Normal People Ending Explained

Confused by the ending of Normal People? We break down everything that happens at the end of Hulu's new romantic drama.

One of the many strengths of Normal People—both Sally Rooney’s sophomore novel and the new Hulu adaptation—is how it shows the way that two people can interpret the same events in wildly different ways. While this can be both painful or poetic, it does mean that some of the events can be confusing, or are left open for interpretation. Here’s a rundown of how this atmospheric and all-consuming show ended, how it differed from the original novel, and our view of what it all means.

Rob’s Death

After their childhood friend Rob dies by suicide on New Year’s Eve, Connell goes into something of a tailspin and Marianne comes home from her Erasmus year abroad. She leaves behind Sweden and the strange, abusive relationship with photographer Philip, which started out as consensual (if concerning) but ended decidedly not.

It doesn’t take long for Marianne’s presence and Connell’s reaction to get his girlfriend Helen’s hackles up, and Connell’s immense grief brings to light all the pre-existing problems in their relationship. Helen leaves him, and with his last tether to a semblance of a normal life gone, Connell sinks deeply into a depression until his roommate suggests he reach out to a counselor.

Rob’s death brings Connell’s depression into sharp relief while his guilt over not answering his friend’s last message and drifting apart is an extreme manifestation of the discord Connell feels between his life at Trinity where he’s meant to be a successful writer but is instead painfully aware of his status as a small town working class kid, and life back in Sligo, where he was beloved even if not particularly challenged or understood by anyone other than Marianne.

Marianne and Connell Get Back Together

Marianne goes back to Sweden to finish her studies, and she becomes Connell’s entire support system outside of his counselor and his mother. When her Erasmus year ends and she comes back home to Sligo, Connell spends his weekends coming back to see Marianne, who is once again trapped with her distant, disapproving mother and abusive brother.

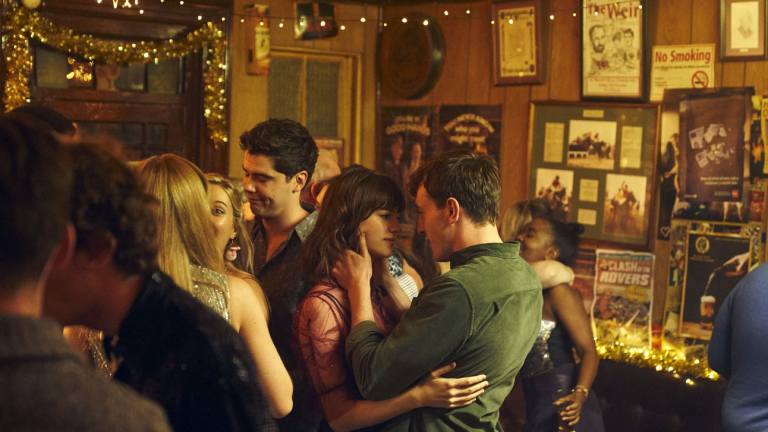

Cue more longing glances and an almost-kiss in a nightclub that turns into Connell striding off into the night—because these two are never quite in sync. On a hot and sticky day while Connell watches soccer, Marianne forces the question of their relationship. Connell is afraid of ruining their friendship since she’s literally his only friend and he’s just getting back on his feet, but they have sex. Which seems to be going well until Marianne tells Connell she belongs to him and asks Connell to hit her, something he knows her previous boyfriend Jamie used to do. Connell tells her he doesn’t think he can do that and—in keeping with his dexterity with consent, if nothing else—he asks if she wants to stop since he won’t.

It’s still unclear if Marianne is just into BDSM or if this is part of her self-worth issues. It’s particularly interesting since she once told Connell their relationship didn’t “need all of that” because of how sexually compatible they were. In any case, she takes Connell declining to hit her and verbal bumbling about it as a rejection of her.

Marianne Leaves Home

After leaving Connell’s due to the sexual misalignment, Marianne’s brother throws a glass at her and breaks her nose with a door. He has long tried to control his sister but is suddenly not a fan of Connell due to the stigma of mental health issues, which he uses as his excuse to confront Marianne about it. She calls Connell for help with the wound. Now aware of the abuse since Italy, Connell comes over to set her brother straight, despite Marianne’s protests. Marianne leaves her family home for good, spending Christmas with Connell’s family instead, and eventually getting an apartment in Dublin with Connell when they’re back together.

Connell Goes to New York

A university in New York offers Connell a place in their MFA program. He applies, thanks to the encouragement of the literary magazine crowd where he was a celebrated editor, ending his school years a success in spite of everything he went through along the way. Connell doesn’t want to go, but Marianne encourages him to. He tries to make her go with him, but she declines.

How the Normal People Ending Differs From The Book

Overall, issues of class are more prevalent throughout the book, and the ending is no different. While we briefly glimpse a numb Connell eating in a Trinity dining area, the unspoken backstory is that all meals are included in the scholarship he won, but only if he eats at the dining hall. Those who can afford to eat elsewhere do, and the place becomes a physical reminder to Connell of both how alone he is and how deeply in need of the scholarship. He oscillates between hunger after eating the meager meals he can financially afford and has the emotional capacity to prepare for himself, like beans on toast, lying in bed all day eating nothing at all, and dragging himself to the dining hall in loneliness and shame, making every meal both a chore and a rebuke.

Marianne’s sexual proclivities have a slightly different treatment in the book as well, where word gets out about the images. The issue of consent is far murkier here, since the book doesn’t depict Marianne straightforwardly asking for a dom/sub relationship or a clear violation of those boundaries, but rather an entire relationship built on the idea that Marianne is punishing herself for not being worthy. There’s little exploration of what, if anything, the photographer thinks about all that, though it’s hinted he was at least somewhat opportunistic about the whole thing. The Sweden trip also happens just a bit earlier in the book, helping set up the tweaked ending.

One major difference is that we don’t know much about Marianne’s life at this point, so it makes her decision to stay in Ireland feel strange, or like a manufactured obstacle to contrive the weepier ending. On the other hand, in the book, Marianne has a career of her own and an entire life that she’s fought hard for, independent of her abusive family and the toxic members of her college friend group. Another is that Sadie, at the literary magazine, is a bigger character, as is Connell’s sex life with other women in general, so the possibility that he might be in love with Sadie or just sleeping with her feels like a real possibility to Marianne, if not the reader, just like Helen once thought about Marianne herself.

While a list of the events that end both the show and the book would probably be nearly identical, the tone is quite different. The same lines of dialogue, such as Connell saying he wouldn’t be here if it weren’t for Marianne, reads completely different in the context on the page, where it feels like Marianne is owning some twisty role in his life that she’s almost ashamed of, versus on the show, where it’s Connell acknowledging the gift of helping him through his depression she gave to him.

The show ends with Marianne sending Connell off onto his great big New York adventure with a wistful, loving mood, trying to be realistic about the fact that their lives are truly diverging for the first time. It imbues the rest of the show with a feeling that it’s a story of the place a formative first love can have in your heart, the way they can change you forever and always be special to you, even if you ultimately part ways.

The book, on the other hand, ties back into the theme of the power imbalance that we saw at the beginning of their journey, with Connell the one who sets the terms and Marianne the one who patiently waits for him to want her and to set the terms for what wanting her looks like. She describes how, “his life opens before him in all directions at once.” Meanwhile, she’s simply grateful that he made her good, saying “the pain of loneliness will be nothing to the pain of what she used to feel, of being unworthy.”

Instead of Marianne saying they shouldn’t wait for one another and ending with, “You go. And I’ll stay. It’ll be ok,” she says, “You should go, I’ll always be here. You know that.”

The effect leaves the reader feeling that, rather than parting on loving terms, these two are forever locked in a codependent dance, never quite capable of getting beyond their own insecurities to see one another clearly, communicate their real feelings and vulnerabilities, and truly be together as equals. But they’re also not capable of letting go—she’ll always be there waiting and wanting to be used by the first person who made her feel seen, and he will always come back to the first relationship that made him feel worthy, regardless of whether it’s any good for either of them.

Normal People is now available in its entirety to watch on Hulu or, if you’re in the UK, the BBC iPlayer.