The Best Letters Film Directors Sent to Projectionists

Personal letters from Lynch, Spielberg, Kubrick and other directors who care enough to make sure we see their films properly

This article comes from Den of Geek UK.

Most film directors don’t actually need to go to the cinema. If you have anything to do with the movie industry, you’ll probably see most new releases in a screening room – a lovely luxurious little booth somewhere in Soho or Burbank where you sit on leather sofas, get free drinks and watch films on pristine, perfectly calibrated, endlessly color-corrected screens with crystal clear surround sound.

If something goes wrong with the picture, the projectionist will know – because they’re standing right behind you. In short, it’s a very, very long way from how the rest of us gets to watch films.

Movie theaters have generally improved a lot over the last few years (helped in no small part by the 3D revolution that pushed all the big chains towards getting digital projectors), but seeing a film at your local multiplex is still a gamble that might not pay off.

“Other people” still tends to be the biggest complaint levied at cinemas (and the biggest levied back by the staff who work there), but the quality of the sound and picture is also a common issue. Often too dim, too quiet, not-aligned properly or not in focus, it’s the projectionist’s fault if everything you’re seeing and hearing isn’t exactly as it should be. But with most projectionists at multiplexes having to look after several screenings at once, often under tough time pressures, mistakes are all too easy to make.

Screening problems are slightly annoying if you’ve just paid a small fortune for the whole family to go the cinema – but slightly more so if you’re the person who just spent four years of your life, millions of dollars and your entire reputation making the film… Some directors might not spend a lot of time in a real cinema with real people, but they’re all too aware that most of us don’t get to see their films the way they should be seen.

The majority of filmmakers have to hope for the best – trusting that projectionists around the world know how to do their job properly – but a select few have taken to attaching personal letters to their own film reels, making a few friendly suggestions about how to not mess up their life’s work.

David O. Selznick

The first person to give this a go was David O. Selznick. He didn’t direct 1939’s Gone With The Wind (that was Victor Fleming), but he might as well have, famously lording it over the whole production on-set and off. His control obviously stretched to the film’s release too, as this letter shows. To be fair, he’s quite reasonable about the whole thing, sending a little booklet to projectionists on possible lighting and sound issues and addressing them as “the link between the producers and the public”. Also, the film is almost four hours long, which must have been a nightmare to screen in the old days when the reels needed to be constantly changed.

Brad Bird

Most recently, Brad Bird tried the same thing for The Incredibles 2 – resorting to using a lot of capital letters to empower projectionists around the world to DELIVER QUALITY on the GIANT screen so everyone who LOVES movies can have the best THEATRICAL EXPERIENCE. That means making sure the picture is bright, the image is focused, and the audio levels are properly tuned to ROCK THE HOUSE. How ever annoying it must have been to receive this letter in a dingy cinema booth, you have to love Bird’s ENTHUSIASM.

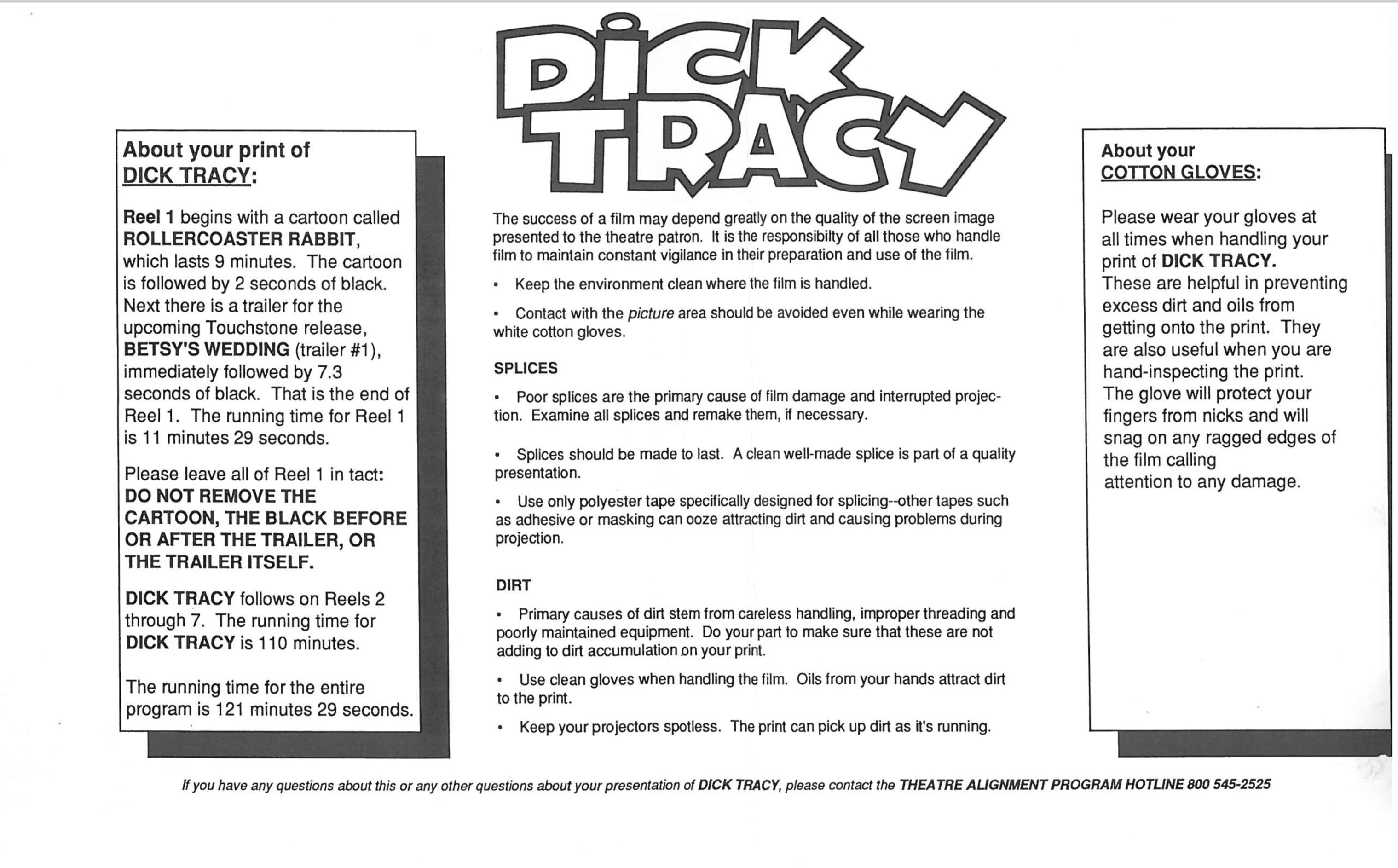

Warren Beatty

It’s one thing to politely ask a projectionist to check the volume is turned up, but it’s another thing to tell them to wear white cotton gloves every time they touch your film. Technically, a projectionist is supposed to wear gloves every time they handle any of the reels – but Beatty was obviously concerned about the print quality deteriorating for his 1990 film, Dick Tracy. The original run of the film was actually slightly more complicated than usual – including a cartoon short and a trailer cut into the start of the feature – aiming to recreate an old-fashioned matinee show.

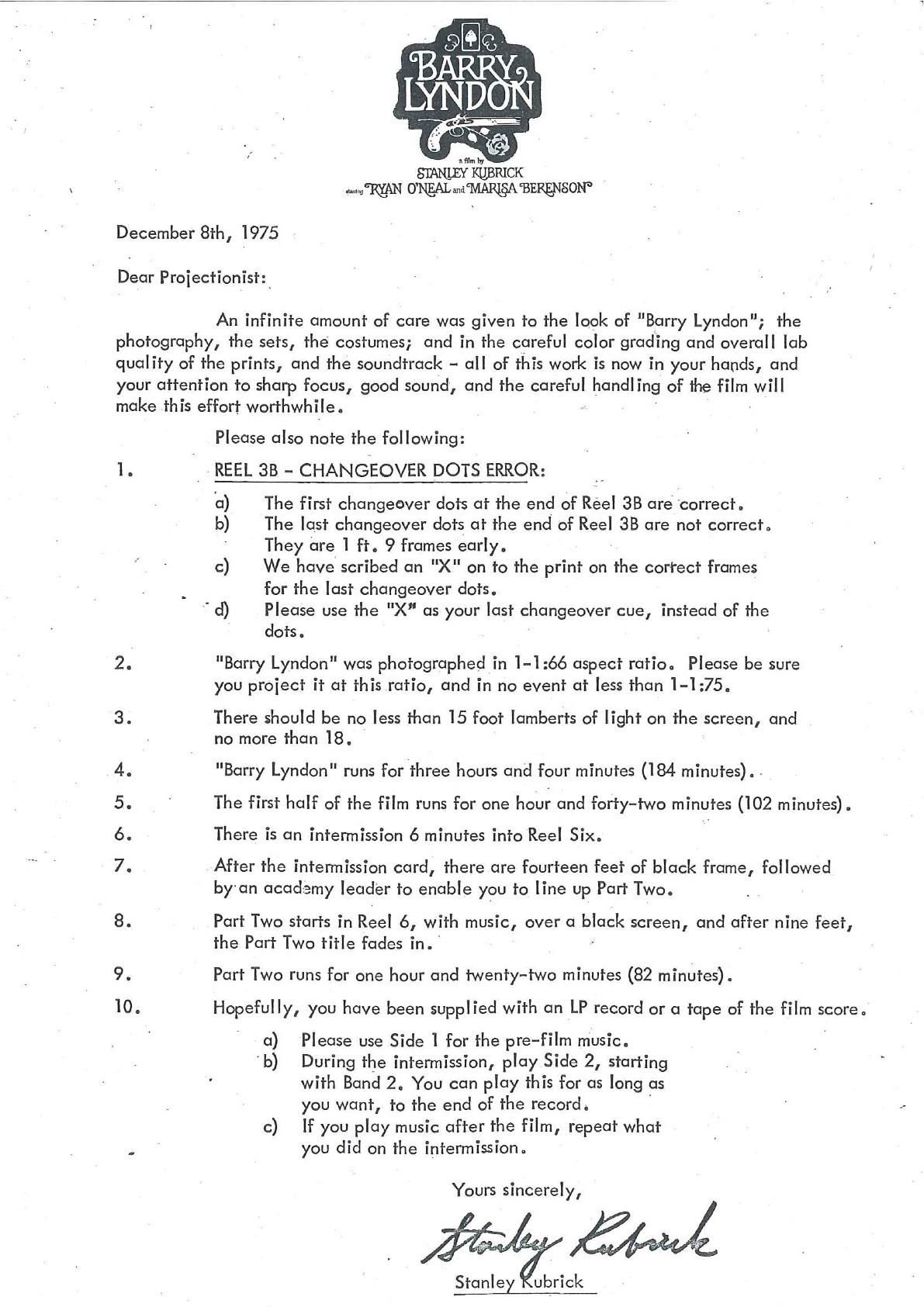

Stanley Kubrick

Stanley Kubrick was notorious for being a perfectionist on his film sets (some would say “control freak”, others still, “a complete monster”) so it’s no surprise that he wanted to make sure everything was equally perfect in the cinema. Writing a set of neat, precise instructions for the release of 1975’s Barry Lyndon, you can almost hear Kubrick’s palm sweating as he writes “all of this work is now in your hands…”

Barry Lyndon included several tricky changeovers (one of which was incorrectly flagged, according to Kubrick), a lot of gloomy shots that could be ruined by poor screen lighting and one intermission – which should properly be accompanied by the supplied LP of the film’s soundtrack (you should only play side two, band two, but you can play this “for as long as you want”).

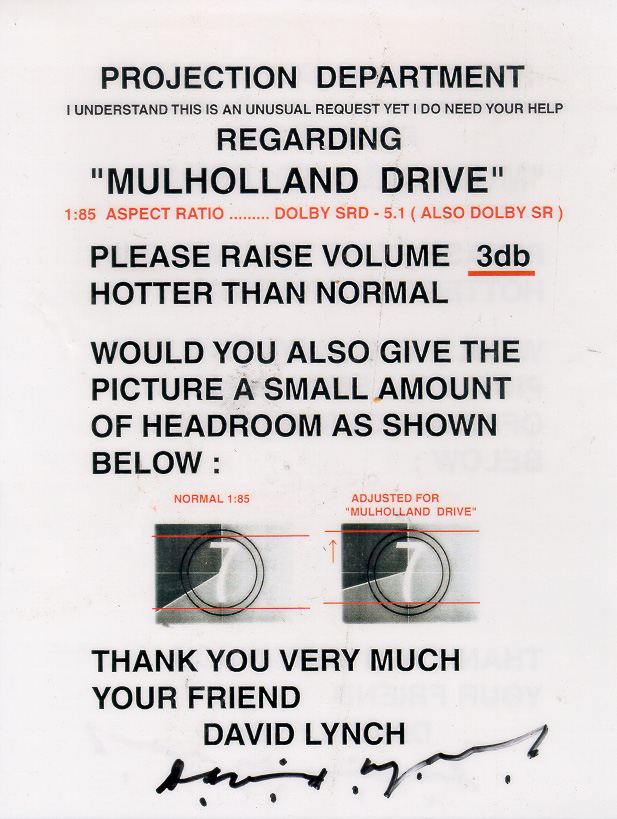

David Lynch

“I understand this is an unusual request yet I do need your help” begins David Lynch, keeping things brief for his note on Mulholland Drive with two fairly simple requests to the projectionist about sound and alignment. With at least three separate storylines that don’t actually meet up and a third act that recasts one of the main characters as someone else entirely, Lynch might have been better off explaining what order to run the film in (or perhaps just telling us what was in that damned box…).

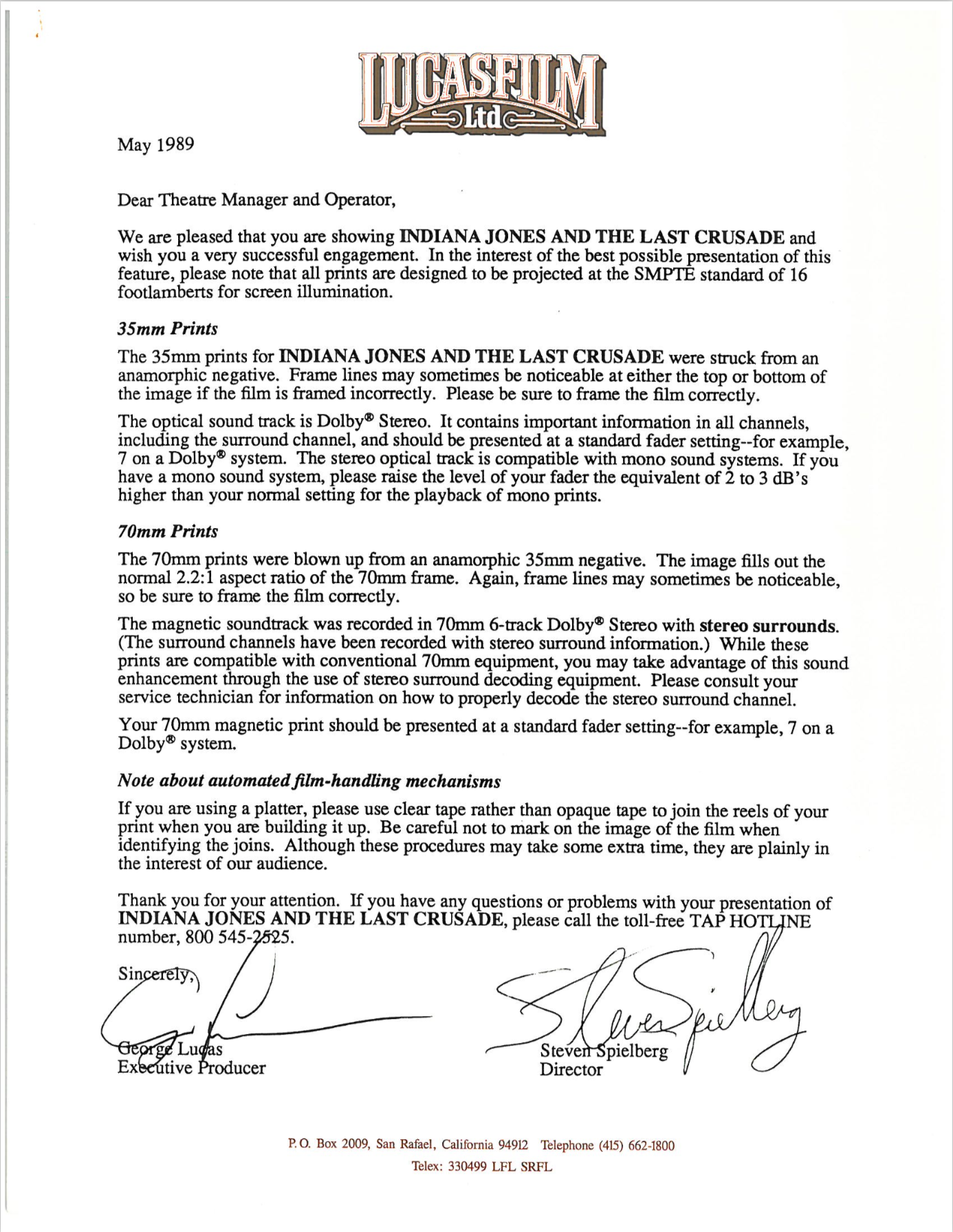

Steven Spielberg

A lot of the concerns that directors seem to have are around the 70mm prints of their films. In the old Panavision days, projectionists would have been experts at threading giant widescreen reels, but most modern technicians wouldn’t have had much practice. When Indiana Jones And The Last Crusade was released in 1989, it came in two sizes – 35mm for regular cinemas and (blown-up) 70mm prints for any that still had the technology to show it. This was before the introduction of massive IMAX reels – and way before Quentin Tarantino caused problems for cinemas around the world with his retro-sized Hateful Eight print – so Spielberg and George Lucas sent a nice note to warn projectionists about the potential quirks of the system.

Michael Bay

For a lot of directors, 3D was an even bigger problem than 70mm. Back in the late ’00s when everyone was releasing a film in 3D, films would often look a bit dark and gloomy if the cinema you were in wasn’t properly equipped to turn the brightness up. The average quality of 3D screenings probably played a big part in (mostly) ending the over-reliance on the technology, but not before most multiplexes switched to modern digital projectors to save themselves the hassle. Releasing Transformers: Dark Of The Moon in 2011, Michael Bay didn’t want the dark of the moon to look too dark, so he sent an inspirational letter to the projectionists, reminding them that “we are all in this together.”

Trying to “make the audience believe again” using Transformers 3 probably wasn’t the best idea though.

David Yates

If you’re a projectionist who needs a bit of real inspiration, take a look at David Yates’ letter for Harry Potter And The Deathly Hallows: Part 2. Polite, friendly and very English, Yates gently reminds the reader that they’re holding the last part of a “ten-year movie experience” that “literally thousands of people” have helped to make. “In my mind you are the extra member of our crew”, he continues, adding that the way they do their (comparatively low-paid) job is going to make or break the whole series. And he’s right, this stuff really does matter – and it’s genuinely nice to know that some directors care.