How Cardcaptor Sakura’s Queerness Broke Through Censorship

Despite heavy alterations for American viewing, Cardcaptor Sakura was still a gateway into queer relationships for young fans.

Picture this. It’s 2000. You’re sitting in your pajamas, munching on some waffles and waiting for Pokemon to come back from its commercial break on Kids WB. You’re hit with the usual ads for cereal, The Emperor’s New Groove, and X-Men Evolution.

Then, something different comes on. A promo for a show you’ve never heard of. A deep mysterious voice describes magical cards unleashing chaos on the world. You’re hit with quick cuts of a boy and girl fighting off magical creatures. You’re told by the oddly alluring narrator voice:

“Prepare for a quest unlike any you’ve seen before. Prepare for… Cardcaptors.”

You’re struck by it. The images. The sound. The voice. It feels different but familiar. You’ve seen some anime thanks to Pokemon and you can’t get enough of those trading cards so the phrase “Cardcaptor” sounds intriguing. You spend the next few weeks scanning the TV guide, waiting for this show to come out. And when it does, you fall in love.

That was, of course, my journey into discovering Cardcaptors. I had no idea then how much of an effect it would have on my life. I had no idea that this would be the show that, despite some of the heaviest censorship and edits ever seen in anime, would introduce me to queer characters for the first time. This was the show that made me realize it was okay to like men.

Despite what the oddly alluring narrator voice told me, I wasn’t prepared.

I didn’t know this at the time but Cardcaptors was an English reworking of the Japanese kids series Cardcaptor Sakura, originally released as a manga by the all-women artist group Clamp. The original series tells the story of young Sakura Kinomoto and her journey to retrieve the mystical Clow Cards in order to prevent a great catastrophe befalling the world. Each card she captures gives her new magical powers and she isn’t alone. She’s joined by magical boy/rival turned love interest Syaoran Li, her best friend Tomoyo, and mystical guardian beast of the Clow Cards/cute animal companion Kero.

It’s an extremely adorable series and for every intense action scene, like Sakura fighting off a giant dragon conjured from her friend’s imagination, there’s three adorable scenes with her doing low stakes activities like performing in a play or baking a cake. Cardcaptor Sakura is a series where the characters emotions and relationships take precedence over any action.

The supporting cast is full and rich but the two most important characters to mention are Toya, Sakura’s older teen brother, and Yukito, her brother’s best friend. Toya has a tough guy exterior but deep down cares about the people closest to him. Yukito is gentle, sweet, and loves to scarf down as much food as possible. The reason I bring them up is because they are very, very queer.

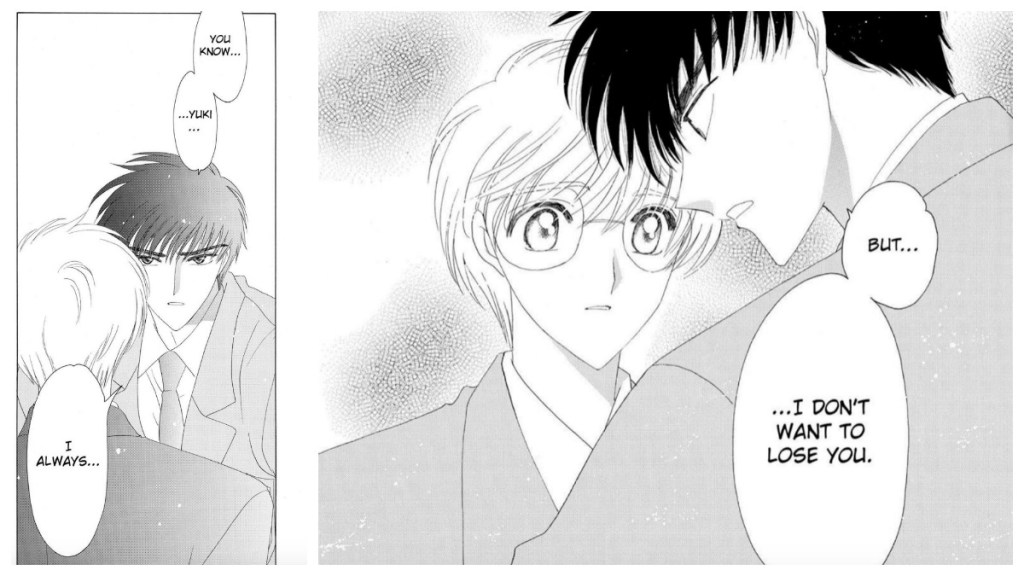

The two start off as close friends but it’s clear as the show goes on that Yukito and Toya are more than friends. Towards the end of the series, there’s a plotline involving Yukito slowly dying because he has a magical angel spirit inside of him (go with it) and doesn’t have enough energy to live. Toya, who had previously been established as having some magical power of his own, gives all of it to Yukito to keep him alive. This is especially powerful because that magic was the only way Toya could see the spirit of his dead mother.

When this happens the two characters are facing each other and Yukito as this angel spirit (no seriously, go with it) moves closer to Toya in what appears to be a kiss before he simply places his head near Toya’s neck. It’s a clear moment of the creative team not being able to go the full way in portraying them as queer but the intention is clear. This offering up of power can’t be interpreted in any other way than being romantic.

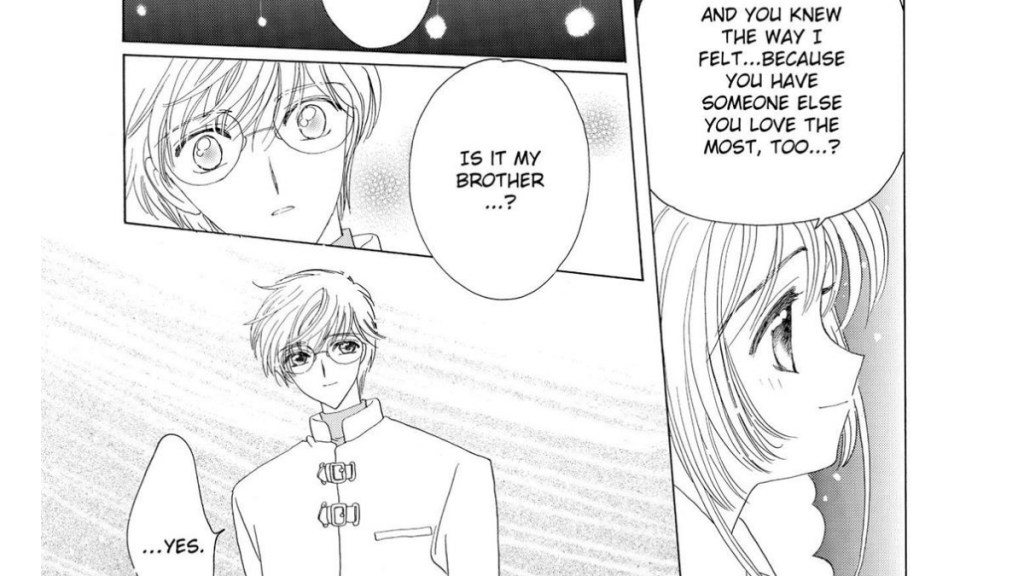

I’m sure it sounds like the show would keep their feelings ambiguous, trapped in subtext, but in the very next episode Sakura asks Yukito if he has someone he likes. He responds:

“…You could say that.”

Still subtext, right? Nope! Sakura, a ten-year-old girl, quickly follows up with:

“Is it Toya?”

To which Yukito replies, “Yeah… It is.”

He even refers to Toya as his “number one” and for the rest of the series the two share several scenes where they’re clearly affectionate for each other. It’s not subtext, it’s canon. The two have feelings for each other and they are queer.

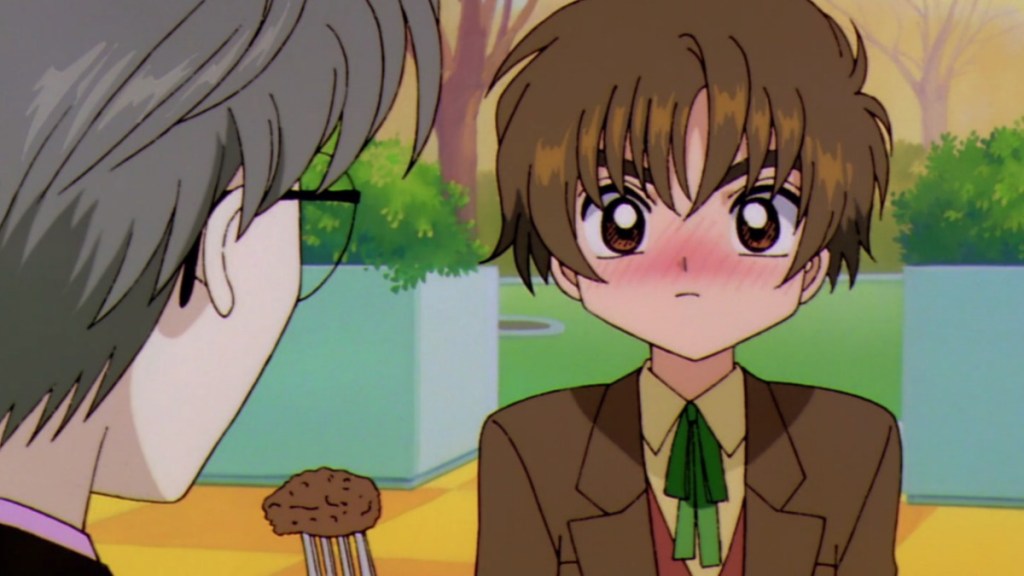

This isn’t the only case of queerness in Cardcaptor Sakura. There’s Tomoyo clearly being written as a lesbian and even Syaoran believes he has a crush on Yukito for a good chunk of the series. It’s later explained he was actually drawn to the angel spirit (you’re going with it!) inside Yukito but still, Sakura and Syaoran competed for the affections of the same boy for a good chunk of the show. That’d be a welcome addition to any kids series today but it was especially groundbreaking for kids to see it in 2000.

Unless you were a kid in America, like me. As previously mentioned, when Cardcaptor Sakura was brought over to North America it was adapted into Cardcaptors. All 70 episodes of the series were dubbed in Canada with some major edits occurring, including removal of any romantic pairings and especially the queerness. The scene where Toya (now named Tori) gives Yukito (now named Julian) his powers he actually says, “I don’t want to lose my BEST. FRIEND.” Wow. The conversation between Sakura and Yukito about who he likes is also changed to be Sakura learning “Julian” knows about his angel spirit.

The show was further edited when it was aired on Kids WB, with only 39 of the 70 episodes shown. More content was cut and some episodes were combined, mostly done to push Syaoran as a more important character and focus on the action in an attempt to appeal to boys. The Canadian dub of the show certainly changed many elements but the Kids WB version radically altered the show even further. They were going to make this a boys action series no matter what they had to do and you certainly can’t have queerness in a show in the early 2000’s, let alone one meant for young boys. Perish the thought that someone might see a boy crush on another boy! How will we live as a society?

The Kids WB version also edited the episodes where Toya gives his power to Yukito and Yukito confesses his attraction to Toya (originally two back-to-back episodes) into one single episode. This was likely done because they couldn’t skip the plot of Toya giving up his powers but they also wanted to minimize the queer content. (No copies of this edit exist online that I can find so I’m only working with my vague recollection of watching them as a kid.)

At the time, I didn’t know anything about this. I was nine years old and I didn’t look up the show on the internet. I just enjoyed it for what I thought it was: an action series with a unique look and a world I could easily imagine myself in. I went out to a Toys “R” Us and bought a set of Clow Cards (which I still own to this day.) I drew fan art. I even wrote some fan fiction that featured zero paragraph breaks across three full pages.

And I still picked up on the queerness. Not directly, mind you. I was nine years old and still hadn’t had my first crush yet. But even with all the edits in the show, I could feel there was something more going on between the characters. The most obvious was Sakura and Syaoran’s relationship which, for as many rewrites as they tried to shove in, couldn’t be hidden.

Syaoran’s crush on Yukito, rewritten to be Syaoran simply being afraid of him, still shone through. They weren’t able to change the animation and despite what the characters said I could see Syaoran blushing when Yukito appeared. That boy was not straight.

Nor were “Tori” and “Julian.” You can’t escape the queerness inherent in those Clamp designs. I didn’t know it at the time but the two fell into the shojo/yaoi trope of queer male couples featuring one masculine man and one feminine one. The way “Tori” looked at “Julian” and even the way the two talked about being BEST. FRIENDS. still had a queer energy to it. My young queer brain could sense it. I especially gravitated to “Tori,” who also displayed an interest in woman as well, making him bi or pansexual.

I wouldn’t have been able to put into words at the time but I knew the show wasn’t as straight as it was trying to pretend it was. You can change the words but the powerful queerness in that animation? You can’t get rid of it. It had a power over me I wouldn’t be aware of until later.

When the show left the air in 2003, I was heartbroken. At that point I still had dial-up so I had no way of watching the series ever again outside of a few episodes recorded on VHS. I knew there were more episodes, thanks to footage from the cut episodes appearing in bumpers and promos but I never thought I could.

In the years following, I would see glimpses of the uncut Cardcaptor Sakura DVDs that were released by Pioneer Entertainment at my local video shop (which was the first confirmation I had of its original title) but I wasn’t allowed to rent them since they were rated 13 and up. Being placed near some fairly adult anime didn’t help matters. I just assumed I’d never get to see more of Cardcaptors or Cardcaptor Sakura.

Then, in 2004, a friend showed me the Cardcaptor Sakura manga. I distinctly remember it was the second volume in the “Master of the Clow” arc and I could barely believe it. More Cardcaptors! I shook with excitement holding it, desperate to look at every page before my friend snatched it away from me. It was more of what I loved… and then I saw these pages.

What had been hidden before was now out in the open. These two guys were more than friends. Toya (this was a faithful translation) clearly had feelings for Yukito. I had to read more. I patiently waited months until I got a gift card to a bookstore and snatched up several volumes, including the fourth in the “Master of the Clow” arc.

Boy let me tell you, if I didn’t realize I liked men… this manga did it. The fourth volume includes the scene where Yukito admitted his feelings for Toya without any censorship. My mind couldn’t process what I was seeing. This was a guy who liked guys… and everyone supported him in it! It was treated as a normal thing, with Sakura proudly proclaiming she’d punish Toya if he picked on Yukito. It was not only charming and adorable, it was the first time I’d ever seen an openly queer character.

Because of Toya and Yukito, I was able to figure out my sexuality in a safe way. I wasn’t afraid of the slow realization that I liked women and men; I knew it was okay because Cardcaptor Sakura showed it was okay. Toya being bi or pan really helped as well, especially since none of the characters treated it as if it was a problem or out of the ordinary. No one else in my life had ever told me about queer people so I’m very fortunate that the one piece of media I had that featured them was so positive and uplifting… and I wouldn’t have found it without Cardcaptors.

I know it’s weird to praise the series with its heavy censorship that tried to hide all the queer elements but without it I never would have found the most positive, uplifting, and validating piece of queer media when I needed it the most. They tried to keep it hidden but queerness will always shine through and the people who need it the most will do whatever they can to find it.

What I’m basically saying is that Cardcaptor Sakura was so queer even two layers of censorship editing couldn’t hide it forever.

Many years after I read the manga, I finally got my hands on the complete uncut Cardcaptor Sakura series and smiled the whole way through. Finally, after fifteen years, everything I ever suspected about the series was shown to be correct. Toya and Yukito were queer men who had feelings for each other. Syaoran wasn’t straight. It was overall a much better show. Putting aside my heavy nostalgia for that Kids WB airing, Cardcaptor Sakura is a wonderfully cute series about big feelings that merely uses the card capturing action as an extra spice. The real meat of the show is Sakura and her friends just living their lives and the challenges that come their way. They’re pretty low stakes but for the young characters they feel just as huge as the mystical cards.

It’s not flawless by any stretch of the imagination; there are some dicey elements with some of the relationships that keep the series from true perfection. Still, Toya and Yukito can’t be ignored. Nor can Sakura herself who even through the heavy censoring of Cardcaptors was still a hugely positive girl role model for me to have at such a young age. Seeing her acceptance of Yukito and her brother was almost as powerful as seeing Yukito and Toya together.

With the show now on Netflix in its original form along with a more faithful English dub, I’m excited for a whole new generation of kids to experience the series. I hope they’ll be just as comforted and validated as I was.

While I’m glad the Kids WB and original Canadian dubbed versions of Cardcaptors aren’t easily accessible anymore, I can still appreciate it as a gateway into discovering the franchise as a whole. Without it, I would never have found the manga. Without that, I might not have been so comfortable in my sexuality from such a young age. I might have taken much longer to come out. I might not have met my partner who I now live with in a fabulously queer relationship.

Cardcaptor Sakura helped me be who I am today and, despite all its censorship, Cardcaptors played a major part in that. (And the theme song is still a banger.)

Note: I know I glossed over Tomoyo being a queer woman in this article and I think there’s a lot more that could be said about her. However, her crush on Sakura (who’s her cousin) was something I didn’t feel comfortable writing about here.