Persuasion Discourse Has Revealed Racism in Jane Austen Fandom

There may be valid criticisms of Dakota Johnson's Persuasion, but the gleeful vitriol leveled against the movie and its inclusive cast reveals insidious gatekeeping of the Jane Austen canon by so-called fans.

Netflix’s Persuasion starring Dakota Johnson as Anne Elliot and Cosmo Jarvis as Capt. Wentworth has become a very controversial adaptation of Jane Austen’s novel since debuting on Netflix, with many critics and writers already debating the pros and the cons of the movie. However, in my personal opinion as an Afro-Caribbean American Austen fan, there has not been enough discussion of the harm racists and gatekeepers have done with the way they have engaged in discussing this movie.

I personally experienced the wrath of Austen fandom racists during “PineappleGate” and know that the debates over the merits of director Carrie Cracknell’s Persuasion are hiding deeper issues. They also repeat the same patterns.

While the vast majority of good faith critiques by professional critics, as well as fan reactions, stuck to discussing elements of Persuasion that were separate from race, chatter on Facebook and other social media sites reveals that racists are hiding behind fair game adaptation critiques because they serve the purpose of convincing BIPOC and new viewers not to watch the film.

Although Johnson’s Anne is white in the movie, she is surrounded by many more characters of color compared to past adaptations. Anne’s sister Mary (Mia McKenna-Bruce) is married to Charles Musgrove (Ben Bailey-Smith), and their children are biracial. Charles’ sisters Louisa (Nia Towle) and Henrietta (Izuka Hoyle, who is best known for her role in the West End cast of Six the Musical) are also diversely cast, and their melodrama, gossip, and hyperactivity represent the opposite of Anne’s mourning and frustrated existence.

Lady Russell (Nikki Amuka-Bird) who initially advised Anne not to marry Wentworth but then has a change of heart is also Black. Their presence in the space of the film is normalized and the film also wisely makes the choice to not break the escapism by answering questions of how the Musgroves and Lady Russell have obtained their status in society, thus avoiding some of Bridgerton’s pitfalls with juxtaposing history and fantasy.

Meanwhile Henry Goulding as Mr. Elliot is a bold experiment in racebent casting in a Regency-set period drama. Goulding was offered both Wentworth and Mr. Elliott, and chose to stretch his acting skills and play an antagonist. In the story, Mr. Elliot has a roguish agenda to stop Anne’s widower father Sir Henry Elliot (Richard E. Grant) from remarrying and disinheriting him. He’s intrigued by Anne but Anne sees his presence as a distraction best kept at a distance.

While I will leave the ultimate call on stereotypes such as the “yellow peril villain” in relation to Mr. Elliot to Asian viewers, Persuasion is still going in the right direction in regard to expanding East and Southeast Asian representation in UK period dramas. It is clear some women wanted the chance to fetishize Goulding the way they did Regé-Jean Page from season 1 of Bridgerton and threw a tantrum at the trailer, because romance/period drama fandom struggles with rooting for antagonists/villains compared to other fandoms.

Persuasion picks up where Mr. Malcolm’s List left off by featuring Ashley Park and Naoko Mori. Bridgerton in contrast mainly featured East Asians as very minor or background characters. East and Southeast Asian representation in UK period dramas in the past decade has focused on stories far away from the Regency era: the cleaned up but still problematic Yi Tien Cho story in Outlander Season 3, the blocked by copyright law from US viewing WWII era miniseries, The Singapore Grip, and more recently the Hong Kong set episode of the BBC/PBS miniseries Around The World In 80 Days. No matter what viewers decide on this adaptation’s approach to Mr. Elliot, we need more diverse representation in future Austen adaptations and non-Austen period dramas overall.

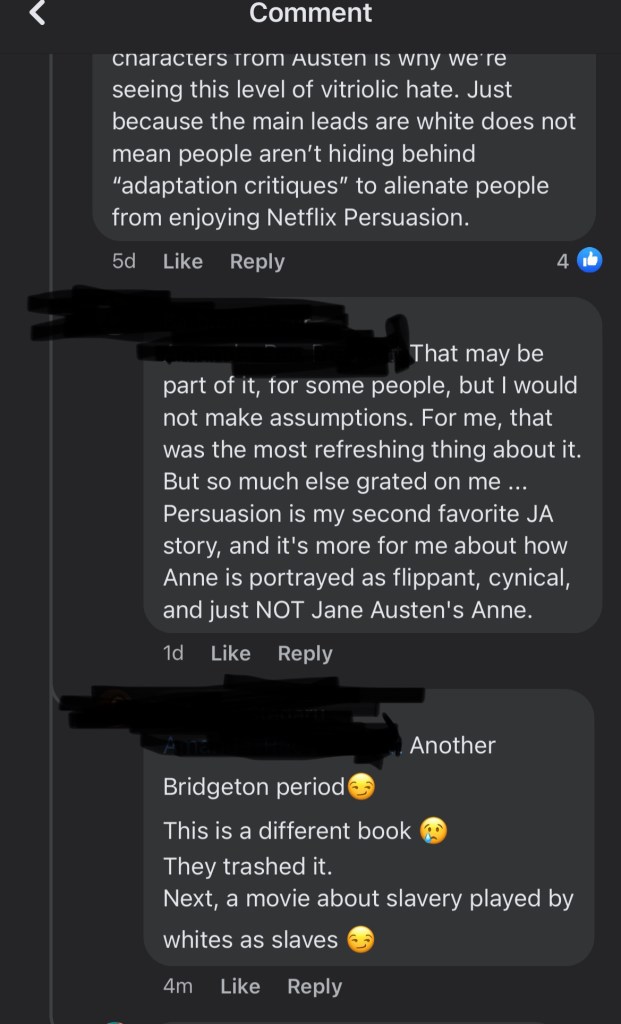

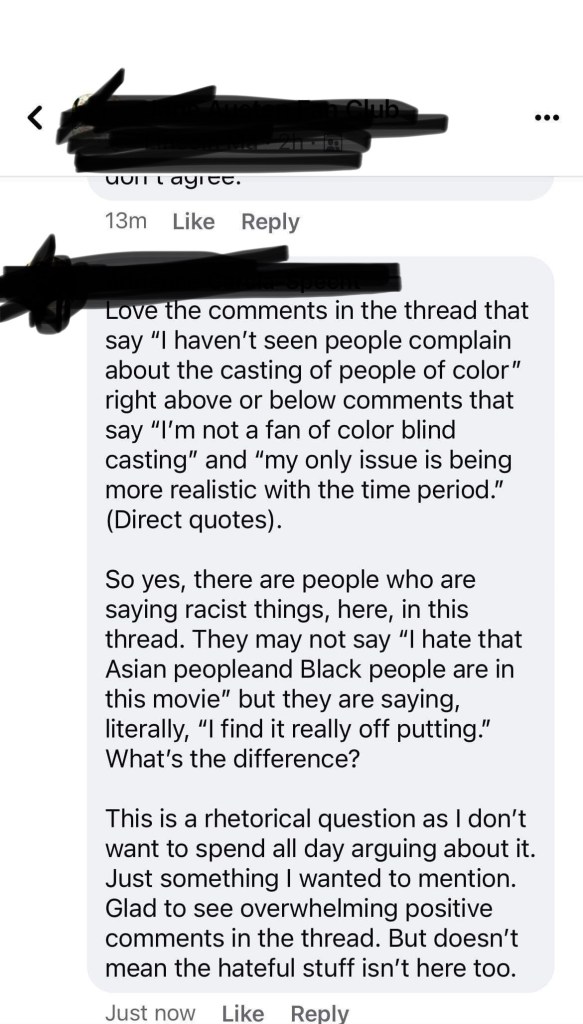

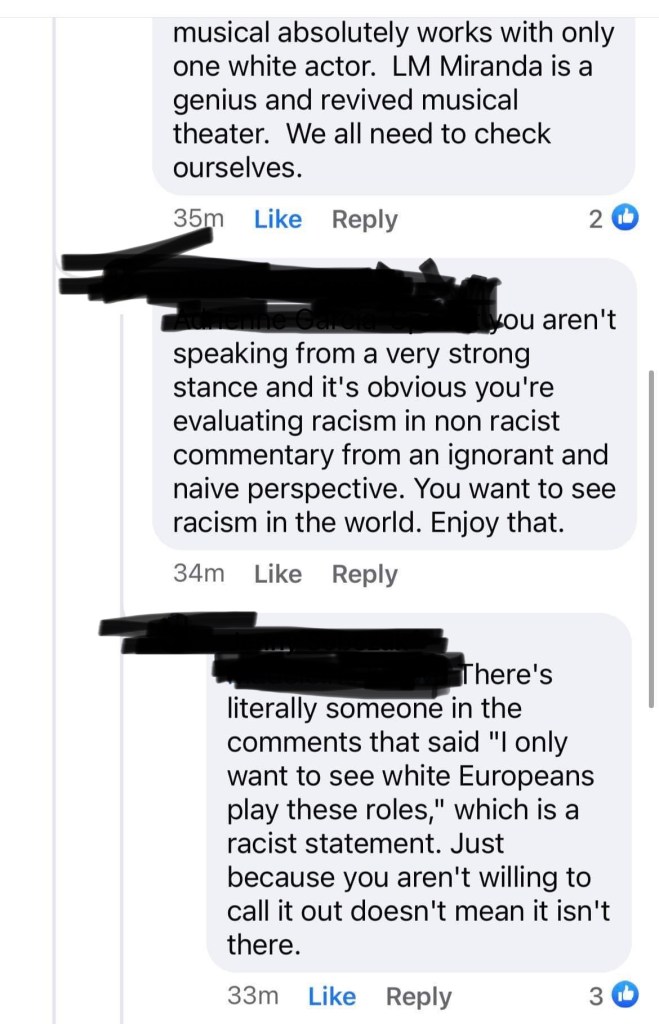

Sources sent me these screencaps from a popular Austen Facebook group which proves that people are hiding behind dog whistles. ”Historical accuracy” is a well-known dog whistle to justify attacks against inclusive casting. They also specifically reference Bridgerton as a negative influence, which is also pervasive, problematic element in fandom.

This two part thread shows how a BIPOC Austen fan was criticized by for pointing out racism. Fortunately they were supported by a white fan:

Similarly, Austen blogger Black Girl Loves Jane faced passive aggressive comments on one of her Facebook group discussion posts. When she confronted other members for criticizing the movie over casting Black actors, admins shut off responses to her post. She also found racists disguising their feelings about the movie with meme humor. The meme maker Photoshopped the Persuasion cast into a poster for the UK “comedy” series Carry On. For those who are unaware after they click the image, the Carry On series on UK streaming services have content warnings for racist and sexist stereotyping. This sort of meme humor is another easy way for heinous sentiment in fandom to slip under the radar with a jeering nudge and “joke.”

There has long been an established link between strict canonical interpretations of Austen and upholding white supremacist structures since well before Persuasion. Whether mainstream critics like it or not, there is a segment of Austen fandom that truly believes this necessary step toward racial inclusion is intolerable. There was even a previous racial backlash in fandom toward Sanditon, an adaptation of an unfinished Austen novel where Austen herself created Georgiana Lambe to be a Black heiress.

The focus of racial ire in that fandom turned to enforcing boundaries of who could participate in fandom. Those same elements of fandom also don’t like Bridgerton and Mr. Malcolm’s List for representing BIPOC as having money and status in the Regency, these two works are based on modern Regency romance novels and not Austen’s books. (Regency romance has its own history of racism which is interconnected.) This is also combined with many of Austen’s characters and the world around them having been built on slavery and colonialism.

The Jane Austen Museum at Chawton House has made strides to acknowledge this difficult history, but many in the UK media attacked the museum for it. The Black Lives Matter movement across Austen fandom and the Regency historical costuming community during June 2020 also brought into the light those who claimed their exclusionary tactics were motivated by religious fundamentalism. This was the result of such fans posting anti-Black Lives Matter posts on Instagram that were subsequently deleted. This context is key in understanding how fandom is interpreting Persuasion.

Closely related to this blatant racism, there is also the issue of driving away younger Austen fans. Many critics have argued that the modernization in the dialogue is “egregious,” but these are the sort of changes Generation Z viewers are going to appreciate. These pronouncements ignore that many of the changes are actually closer to history than expected and are also faithful to Austen’s spirit or intention.

“She’s a 5 in London but a 10 in Bath” correctly points out the fact Bath was a resort town far away from the bustle of London, plus the scarcity of eligible young women in that community. Witty observations of social structures are at the heart of Austen’s novels. An Austen historian pointed out on Twitter that the term “exes” first shows up historically in 1825, only a decade after the original publication of Persuasion. There are far worse anachronisms in all-white period dramas.

Austen gatekeepers also are attacking the framing of Anne’s melancholy about being forced to give up Wentworth. This also ties into the racism factor as Anne Elliot has been seen by many as a paragon of “white womanhood,” which would naturally exclude BIPOC and other marginalized groups. White women weaponizing their identity against BIPOC in fandom has been well documented in other fandoms, however it wasn’t until the Sanditon PineappleGate controversy that there was any attempt to document this in Austen/period drama circles. Many claim that Anne “wasn’t funny,” but they’re missing the point.

It’s clear the screenwriters of 2022’s Persuasion combined the dark humor many younger fans used to cope with the COVID-19 pandemic with the examples of Austen’s humor from the novel. Anne’s role as a caretaker for the ill along with her frustrations over her sister’s selfish ways resonates so much with our pandemic experience. These visual and dialogue queues were misinterpreted as Anne being a “girlboss.” A girlboss character would be taken seriously by the supporting cast around her, not as an awkward fifth wheel until her skills are deemed important by others. Anne’s calm when Louisa falls during the Lyme excursion, and Wentworth immediately praising Anne, is what proves the screenwriter actually “read the novel,” despite the condescending skepticism of some reviews.

Persuasion represents the new generation of adaptations that will borrow more cinematically and thematically from other adaptations plus other movies in general versus relying solely on Austen’s original novels. Joe Wright’s Pride & Prejudice (2005) is echoed in the costuming choices of Persuasion, and the cinematography and the modernized humor of the new film is clearly influenced by Autumn de Wilde’s Emma (2020).

Many reviewers have also compared Anne talking to the camera as reminiscent of Fleabag, but the comparison not only is a sly dig at recent pop culture trends younger viewers love but also ignores that there are examples of breaking the fourth wall during the historical Regency. Epistolary novels, or novels based on letters addressed to the general public to read, have the same function as a character talking directly to the camera. Austen’s earliest works, such as Love & Friendship, were examples of the epistolary format.

Some Austen fans are even angry at the thought that younger fans will find the modernizations in the movie approachable, such as this Tumblr post mocking the screenwriter for writing with their 13-year-old daughter in mind. How is this not the very definition of ageist gatekeeping in fandom? It’s depressing that I had to read hundreds of posts attacking the movie before I found someone excited for the film. Shouldn’t we be happy for and eagerly welcome Gen Z into Austen fandom?

“Jane Austen Is For Everyone” was a slogan BIPOC Austen fans came up with a few years ago, because literary societies, historical costume groups, and academic spaces were prioritizing white comfort over making antiracist reforms. The founders of that slogan also hoped that one day there would be adaptations that reflected race/ethnic diversity. Persuasion is the first wholly based on one of Austen’s novels to use racebent casting. While many media critics correctly pointed out this is a good thing, this fact in Austen fandom is intolerable. Racism in Austen fandom is defined by unspoken hostility, dog whistles, “tranquility,” and maintaining discussion spaces that fail to ban white supremacist sympathizers.

Although separating the fair critiques from the bad ones is difficult work, it must be done. If “Austen Is For Everyone,” that should indeed include BIPOC and fans who like Persuasion. More must be done to confront racism and gatekeeping in Austen fandom.