Ram V Is Changing the Face of Comics with Laila Starr, Grafity’s Wall, and Batman

Exclusive: The incredibly talented Ram V tells us how he makes comics informed by his Indian upbringing.

Comics is a realm of the new. It is an ever-changing landscape of fantastic possibilities and new voices. Ram V is among the new wave of brilliant creators changing the face of comics right now, presenting wholly fresh stories that display the medium’s power. Hailing from Mumbai, Ram has roamed the world working as a chemical engineer and now resides in London, wherein he writes spellbinding stories about life in India like Grafity’s Wall, but also grand superhero epics for DC and Marvel. His latest indie hit and Eisner-nominated comic, The Many Deaths of Laila Starr, is among his best.

When did Laila Starr really start forming in your mind?

I think I had come up with various versions of that story long before I even started writing comics, to be honest. There were early versions of short stories where it was “Krishna comes down to Earth!” and whatnot, but I suppose it really turned into Laila Starr when I had this kind of need to write about death, even as a teenager. And I always felt I couldn’t because I hadn’t experienced enough of it, if you will. There are always things you feel that way about, and you feel you’re not equipped to write them, and then BOOM! Studios editor Eric Harburn came to me and said, “You know you’ve done Grafity’s Wall. We want something similar to that, but we want a bit more of a fantastical genre aspect to it.”

I went away and started thinking about stories that could be slice of life, could be about growing up in India, in Mumbai, but also had a little bit of a fantastical element. And literally, both those pieces I mentioned earlier kinda fell into place. And I said, “Okay, I feel like I’m grown up enough to write about death now.” Obviously, the immediate question when you start thinking about writing about death in comics is, “Y’know, what can I say that Neil Gaiman hasn’t said already?” Immediately my head went to this idea that Death is a cultural manifestation. She or it cannot be the same thing necessarily to different people. It is always gonna be a different concept, depending on where you come from, what you’ve encountered in life. So I felt like there were enough new things to say there and yet have it feel poignant and emotive in a similar way.

I remember issue 4, the issue with the Chinese immigrant in Mumbai, where did that come from for you? I don’t think that’s taught to a lot of people in history, I don’t think a lot of people are aware of it, but it’s super fascinating. So where did that come from, when did you know you had to put that in?

If you look at all the issues, they’re looking at the idea of Death in different contexts, right? Like issue 2 with Bardhan in it is the death of someone you perceive is from a completely different world as compared to you. With Issue 4, which is the one with the Chinese Temple, that one is a death of a certain type of city. In that, I’m commenting on how a lot of Indian society has changed over time.

When I was growing up in Mumbai, I had friends of different religions and there was never any fear of people coming over to my place, or y’know, I’ve been over to friends’ place for Eid, I’ve been over to friends’ place for Christmas, and there was never any kind of discomfort or a second thought given to it. But I feel like now that has become unnecessarily laden with too much of this kind of need to express your differences that didn’t quite exist in the city that I grew up. And it made me think, and I wanted to find a way of expressing how a city longs for its own past and dies in some ways.

I didn’t want to do the obvious thing, because I’d already done it in issue 3 where I talked about the Riots in Bombay. So I wanted to look at a thing that no one would possibly know or think of in the context of the death of a place. And so I had known of this Chinese Temple existing in Mumbai, and I’d always found it to be melancholy and romantic, and it just seemed like the right thing to pick up and talk about.

Your books Black Mumba, Grafity’s Wall, and Laila Starr form a sort of Mumbai Trilogy. How has your relationship with Mumbai evolved and changed with time? How do you deal with that in your comics?

I think I read somewhere, and I found this to be quite useful, that a writer’s job was to take something familiar and make it interesting and unfamiliar all over again. Which I think is a very interesting way to look at it, because I grew up in Mumbai, I was there until I was 18–19. And I later went back and lived there for about another three or four years. There are so many things you take for granted, because they’re familiar to you. And then you go and live elsewhere and all of those things you took for granted are entirely foreign concepts in other cities.

One of my earliest experiences of that was to do with friendships, which I think I explore a little bit with Jay and Suresh in Grafity’s Wall. I had friends like that when I was growing up. I could go over to their home and take whatever food was on offer without saying thank you and spend the whole day on their couch even though they hadn’t invited me, and I also had friends who came over to my place and took the keys to my motorcycle and used it all day without asking me or anyone else, and it was completely fine.

Then I went and lived in the States, and you have to knock before you enter someone’s room, even if they’re your roommate. And I completely understand why, but those are cultural markers, they say a lot about the society we grow up in. Even though people keep talking about India and Mumbai as a city of poor people and poverty, there is simultaneously such generosity present.

All these things that coexist with all these other things?

Yeah. Yeah. There are contradictions that defy any kind of stereotyping, really. And so, now, when I go back to the city, I look at all of those things with necessarily fascinated, amused eyes. Which I wouldn’t have been able to do if I hadn’t lived outside. And also I probably wouldn’t be interested in doing as much if I wasn’t a writer.

Given music is so central to much of your work, what do you think about the comics-as-music school of thought?

I think that comics is a very interesting medium in that it finds itself at a crossroads with a lot of other mediums. Architecture in comics is interesting, design in comics is interesting, prose in comics is interesting. And I feel like the one that gets looked at the least in all of that, actually, is music in comics. There’s a very obvious commonality between the two of them in that they’re both heavily dependent upon rhythm. The way you pace a page is very similar to the way you think about pacing a song in music. Again, you’ve got three or four different people playing, like a band. But also, how much each person does in the same unit of time is very important to how good your song sounds, and the same is true in comics. There has to be a balance of how much each person does in each given real estate on the page. And that’s on the technical aspect of it.

On a more creative aspect, I think good storytelling always pushes to create some form of synaesthesia. In that, you start blurring the lines between “Am I reading something? Am I hearing something? Am I touching something?” Good prose does that as well, so there’s no reason good comics shouldn’t. And uniquely, because of this technical relationship with music, there’s a possibility of making people hear things in comics, which is unusual, and so I like using that. So I think that ties in really well with my love of music.

You’re launching a Detective Comics run in July. What are your Batman touchstones, whether they be creators, texts, or movies?

I’m gonna leave out the obvious ones in that, y’know, Year One is great, probably one of the best comics ever made, period. But Batman: The Animated Series is a big touchstone, although it is outside comics. I think within comics, a lot of the Tim Sale Batman work with [Jeph] Loeb. Certainly, it’s a big influence for me in the stories that I’ve enjoyed. And then there have been bits and pieces of runs that I’ve really enjoyed. The [Grant] Morrison run certainly is a big influence. There are definitely beats and characters taken straight out of it that I’m using in the current run. There are bits and pieces of [Scott] Snyder’s Court Of Owls that were certainly things that I enjoyed. And then there are also things that aren’t considered mainline Batman books. Gotham Central is an influence. Black Mirror by Snyder/Jock is a big influence, bits and pieces of the [Tom] King run, so I’m taking bits and pieces from everywhere.

How do you deal with the intense and massive fandom that comes with handling these global icons?

It makes no difference to me, I’m very good at ignoring the fandom part of it. Not that I condone ignoring readerships or anything of the sort. But necessarily I think, and I’ve had this discussion before with people who’ve taken umbrage to it, because fanfiction is a thing, and I’m not speaking against fanfiction when I say this: if you’re hired to write a character, you cannot approach it as a fan. Because you have to be willing to do things with those characters that push them into places they haven’t been before. And necessarily, the definition of a fan is someone who thinks what they’ve already read or consumed is the best version of that character, that’s why you’re a fan.

But your job as a creator is to go: “What can I do that hasn’t been done before? What can I do that is new? What can I do that will create new fans rather than satisfy existing ones?” And because there is that sort of intrinsic conflict between those two approaches, I don’t consider myself a fan when I am writing. But also, my interest in whatever I’m working on ends when I’ve finished writing it. And when I say writing, I mean finished creating it, in that it’s done, it’s a finished PDF, and it’s lettered and it’s off my desk. The moment that is done, my attachment as a creator has ended. So I almost have no reaction to how people feel about it after that.

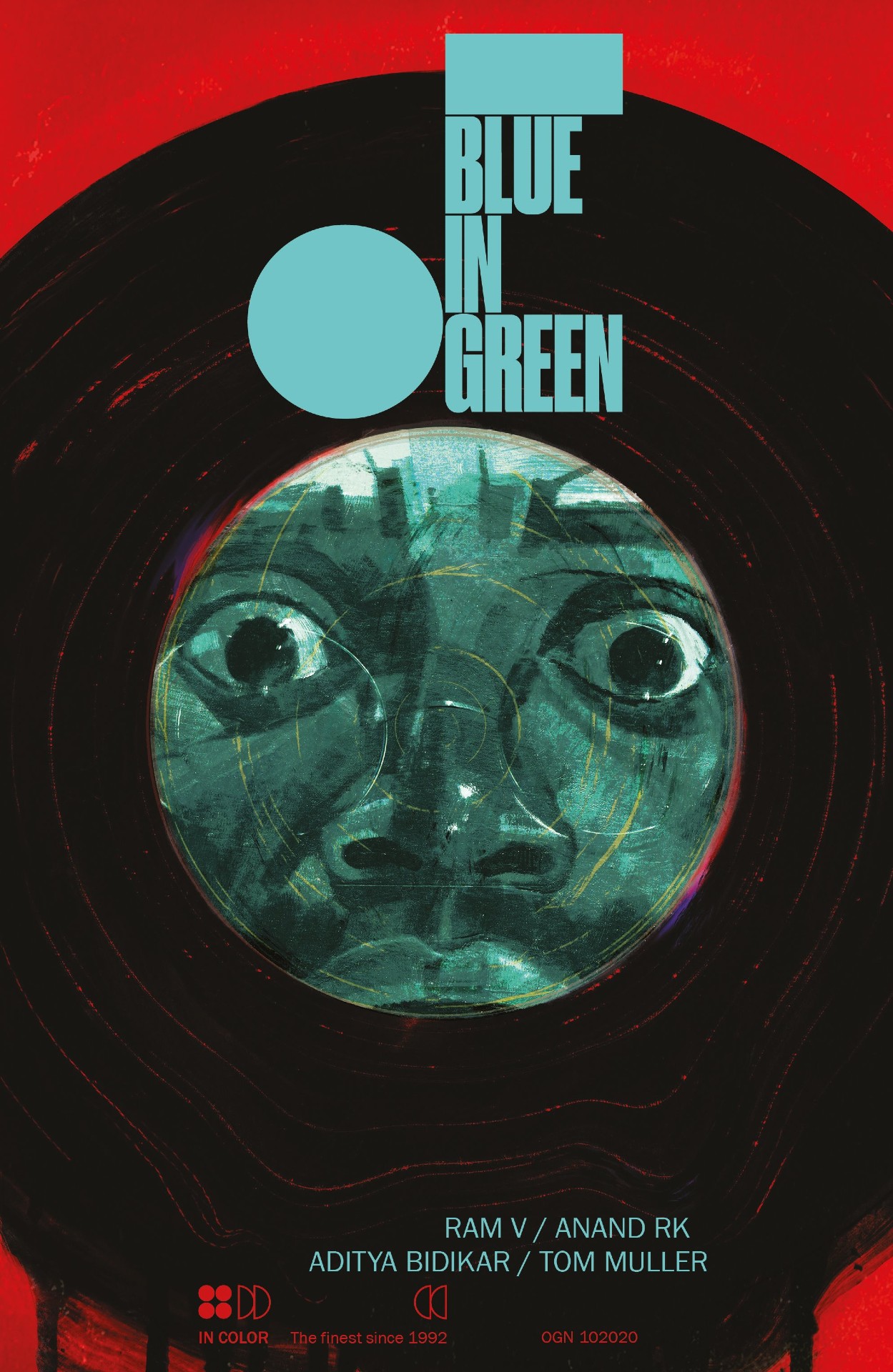

It seems like an odd thing to say, but it’s also true of my creator-owned work. I remember there was this time I was talking to my collaborator Aditya [Bidikar] who had re-read Blue In Green, our musical noir OGN, just as it was coming out and he’d messaged me to say “Hey! I just read the whole thing! It felt so good! We really made something cool!” and I appreciated that, but also I went “Ahh, I don’t wanna look at it! I can’t stand looking at it one more time!” I have to develop a disconnect with a project before I can come back and look at it with any kind of objectivity.

I feel the same way about the work I do on these big characters as well. I do get a lot of fandom reactions. Most of the time, they’re really nice, in that people have really enjoyed the work. Sometimes they are a bit negative because someone expected something and they didn’t get that. But largely all of that is like, “Huh, cool,” and then it’s done.

That’s a very healthy way to approach it.

Yeah. I’ve never been interested in finding engagement or validation through that side of things.

The Many Deaths Of Laila Starr is out now. Detective Comics #1062 drops on July 26.