How We Use Dystopian Landscapes to Tell Very Human Stories

From Mad Max to Children of Men, Caroline Hardaker, debut author of Composite Creatures, writes about pop culture's use of dystopian landscapes.

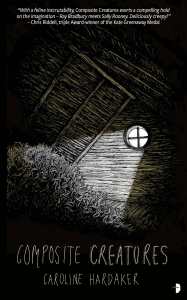

This guest post was written by Caroline Hardaker, author of Composite Creatures, a character-driven science fiction debut about the burgeoning relationship between two people set in a melancholic and mundane near-future climate change dystopia.

When we think, we escape our biological bodies. We hardly ever reflect on it, but from the day we’re born until we collapse into ash – that’s all we are. Organic machines, birthed in balance with an environment we spend our lives harvesting. No matter how much we sometimes take it for granted, we can’t survive without the land, sea, and sky working in perfect harmony, yet we all likely face a problematic future where the world will look quite different.

Writers and filmmakers are obsessed with imagining this speculative future. And not only how it’ll look, smell, or feel, but also how humans will engage with it emotionally. If the earth transforms into a different planet, will we transform into different people too? Modern books and films depict the future of environmentalism in a whole host of ways, from burned-out deserts to boots burning upon a toxic wasteland. In each, often it’s how humanity engages with nature which is the most interesting aspect of the storytelling. Yes, there are aesthetic changes to the sky, sea, and soil, but often it’s humans who’ve changed the most.

It’s something I wanted to explore on a domestic level in my novel, Composite Creatures. Set in a very near future, many of the changes are subtle – creating an uncanny eeriness that it’s hard to shake off. A lilac-tinged sky, a metallic taste on the air, and mice that scurry up trees just slowly enough for you to spot the stitches holding their limbs together.

But, sometimes, dystopian landscapes are revealed as alien worlds, almost unrecognisable to our own…

Perhaps the landscape that first comes to mind when imagining a typical, desolate future is the sort of barren sandy stretches in 2015’s Mad Max: Fury Road—an environment in which humankind has reverted to a mechanical way of life in order to survive the heat and brutal stretches of ‘nothingness’. Survivors continue only by embracing sex, drugs, racing, fighting and looting. Every minute in this world is a struggle, a fight against the elements. Sand clings to skin, blinds the eyes, and rattles in the lungs. The sun mercilessly burns everything beneath it, and the characters can only watch as the planet disintegrates and blisters into a dead, dusty flatland.

The dead landscape and emotional ‘nothingness’ are taken to the extreme in Cormac McCarthy’s Pulitzer Prize winning novel, The Road. A story about a father and son travelling across a cold, dead landscape stripped of all colour and life, this haunting, post nuclear landscape is frequently hailed as a terrifyingly realistic depiction of what will happen in the event of environmental collapse. McCarthy never shies away from the future’s bleakness, and frequently making the connection between a dead world and a dead emotional state. Survivors live as scavengers and cannibals, their humanity burning away with each day. Even the father and son kill to survive, prompting the son to ask his father if they’re still the good guys. When it’s kill or be killed, where does this leave morality?

Set in England in 2027, P.D. James’ Children of Men has become another classic depiction of environmental apocalypse. Here, an unknown catastrophe has rendered humanity infertile. The planet is in a state of collapse and the youngest person on Earth, we are told from TV reports, has just died at the age of 18. Britain exists as an authoritarian state, attracting migrants fleeing plagues and nuclear devastation. But they arrive to find a hostile environment of xenophobia and societal paranoia. London is a grim landscape of terrorist bombings and security checkpoints; of prowling military, sealed-off spaces, grey buildings, barbed wire, filthy streets, and armed police. Life is cruel, and humanity has turned away from nature and into itself. Individuals keep their heads down and look out for themselves, stumbling around their neighbourhoods as if drunk on life’s bitterness. Unlike Mad Max, there are no technopunk gadgets to help communities surf this new landscape. War, isolation, and a lack of hope has sapped any energy and left humanity in a fog of its own misery. The only thing holding society together is the desperate desire to pretend everything is normal; to continue, to keep breathing, to keep calm and carry on.

This ‘turning a blind eye’ is also seen in Margaret Atwood’s Oryx and Crake, which explores the consequences of biotechnology on nature and society. Atwood describes a world where humans are the cause of environmental destruction, and even in the realisation of this they don’t stop. In fact, they continue to develop new ways to manipulate the natural course of the world. In Oryx and Crake, scientific corporations with the scientific know-how to genetically alter animals run the world, and nothing is quite as it seems. All ‘natural’ aspects of the planet’s biology are now extinct, and the environment has become the petri dish for one long experiment. Here, humanity doesn’t learn from its mistakes.

Regardless of how the environment arrived at its ruin, these dystopian landscapes frequently become the main antagonist. It doesn’t matter if we’re to blame for polluting the soil or for melting the ice caps – humans frequently battle these new wildernesses to survive. Picture the endless, dangerous seas in 1995’s Waterworld, for instance. Kevin Costner embodies the only character we see whose body has adapted to the environment, and this causes him to be ostracised. Does having gills and webbed digits ally him with the enemy water, perhaps?

Similarly, in The Girl with All The Gifts by Mike Carey, it’s the moment when Melanie partners with nature to deliver an ending she believes will provide the young with a future when we (as the reader) are left questioning the morality and finality of her actions. Poor Miss Justineau, the only remaining central character to which we can relate, must live in a bubble, forever disconnected from the air.

These aren’t the only worlds that condemn those who are more engaged with the environment. In Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, those who do not have a use or place in Gilead are sent to the outposts, to spend the rest of their shortened lives cleaning up toxic waste. Those in power have split Gilead into two halves – a heaven and a hell – a religious utopia balanced by a polluted, poisonous nuclear netherworld. Unlike many other dystopian landscapes, here those in power have deliberately done everything they can to shape a heaven from a broken, polluted America, in which fertility rates are dropping and religious radicalism is on the rise. They brainwash citizens into believing that Gilead is exactly the new land that God would want, shining up their constructed utopia to hide the reality of the man-made nuclear wastelands their new world is built upon.

Dystopian futures routinely feature landscapes shaped by mankind’s poor decision-making. Mankind’s blame for environmental deterioration is often only a little mentioned fact aside from the main plot. In 1999’s The Matrix, we’re shown a jagged horizon lit by an angry storm as Morpheus explains to Neo that humans deliberately scorched the sky to strike a blow to the solar-powered machines. Ironically, this decision meant that the earth’s surface became uninhabitable, and in a cruel twist of fate, human bodies become organic batteries, photosynthesising energy to fuel the machines we created. And just like with Gilead, the remaining humans create a new ‘heaven’ under the earth’s crust – Zion – to escape the horrors of the world they’ve poisoned.

Perhaps it’s not so ironic that – regardless of the particulars of the dystopian world – in depictions of futuristic environments, it is humans who regress. As the world moves forward, we devolve and take on animalistic or primitive behaviours. We become batteries, scavengers, cannibals. Even when the horizon is dark, and the stretches of ‘nothingness’ reach on as far as the eye can see, we adapt with a kind of stubborn resilience. We build new technologies to survive however we can, and build emotional walls to stop the terrible truth from sinking in.

Composite Creatures is out today, and is available to purchase wherever books are sold. You can find out more about Caroline Hardaker and her work here.

In celebration of Composite Creatures’ launch, Angry Robots is hosted a free digital launch party at 7pm GMT/2pm ET.