Pixar, Coco, and the Importance of Memories

We take a detailed look at Pixar's Coco, and at how Pixar's movies deal with memory...

This feature contains major spoilers for Coco, and spoilery discussion of several other Disney and Pixar films, with spoilers for Frozen, Big Hero 6, Up and Zootopia.

All films are about memory in one way or another. The way we engage with and absorb media is always going to depend on what we’ve learned and retained about the world during our lives, whether it reflects our own experiences or other things we’ve consumed. But we can’t think of another studio that engages with memory as a concept as Pixar does in their feature films.

From forgetful characters to the literal objectification of memories as a plot device, memory is a key tenet of many of Pixar’s 19 features to date, even in films where it’s not at the forefront. Bob Parr is nostalgic for his superhero days in The Incredibles, WALL-E‘s fakeout ‘Disney death’ comes when his internal memory and personality are briefly reset, and the emotional wallop of Toy Story 3 relies as much on the time we’ve spent watching the toy characters in the previous films as on the characters’ own memories.

Pixar’s latest film Coco is unmistakably one of the major films in this trend, presenting a portrayal of life after death which is directly inspired by the Mexican tradition of Dia de los Muertos, but also grounded in the studio’s previous representations of memory in their stories. It’s only natural then, that Coco‘s treatment of the subject reminds us of previous films too.

Lost memories

In Coco, the title character is actually the elderly great-grandmother of our protagonist, a 12-year-old boy called Miguel Rivera. Miguel’s family are shoemakers who have a particular aversion to music, because Coco’s father was a musician who abandoned his family when he was very young. His picture has been removed from the ofrenda, the altar where the Rivera family keep pictures of their late relatives along with offerings for the Day of the Dead.

Miguel comes to believe that his great-great-grandfather was actually the Elvis Presley-esque Ernesto de la Cruz, his personal hero who grew up in the same hometown, and takes this as confirmation of his destiny as a musician. But when he steals Ernesto’s guitar from his mausoleum, he becomes cursed and is transported to the Land of the Dead until he receives his late family’s blessing to return to the living.

That’s the basic plot, but there’s a reason why the film isn’t called Miguel. We learn early on that the title character is afflicted by dementia, and she represents the real emotional stakes of the film. Science has shown that music stays with people who have the illness longer than other memories, and by the absence of music in the house where she lives, she has forgotten her father.

Over in the Land of the Dead, we’re told that the skeletal souls that go on after they pass away can fade away forever if nobody alive remembers them in the Land of the Living. Miguel tries to make his way to Ernesto to get his blessing with the help of Hector, a scruffy chancer who is also on the verge of being forgotten, in order to save his own life and restore his great-great grandfather on the ofrenda.

It’s one of Ernesto’s songs, the Oscar-nominated Remember Me, that gets through to the ailing Coco, because it was composed as a lullaby specifically so that she’d remember her dad when he was away on the road. At the climax of the film, she finally hears the song once again and he finally comes back to her before she passes away. Shut up, I’m not crying, you’re crying.

The sensitive treatment of memory loss here varies from the comedic portrayal of Dory’s short-term memory loss in Finding Nemo. The studio already made some headway in that respect with the sequel, Finding Dory, which parlayed the literal missing fish case of the first film into a more figurative self-discovery, as Dory struggles to reunite with her parents. While Dory is a brilliant comic creation, the sequel put up a far more sensitive and thoughtful portrayal, and Coco similarly takes the character’s unreliable memory seriously.

The memory cheats

Of course, it’s not only an unreliable memory that complicates Coco. Ernesto is loved by legions of fans in both realms, so there’s no danger of him being forgotten forever. But then he’s not Coco’s father, but the man who murdered Coco’s father. Hector, his bandmate, is not only Miguel’s real ancestor, but also the writer behind all of Ernesto’s songs.

This falls in line with several recent Disney films, as the studio has subverted its own formula and tropes across its animated films. In Frozen, the handsome suitor Prince Hans is a power-hungry lunatic who plans to bump off one or both of Anna and Elsa to seize the throne. In Big Hero 6, the supervillain is the avuncular college professor rather than the dodgy industrialist. And in Zootopia, the lead conspirator who stirs inter-species conflict for her own gain is the flag-waving progressive, rather than the police or the government.

A lot of recent films have been remarkable for their lack of a traditional antagonist compared to previous classics, but when one does emerge, they often turn out to be someone that the protagonist admires, and so it goes in Coco, where the beloved musical idol is actually a murderous plagiarist, while Hector is falsely remembered as a selfish deadbeat dad. If it was intentional, it’s a canny bit of foreshadowing that Ernesto’s a total bell-end, when we learn how he met his own end when he was crushed by a giant bell.

Elsewhere in Pixar’s filmography, we find characters who are bound up in memories that don’t quite match up with the reality. Every Buzz Lightyear comes fresh out of his packaging with the pre-loaded delusion that he is a member of Star Command, engaged in battle with Emperor Zurg. Memory informs our view of the world, and although it’s often painful for a character to be disabused of such notions, they learn and grow.

Most notably, Up has Carl Frederiksen take his house and all of the possessions he shared with his late wife Ellie to South America. At his lowest ebb, after falling afoul of the adventurer who inspired them, Carl turns to his book of memories.

Only by looking more closely does he find a message from Ellie telling him to make adventures of his own, and only then does he let go of their possessions, and the house in which they lived, because as in Coco, those we love live in our memories rather than in the material world.

Happy memories

Outside of Coco, the other major memory movie from Pixar is Inside Out, which anthropomorphises the emotions of 12 year old Riley, a la The Numbskulls, to tell an internalized story of existential crisis spurred by a move from Minnesota to San Francisco.

Inside the film’s mental infrastructure, Riley’s mind is powered by core memories, represented by brightly coloured balls that constitute her personality and outlook. They’re all happy memories of Minnesota, which is why Joy is the head honcho, but while she sees Riley’s encroaching Sadness as a disaster, the film’s approach is about acceptance and growth. Happy memories can become sad ones when you miss them – Sadness is as much a part of life as Joy, Fear, Anger or, um… Disgust (we’re still not sure about that being one of the five biggies.)

As a family friendly movie, Inside Out relies upon a narrative-friendly simplification of an ambitious psychological disaster movie premise, but it stands as one of the studio’s very best movie thanks to that empathetic core. Similarly, Coco tackles the afterlife, and those who are left behind, by focusing on the happy memories, even when they turn bittersweet.

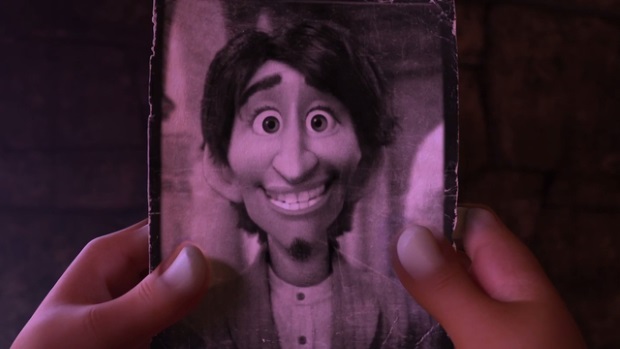

The film’s McGuffin is a photograph of Hector that he wants Miguel to take back to the Land of the Living before he even knows they’re related. As the film has it, placing a photo of someone on the ofrenda allows that person’s spirit to visit the Land of the Living during the Day of the Dead celebrations, like a passport, complete with customs officials checking that the spirits can pass.

But in Disney’s own terms, the photograph is Dumbo’s feather. It’s the memory of Hector that keeps him from fading away. From the ideas presented to the theme song, Coco is another Pixar film that prizes memories and what they teach us about the world.

It would be easy to be cynical about the commodification of memory by Disney, a company that still subsists to some extent on consumers’ good memories of its extensive legacy catalogue. But the films speak for themselves. The key to Pixar’s emotionally ambitious storytelling lies in the memories it makes, both for their characters and for their audience.