The Simpsons Season 31 Episode 20 Review: Warrin’ Priests (Part Two)

The Simpsons adds a new testament to old testimony as “Warrin’ Priests (Part Two)” testifies to longer stories.

This The Simpsons review contains spoilers.

The Simpsons Season 31 Episode 20

The Simpsons season 31, episode 20, “Warrin’ Priests (Part Two),” concludes the epic story of Timothy Lovejoy, Jr.’s mythic battle for the reclamation of The First Church of Springfield. The winner is the audience because the story ran well in a two-part arc.

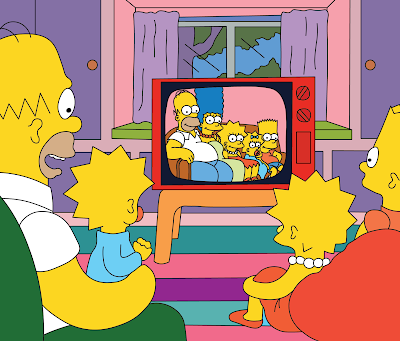

It’s rare The Simpsons turns in hour-long stories. The couch gag opening references the only other two-parter previously broadcast for the show where we learned who shot Mr. Burns. Brockman is the tie-in, for anyone who might have missed the first episode. While he narrates, the crawl taunts anyone for missing the first, which is a wonderful example of Simpsonian subtlety. We are knocked over the head by the most obvious gag but it’s hidden off to the side. Jimbo also scores a memorable sight gag as he takes keys for valet parking for the newly crowded church and joy rides them straight to hell. Fat Tony pays homage to The Godfather, saying this is the first time he’s been in church when he wasn’t establishing an alibi for a montage of mob violence. He is in the church, and we all see him, if every called in for questioning later. But he is there to bear witness, not to slay one.

Lisa is the most prominent Simpson during the episode, much like she was when Todd Flanders was filled with doubt. Lisa is so happy she may have found a faith, it moves her to song. Because when she hears the new preacher sermonize, with those hazel eyes, everything comes together. “I’ve got Buddha, I’ve got science and now Jesus makes three,” she sings. This may be the first time she’s had fun on Sunday, and it’s as miraculous as seeing the face of Moe the bartender on a burnt toast. Homer, meanwhile is happy to learn he shares a special love with his daughter, sleeping in church.

Lisa gets the opening song but Mr. Burns has the original scriptures, encased in glass. He’s always been more of a devilish aficionado, admiring the cut of Satan’s jib, and obviously hasn’t been keeping up with the newest of testaments. “Blessed are the poor,” he learns and immediately goes into cover-up mode, shredding the evidence before the Roman Catholic Church gets a hold of it.

The new preacher, Bode, believes religion started as a way to connect people, and he wants to reconnect it, like a broken ligament. This moves Dr. Hubbard in a spiritual way, and Dr. Nick educationally. He didn’t know ligaments could be reconnected. “Malpractice makes malperfect,” he says, as he promises to retain this epiphany, but we know he’ll forget before his next scheduled surgery. Everyone in Springfield gets something from the new preacher because it is a group mind kind of town.

There is one bee in the Sunday bonnet of the hive mind, immune to the honey pouring out of the mouth of the narcissistic kumbayoyo on the pulpit. The New Evangelical Deacon, who we know by his acronym, Ned. He is a traditionalist who likes brimstone with his fire and not that fancy name-brand brimstone either. That only leads to the temptation of covet, and Homer’s got enough of that for the whole town. Ned is the person who puts Bibles in hotel rooms, and if it weren’t that he had a rule against it, he would be “Homer Simpsoning” out of church before the minister gave his blessing.

Homer’s confessions are classic, besides coveting his neighbors riding mower, he also admits he never pedals on a bicycle built for two, that he was trick-or-treating until he was 30, and once told Marge he was going for a colonoscopy when he was actually going for Planet of the Apes marathon. He also cops to having impure thoughts about the mother bear the toilet paper ads. When Bode asks whether this Flanders guy ever annoys Homer, it takes not one, but two spit-takes before the Simpson dad calmly replies “from time to time.” Homer also assumes that when he goes to the church’s “Aloha Sunday Meeting,” that this is what it must be like if they “believed in god in Hawaii.”

Reverend Lovejoy is on his mission to reveal the mysterious past of the popular preacher. The Simpsons has fun modernizing the traditional in the modern big-time churches of Michigan. They have educational computerized panels with answers to everything from how to tell a good Samaritan from a bad one, whether it’s OK to be gay and probably even one on how to validate parking during the rapture. We also learn the secret code words to prove ministerial membership: “Church, steeple, doors, people.” That’s something even The Boston Globe hasn’t cracked.

It turns out the pastor has a little dirt on his collar. It’s a short story but one which can go on forever with embellishments. The Simpsons seems to be making a self-referential barb about the doubled length of the story, they needed two episodes to say the same thing they could’ve said in one segment. They are a preacher taking way too long to make a simple point before they get to the proof. In his youth, the reverend burned with idealism and it spread to the pages of the good book.

The Scripture War showdown between Ned and Bode pays homage to Spaghetti Westerns, with each man doing his best Clint Eastwood man-without-a-name-character squint. At the end, the young minister leaves Flanders cold, and he is wearing three sweaters.

Reverend LoveJoy makes a comically dramatic entrance to reclaim his church. He gives Abe Simpson the honor of pointing accusingly at the heretical Bible burner. It’s the right choice. Abe never met a Hittite who wasn’t trying to upend an empire. He remembers another guy, with crazy hair and crazier ideas, who had the mob with him, until they turned, horribly: Willie Nelson. I miss the days when Abe was a cranky old crank writing angry letters with ridiculous demands.

The “impreachment” hearings are so sad, even the fire eaters celebrating the first Sunday of Lent lose their appetites. This is a town which banished a guy for wearing two different colored socks. Their NPR station broadcasts wrestling during pledge week. Springfield “has a way of rejecting what’ new and different and better,” Marge notes earlier in the episode. Lisa’s vision board, which was supposed to hold a lifetime‘s worth of disappointments, breaks under the weight of it.

The town is torn, of course. We learn the Sea Captain is the most woke member of the community. “Activism means nothing if it’s not intersectional, yar,” he imparts. The Simpson family also sides with the banished Bible burner. But tests his own faith. They invite him to dinner but won’t know if he truly believes in a forgiving god until he sees them eat and loves them anyway. Lisa also gets to yell at the priest for not burning something irrelevant, like one of Bill O’Reilly’s books.

“Warrin’ Priests” is a parable. Springfield is America. The majority of people are as desperate for change as they are desperately afraid of it. The episode is a testament to longer-form Simpsons. The series gets more adventurous, allows more attention to details, develops supporting personalities and lets the tensions grow. It almost felt like this episode could’ve used another full segment, but it is Chief Wiggum who gives the entire episode closure. He is the one of the ones desperate for change. He saw something new, as traditionally old-school as he is, and he wanted it. He would be a tragic figure if he weren’t so funny, with a beautiful wife and kid as a punchline albatross.

Chalkboard: I will stop reminding the principal that I have a later bedtime than him.

Keep up with The Simpsons Season 31 news and reviews here.