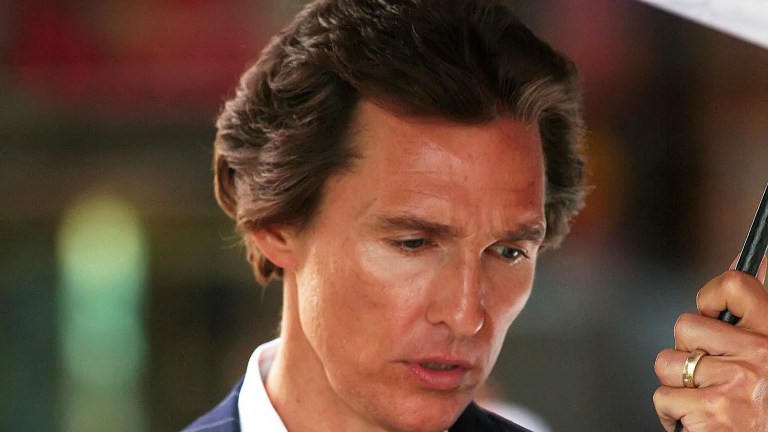

How Matthew McConaughey’s Chant Scene Changed The Wolf of Wall Street for the Better

One of the best recurring motifs in The Wolf of Wall Street wasn’t even in the script, but that changed when Matthew McConaughey showed up.

Matthew McConaughey is barely in Martin Scorsese’s The Wolf of Wall Street. But back in 2013, you probably wouldn’t have guessed this after watching the trailer. Marketed around McConaughey beating his chest as if he were part-caveman and part-that guy who thinks he can appropriate a Native American chant, the actor’s rhythmic hum while pounding his pecks is strangely hypnotic. And as it turned out, it’s at the heart of the movie, even if McConaughey only appears in three scenes.

Entering and exiting the film inside of The Wolf of Wall Street’s opening 15 minutes, McConaughey’s Mark Hanna is positioned as a semi-mentor of all things Wall Street (at least as far as Scorsese sees it): corruption, avarice, lust, and, of course, cocaine. In a more heavy-handed movie, Hanna might be positioned as Lucifer, a dark angel who would buy the soul of Jordan Belfort (Leonardo DiCaprio) by way of seductive speeches on why greed is, actually, good. However, Scorsese never makes the mistake of imagining Belfort had much soul to begin with—or at least not by the time he arrived on Wall Street in 1987.

As far as the film is concerned, Jordan is already a hellbound little shit, and Hanna not so much corrupts the stockbroker-in-training as shows him the first shortcuts in the game.

“How the fuck else are we supposed to do this job?” Hanna demands. “Cocaine and hookers, my friend!” As far as Scorsese and the Terence Winter screenplay is concerned, this was the beginning of Jordan’s real vocational education. On paper, it’s already pure stuff, but what makes the sequence sing is an improvisation which McConaughey never even intended for the camera.

During an interview with The Showbiz 411 back in 2013, McConaughey revealed the chest-thumping was an acting exercise he’d done for years to prepare for a scene and get into character.

“That’s something I do from time to time to relax myself before a scene or to get my voice lower,” McConaughey said. “[I] do it to whatever rhythm of the character is in the scene. And I was doing it before takes, and Leonardo had the idea of saying, ‘Why don’t you put that in the scene?’ So I did.”

It was a canny choice, one which McConaughey said appealed to Scorsese’s sense of musicality. By the end of McConaughey’s days on The Wolf of Wall Street, the director was even communicating with the star through grunts that would’ve done Hanna proud: “After the last few takes, he and I didn’t even really speak that much English. He was just doing sounds. He loved the nonverbal thing.”

Scorsese’s smittenness makes sense. McConaughey’s flourish added so much to the film, including when much later in the narrative (and years afterward in the characters’ lives), DiCaprio’s Jordan Belfort co-opts the chant while deciding he’ll refuse to take a plea deal that would give him immunity from federal prosecution. Instead he screeches with the fury of Charlie Manson to his cult of crooked finance bro minions, “I’m not leaving!” He then leads his crooked lemmings in a braggadocious riff on McConaughey’s acting exercise.

The appeal of the rhythmic thumping, like many of the pleasures and revulsions of The Wolf of Wall Street, is primal. It’s a nonverbal way for McConaughey to adjust his mindset in reality, but onscreen it allows for a different type of reality distortion for Hanna and Belfort. The moment, after all, comes during the same sequence where Hanna tells Jordan, “We don’t create shit, We don’t build anything.” The act of moving people’s money around while taking home a commission is, as Hanna proudly admits, fairy dust.

This is the intellectual paradox wherein Scorsese wants the picture and audience to live: a confounding irony that we as a culture tacitly permit, as the greediest indulge in mountains of excess—which is in turn mirrored by the film’s own lascivious indulgences. All the characters’ careers, as Jordan later says in voiceover, is to figure out how to spend clients’ money for them, because the suckers simply don’t know how to enjoy it. Yet that superior and refined enjoyment still ultimately comes down to “hookers and cocaine.” Or in Belfort’s case, Quaaludes and multiple wives.

Despite this reality, men like Hanna, Belfort, and the other self-appointed masters of the universe romanticize these efforts as heroic and mythic deeds. It is simultaneously intellectual “acidic, above the shoulders mustard shit,” as Hanna declares while justifying his need to masturbate in the company bathroom, and an overly masculine pursuit.

But while we can interrogate this irony with all the above the shoulder mustard shit words we want, the image of McConaughey getting DiCaprio to beat his chest alongside his own in rhythmic harmony is so much better at succinctly, and emotionally, communicating that. You feel the spark of unchecked avarice spreading, jumping from one link of wood to the other. Lizard-brain thinking has caught fire.

Two guys sitting in a posh Lower Manhattan restaurant with panoramic views of the skyline behind them, and martinis in their hands, think they’re not only on top of the world, but the salt of the earth. It’s a lie they tell themselves, one which they’re too deluded to see, even as Scorsese invites you to recognize it on your own. By its very nature, everything about The Wolf of Wall Street is excessive, right down to its running time. The film doesn’t know when to stop, because Jordan also never knows when to call time.

So instead of ending triumphantly at the end of a pseudo-third act where he nearly dies during an epic overdose of ‘Ludes, Jordan continues to beat his chest like a wannabe strongman for the mob, leading them into a whole extra reel where he eventually sells them all out to save his own skin. In the end, this chanting master of the universe can’t see the irony that he winds up a wife-beating, child-terrifying, schmuck crying in front of his parents when the real bill comes due. Still, the movie knows many of its viewers will nonetheless idolize him, hence the ending where it asks who is the bigger chump, you or him?