violate somebody’s civil rights, the city, the taxpayers, will provide you with a lawyer and pay the judgment. So, when you have a system where you will not face criminal prosecution for what you do, and if you get sued for it somebody else is gonna pick up the bill, it doesn’t provide much deterrence to bad conduct.

I want to move to the Angie Dodge case. She was almost decapitated. It was a horrible, sexually violent crime, as a person who’s then defending someone who’s accused of it, what happens to you as a person? When you’re looking at these things, what changes about how you’re approaching things?

Well, that is kind of personal and I don’t mind answering it but I can only answer it for me, I can’t answer it for defense lawyers generally. The first thing that I do is to recognize that there is a real victim here. This is a real person was horribly sexually assaulted, and murdered, and so, I try to have as much respect for the deceased as I possibly can. In terms of comments I make in court, about her, documents that I make reference to, even reviewing autopsy reports which I’m entitled to, which are terribly private, intimate things. I try to always maintain my respect for the victim because whether or not my client did it, somebody sure as hell did. And this was somebody’s daughter, and sister, or mother, or friend, and I just try to maintain that level of respect.

And in terms of dealing with my client, it’s hard to know who did it and who didn’t do it. And you would think after doing this for 34 years you might think “oh wow. I have some sort of guilt detector that’s been assembled for more than three decades of practice.” But I don’t. People I think are innocent turn out to be guilty, people I think are guilty turn out to be innocent. So I try very, very hard not to judge the case, and try to review the evidence and see where the evidence takes me with as much of an open mind as I can stomach.

What did you most learn from Kunstler?

Oh gosh. A single lesson I think from Bill in terms of the larger perspectives in life is that almost everything in America comes down to issues of race. That races, and racism, and slavery is America’s original sin, and we’ve never conceived to get past it. Bill always had a tremendous mistrust of state power, period. Even when it seemed as though the state was acting in the interests of the poor and the oppressed, he had a broad enough sense of the sweep of history to know that at best that that interest in the poor, and black people, and the dissidence, and the marginalized, the state interest in promoting their wellbeing at best is transactional. There’s a mutuality of interest around one issue at one point, but there’s no commitment on the part of the state to foster the interests of the masses of people.

And, the most practical level, Bill taught me to never leave a courtroom or judge’s chambers without taking something with you. Pad of paper, pen, stapler. We need office supplies.

I’m the gangster geek at Den of Geek, and I know that you testified for Junior Gotti, and you also did work for individuals who were allegedly affiliated with the Gambino crime family? There’s a documentary coming about Junior Gotti-

Yeah, I know. I’m actually in that and believe it or not-

I saw it last night.

We’re competing. Two Ron Kuby presences competing on Sunday nights at 9 p.m., Eastern time. Little depressing, but cool.

Junior went to his old man to quit the mob, pretty much an unprecedented thing. How do you translate that to criminal defense? All of these people had wonderful defense, so how do you see that as being different to him wanting to get out? I know that it caused problems between you and Sliwa, and I’m a New Yorker so, I’m very interested.

Yeah, well the story, obviously the story behind that story is a very, very long story but I’ll try to keep it mini-segment length. When John Gotti, the younger Gotti, indicted in the mid-90’s there were like 40 people indicted with him in this massive conspiracy. Most of which involved shaking down a topless club for money, so every coked-up business guy who went to a jiggle joint had a pay a dollar extra mob fee. It did not strike me as the crime of the century. But as with so many of these Federal prosecutions, they carry a lot of time. So I picked up one client who contacted me, his mob name was Sigmund the Sea Monster.

Okay.

Right? And actually that becomes a subject of tremendous controversy because John Gotti, the elder, who was in prison at the time was overheard cursing out his son about giving these crummy sounding mob names to people, like “it’s a disgrace, Sigmund the Sea Monster, what the fucking kind of name is that?” Anyway, I was represented Sigmund the Sea Monster when John Gotti approached me with sort of a novel approach which was, “why don’t we all just plead guilty as part of a global plea. Nobody rats on anybody, but everybody takes a plea, everybody gets some time, the government doesn’t have to have a year-long trial.” And I was the one sort of selected to advance that to the government.

Really because no one had done this before and there was not a really good sense that organized crime at large was gonna support this approach, or whether they were gonna view this as a form of snitching. So if in case this thing blew up in everybody’s faces, I could take responsibility for it, say “it was mostly my idea, I thought I could give it a try. I’m sorry if everybody got bent out of shape, so you all just go ahead and go to trial and spend the rest of your life in prison.”

And while the global settlement that I tried to broker ultimately did blow up, it was put back together later on. And John made it very clear, as did pretty much everybody else the case, they did not want this. John in particular, he had a young family, he had a really good life, and he did not want to be part of organized crime anymore. He watched where everybody went, they all went to prison, or died, or went to prison and died, or died but didn’t go to prison. It’s not the kind of job where you get to die in your bed. So, that was one of the parts of his withdrawal from organized crime.

Wrong Man airs on Sundays at 9 p.m. on STARZ.

Culture Editor Tony Sokol cut his teeth on the wire services and also wrote and produced New York City’s Vampyr Theatre and the rock opera AssassiNation: We Killed JFK. Read more of his work here or find him on Twitter @tsokol.