Pi: Darren Aronofsky Reveals the Secrets of Making the Ambitious Sci-fi Movie

Exclusive: Darren Aronofsky reflects on mind-bending Pi, the movie that launched his career and that's celebrating its 25th anniversary with a new restoration.

The late 1990s might be remembered as a pretty good time for science fiction at the movies. There were Hollywood blockbusters with origins in sci-fi literature (Starship Troopers, The Fifth Element, Contact) and loaded with VFX razzle-dazzle, while at the same time smaller and/or independent productions were offering up more cerebral, complex, concept-driven ideas (Cube, Dark City, Gattaca).

Nestled in the middle of all this, appearing in theaters at the tail end of 1998, was a film that was perhaps the tiniest of all with regards to budget and production, but at the same time one of the biggest in terms of its central premise: Pi (aka the Greek letter π), the writing and directing debut of filmmaker Darren Aronofsky that tackled numbers theory, Jewish mysticism, and the meaning of all existence, all within 80 minutes and largely confined to one main (very cramped) set and a handful of characters.

If you’re lucky enough to live in a participating city, Pi is returning to the screen Tuesday (March 14 – “Pi Day”) in a new 8K restoration with Dolby Atmos sound for IMAX. That’s a significant upgrade for a movie that was shot on black and white 16mm reversal stock (a kind of film stock that produces a positive image right away, skipping the expense and time of processing first a negative).

“That’s been the really exciting thing about going back to a film that was finished purely photochemical and was mixed in stereo sound,” Aronofsky tells Den of Geek. “When you look at the tools that we now have as filmmakers, versus the tools 25 years ago, it’s remarkable how much it’s all changed.”

A Small Movie With Huge Ideas

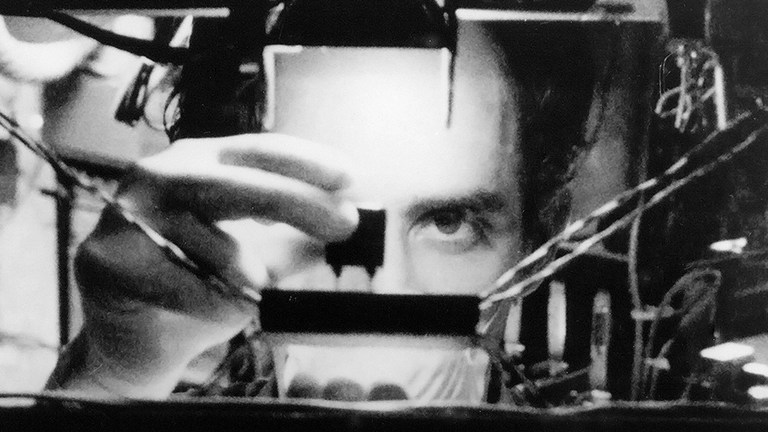

One thing that hasn’t changed while watching the film today is the audacity and originality of its ideas, and the way that Aronofsky and his team of guerilla filmmakers present them. Pi tells the story of Max Cohen (Sean Gullette), an out-of-work mathematician who lives alone in a small Chinatown apartment where most of the space is taken up by his makeshift, cobbled-together supercomputer Euclid.

Max – who suffers from paranoia, paralyzing headaches, and borderline personality disorder – is trying to determine whether numbers can account for patterns in everything from the stock market to nature, and while programming Euclid to make stock market predictions, he fleetingly comes across a 216-digit number he’s never seen before – along with a correct prediction for one stock.

Max seeks advice from his now-disabled professor, who is unnerved to hear about the number, which he encountered himself many years ago. As the number literally seems to infest Max’s brain, he is pursued by both a predatory Wall Street investment banker and a congregation of Hasidic Jews: the former is convinced that the number can accurately map out the rise and fall of the stock market, while the latter are certain that the number is the name of God and will herald a new age.

Pi (the title itself refers to the ratio of a circle’s circumference to its diameter, resulting in a theoretically infinite, not-repeating number) deals with the idea of finding order and meaning in the seemingly random nature of the universe, whether through financial numbers or religious beliefs, and how the pursuit of that order can drive a basically well-meaning person to madness.

“I used to joke back then that I couldn’t afford outer space, so I went to inner space,” says Aronofsky. “So I got into basically the psychology of the character and the POV of the character…I clearly couldn’t do a space movie with the limitations I had. So I had to figure out how I could get some of these big ideas into the mind of this character and dramatize them.”

Kabbalah and Crowdfunding

Aronofsky says that Pi emerged out of both the challenge of making a movie with limited resources as well as the “jigsaw puzzle” of various ideas that he had been fascinated with throughout the 1990s. “I probably had been moving the pieces around my head for most of the ‘90s,” he recalls. “I just took a lot of the different things that I had been interested in at the time, from all the different books I was reading, all the different stories I was thinking about, all the different landscapes I was hanging out in, and kind of blended it all together into what eventually became Pi.”

Among the elements that found their way into Pi were the idea of spirals cropping up in everything from the shape of DNA to the structure of galaxies, to Kabbalah, the ancient form of Jewish mysticism that offers up (and we’re simplifying here) a sort of secret history of the universe and its connection to God. Aronofsky says that these subjects were all intriguing to him at the time, although it was harder back then to find information on them.

“Kabbalah wasn’t really a big thing at that point,” he says. “It hadn’t really gotten that popular. Neither was sort of this sacred geometry stuff. It was hard to find any information on it. It was early days of the internet, so there wasn’t that much stuff out there on it. We had to find a lot of different fringe press that was floating around and order books that would take a couple of months to get the references.”

With the help of longtime friends Sean Gullette and Eric Watson (who was the producer on the film), Aronofsky hammered out the script for Pi – then he and Watson had to raise the money to shoot it. They eventually managed to scrape together around $60,000 by asking friends, family members, and other interested parties to invest – all before the era of online crowdfunding and applications like Kickstarter.

“We didn’t have any really rich patrons to help us,” says Aronofsky. “So someone had the idea of just sending these letters out to everyone we knew, asking for $100, with the promise that if the film made money, they’d get $150 back, and they’d definitely get their names in the credits. So it’s kind of a long credit roll, which is fine for a 79-minute film. But everyone got their money back, which was a beautiful day when we got to distribute the checks. But yes, I could have stopped becoming a filmmaker and invented Kickstarter and probably done a little better.”

Martin Scorsese Inadvertently Helped Make Pi

Most of the film was shot in a warehouse in the Bushwick neighborhood of Brooklyn, where the main set – Max’s apartment – was constructed. For other scenes around New York City and in the subways, Aronofsky and his crew shot guerilla style, grabbing shots illegally instead of applying for expensive permits from the city. Aronofsky recalls one such scene, in which Max hallucinates finding his own brain on the steps of a subway platform, benefiting from the presence of another film being shot nearby.

“We had the brain lying on the steps with Sean leaning over it, and suddenly we all looked up and there was this cop staring right down at us,” Aronofsky says. “She just looked at us, grinned to herself and walked off. We had no idea why she didn’t bust us. A few hours later we came back up and told our producer what happened, and he pointed across the street and [Martin] Scorsese was shooting down there. So I think she probably thought we were part of that shoot or something, so we got away with it.”

Although he’s come a long way from stealing shots on subway platforms, the experimental nature of Pi and its eccentric blending of genres set the tone for the next 25 years of Darren Aronofsky’s career. From the sci-fi concepts of The Fountain to the alternate Biblical history of Noah to the psychologically damaged protagonists of movies like Black Swan, The Wrestler, and his latest, The Whale, many of this filmmaker’s thematic concerns can trace their origins back to that tiny little New York indie about numbers, patterns, ancient texts, and the meaning of the universe.

“I mean, I hope I’m not a one-trick pony,” says Aronofsky with a laugh. “But yeah, of course, there’s certain things that I’ve have found interesting that I continue to pursue and think about and I imagine that kind of taste has made me chase certain ideas and stuff.”

The restored version of Pi is playing at selected IMAX theaters on March 14.