Doctor Who: What Each Actor Brings to the Role of the Master

Who was the best Master in Doctor Who? Every on-screen actor has brought their own unique qualities to the role (but, short answer: Roger Delgado. Obviously.)

Sometimes you’ve just got to look at the general vibe of 2020 (the furnace bit in Toy Story 3 but half the toys are drinking lighter fluid) and decide to write something positive. On my way to nursery, another dad was telling me how he found Sacha Dhawan’s performance as the Master in Doctor Who a high point of the last series, so inspired by that, let’s celebrate what was good about each actor to play the role on television. If nothing else, it’ll probably be good for my mental health and give someone a chance to type ‘Of course Roger Delgado was the original and best’ in context, so hopefully that’ll make them happy too.

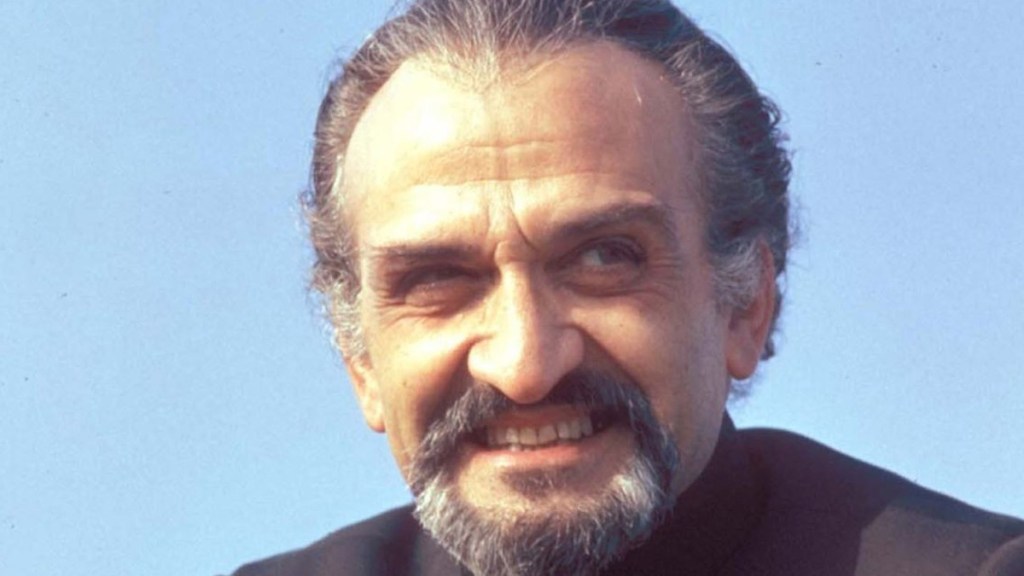

Roger Delgado (or to give him his full name ‘Roger Caesar Marius Bernard de Delgado Torres Castillo Roberto’ – which is Spanish for ‘Of course Roger Delgado was the original and best’) originated the role, playing the character regularly from 1971 until his death in 1973.

‘Terror of the Autons’, his first story, has the Master hypnotically influence people and murder them in a variety of nasty, convoluted ways. The character developed as an inversion of Jon Pertwee’s Third Doctor. Pertwee insisted on a few “moments of charm” sprinkled into the scripts, but his Doctor was also curt, loud, arrogant, and antagonistic. Delgado’s Master, on the other hand, was charming, pleasant and witty.

Delgado’s performance reminds me of a Christopher Nolan film: there’s a sense of confidence, almost elegance present that makes something potentially ridiculous feel contextually sensible. Of course the Master is allying himself with someone who will inevitably betray him; he has a series of incredibly realistic face masks he can generate seemingly at will, and of course he’s decided to pose as a legal official for no obvious reason. This is his great skill: the poise to carry off the ridiculous and terrible as perfectly reasonable.

The Master’s Masks

The character returned in 1976’s ‘The Deadly Assassin’. With Delgado having passed away and writer/Script Editor Robert Holmes planning on leaving Doctor Who, he wrote a Master who could easily be written out by the next production team: a skeletal creature, born of pragmatism, with ambitious plans and nothing to hide his sadism. This Master would destroy Gallifrey and hundreds of other planets to cheat Death, whom he evokes in appearance.

The Master was planned to be the villain in Holmes’ final story, ‘The Talons of Weng-Chieng’, directly placing the character into the territory of Jack the Ripper. This version of the character was accordingly vicious, and what Peter Pratt brings out is bitterness. Working from behind a mask, Pratt’s voice and body language are at their best when the Master is operating from the shadows, the strained whispers of a dying man bent on vengeance. The Relationship is no longer playful, it’s sadistic.

Geoffrey Beevers’s Master in ‘The Keeper of Traken’is in another emaciated transitional state, playing a role taken by an original character in earlier drafts. Beevers’ performance is reminiscent of Ian McDiarmid as Grandad Palpatine: clearly untrustworthy yet simultaneously immensely persuasive.

The Master becomes a punchline

Anthony Ainley – who takes over from Beevers in ‘The Keeper of Traken’- clearly had a lot of fun playing the Master. Fans of computer game Destiny of the Doctors may recall how infectious Ainley’s enthusiasm for the role could be. Visually, his Master is reminiscent of Delgado, but he rarely has the same poise. Bluntly, there’s less dignity to the character. The chuckling, smooth façade is masking desperation, not anger. The quirks and regular mistakes Delgado’s Master made are now writ large in writing and performance. There is more than a hint of Alan Partridge as the Master scrapes through a series of ill-conceived low-stakes plans, somehow bouncing back. He becomes a punchline, an understudy, before again being reduced to mere survival. On a purely camp level, Ainley is great and memorably arch, but his incarnation unravels before us without explicit logic.

Eric Roberts is much simpler to deal with. For most of the 1996 TV Movie, his Master is written as an Americanised Roger Delgado and then, towards the end, we have both the camp and desperation of Ainley. Roberts may not be the most invested actor to play the part but he’s still having fun with it, playing the character bigger and broader than he’d ever been (and, we thought in 1996, as big as he’d ever get).

Before we talk about John Simm, Derek Jacobi is the final of the mayfly Masters. As Russell T. Davies observes on the DVD commentary for ‘Utopia’, Jacobi’s eyes convey so much of the character in his short screen time. Now we have Delgado and Ainley’s confidence, but the anger and sadism of Pratt’s Master is to the fore. It’s a handy and concise amalgamation of a lot of the character that leaves you wanting more. Jacobi also has a tiny, thespy outburst of ham to complement what’s come directly before and what’s about to arrive.

Mirroring the Doctor

John Simm’s Master, aka Harold Saxon, is not like Delgado’s in characterisation, but is also written as a comment on the current Doctor. This Master is, rather than an inversion, The Doctor as “The Big Bad” of the series in a post-Buffy TV landscape and so, given the Tenth Doctor, he’s fast-talking, quippy, mercurial (He sells himself as a messenger from the heavens at one point) and dangerous. The difference is that the Master embraces the latter.

Because these Doctor Who episodes were event television in 2007, we have the Master delivering on huge, complex plans that destroy millions of lives: beyond Delgado-level competence with beyond Ainley-level camp. Russell T. Davies is a big fan of tonal dissonance so we get the violence against women that Holmes hinted at with the Jack the Ripper connection, but in the same episode the Master prances along to The Scissor Sisters.

It’s important to make the distinction with Simm’s performance between personal taste and realisation of the scripts the actor is given. In terms of the latter, Simm delivers a big, cartoonish performance with a nasty edge because that’s what he’s been asked to do. Having carved a reputation with serious roles in Life on Mars, The Lakes and Cracker, Simm played against reputation. The character is written and performed big enough to make Eric Roberts seem the build-up rather than peak of the crescendo, managing to out-Tennant Tennant while baiting slash fiction writers.

A warped friendship

Continuing to explore The Relationship further results in Michelle Gomez’ Missy coming in with a finale-scale plan, with the reveal that the traditionally complex scheme is actually a warped gesture of friendship.

Missy’s character development builds on aspects of her predecessor – the nods to a deeper friendship are developed, but the crucial difference is when faced with a choice between death and being shackled to the Doctor for centuries, Missy chooses the latter and Saxon chooses death. This gives Gomez more to play with than Simm and she delivers on both the mania, as you’d expect Green Wing’s Sue White to do, but also brings out more enigmatic qualities.

While the gender-flip of the character coinciding with their softening is questionable, Gomez delivers the most poised performance since Delgado’s and also has a grumpy Doctor/fun Master inversion. And as for her final scene, it’d be a brave and/or foolish showrunner to return to the character soon after that.

Thirteen episodes later and mild-mannered Agent O turned out to be the Master in ‘Spyfall’. To be fair to all involved: hardly anyone expected this. Sacha Dhawan absolutely nailed the contrasts necessary for the reveal to work. His performance continues the manic rage and glee, but he has to do a lot with dialogue like ‘It’s red because it’s drenched in the blood of our people’ – a zinger that has all the rhythm of someone dropping crockery down an escalator. Dhawan’s Master doesn’t drive the story, instead being inserted into it to fulfil and explain story beats, and so he hasn’t had as much to work with.

Looking back, the Master has only really settled as a character in their last three incarnations, and while Roger Delgado’s incarnation is influential it’s in small ways. In fact Delgado’s incarnation is now something of an anomaly. While the basics of the character are largely intact throughout – evil and complex schemes that involve the Doctor – the character hasn’t been convincingly debonair since 1973. Instead the character has become more intense and manic. What connects the fan favourites is they’ve been asked to play interesting contradictions – unflappable despite their failures, vicious and violent despite their clear affection – so there’s more to them the peculiar tragedy of a recurring villain who never wins.