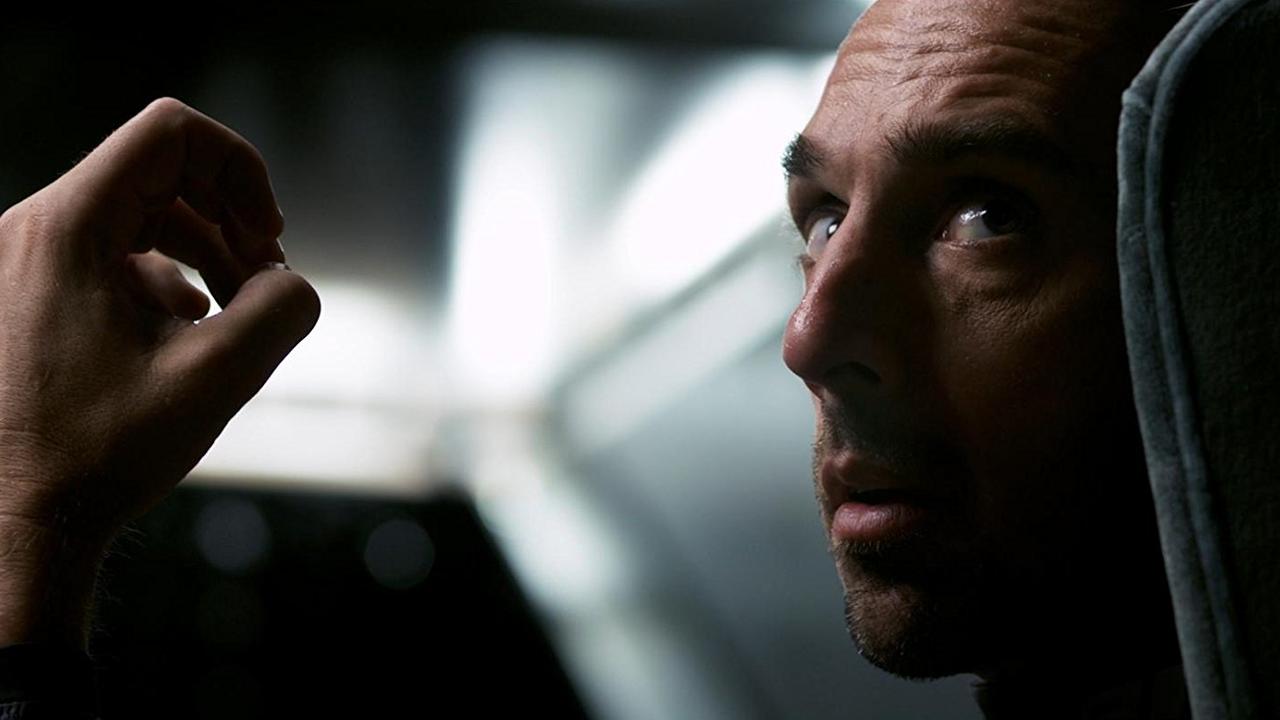

Infinity Chamber: exploring an underrated indie sci-fi gem

It’s claustrophic and keeps you guessing from beginning to end. We take a look at the superb indie sci-fi flick, Infinity Chamber...

This article comes from Den of Geek UK.

When astronaut Dave Bowman engaged in his battle of wits with the malfunctioning HAL-9000 in Stanley Kubrick’s seminal 2001: A Space Odyssey, the whole notion of humans interacting with computers on a mundane, conversational level was still in the realm of science fiction. Fifty years on from 2001’s release, and the film’s depiction of regular flights into space now looks more than a little far off the mark; its notion of an intimate relationship between humans and machines, on the other hand, still seems accurate.

The kind of artificial intelligence displayed by HAL hasn’t appeared yet, but computers are now such an intrinsic part of our daily lives that we’re seldom more than a few inches away from one. Voice-activated systems like Siri, Cortana and Alexa are all over the place; the phones in our pockets are now the modern equivalent of a Swiss army knife – they get us from place to place, help us interact with our friends, or order a mid-week takeaway. Given all the data and search requests we relatively plug into our devices, it’s often said that our phones and computers know us more intimately than we know ourselves.

In his typically eccentric documentary about technology and the web, Lo And Behold, filmmaker Werner Herzog asked several of his interviewees, “Does the internet dream of itself?” Unsurprisingly, nobody could quite formulate a reply, perhaps because it’s such a slippery question – is the internet like a huge collective unconscious, an Inception-like alternate reality we’re all connected to? If it isn’t already, will it become a huge hive mind, a shared dream, that we’ll one day dive into for good?

Maybe, maybe not. But what’s surely significant is how science fiction, whether on the silver screen or in the pages of a book, both anticipated the rise of computers and, in more recent years, started to explore what our changing relationship with machines might look like. Computers could talk fluent English long before Alexa; today, shows like Black Mirror are pondering the outcomes of death by social media or indescribably complex dating apps. It’s as though the possibilities of technology occupy our dreams long before they become a reality.

Technology, dreams, memory and reality form the backbone of Infinity Chamber, a 2016 thriller now available to stream on Netflix UK. Previously called Somnio, it’s a small, low-budget yet ingenious sci-fi film written and directed by Travis Milloy, who previously wrote the SF-horror mash-up, Pandorum.

Like recent genre hits like Moon and Ex Machina, Infinity Chamber’s story takes place on a tiny canvas: while standing in a coffee shop one day, average American guy Frank (Christopher Soren Kelly) is knocked unconscious by two armed assailants. He wakes up an unspecified length of time later in a sterile, futuristic-looking prison cell – the only thing approaching a home comfort is a slate-grey, reproduction armchair. Overcoming his confusion, Frank starts talking to a human voice emanating from a security camera in the ceiling, and learns that he’s suspected of being involved in some kind of hi-tech terrorism plot. Frank protests his innocence; the human voice, calling himself Howard, says it’s merely his job to oversee Frank’s ‘processing’, and doesn’t have any more information to give.

Gradually, Frank learns more about his prison cell: there’s a weird, whirling machine that somehow monitors his memories – forcing him to relive the same past experience over and over again in his mind, expecting that Frank’s subconscious will eventually give up a suggestion of guilt. Howard, meanwhile, is essentially a caretaker computer programme – the softly-spoken app that dishes out cups of coffee and soup from a vending machine, or opens the bathroom door so Frank can use the loo.

Infinity Chamber contains ideas seen in other indie sci-fi films, then – there are shades of Duncan Jones’ Moon, with its lone human protagonist and his AI companion – but they’re used to subtly different ends. There’s an ambiguity to both characters in Infinity Chamber, not to mention Frank’s history, relayed in flashback. Frank protests his innocence, but we’ve all seen enough thrillers to know that he may not be telling the truth. Howard, even once revealed as an AI, remains sympathetic to Frank, and constantly maintains that he’s just a machine doing his job. But can he really be trusted? Could even his glitches and occasional breakdowns be part of some psychological war being played in Frank’s mind?

All of this is played out in minimal, coolly-directed scenes that make the most of a low budget. The moment where Frank figures out that Howard’s a machine is a great piece of writing and acting; indeed, Kelly’s performance – lonely, frustrated, exhausted – effortlessly carries much of the film. The thriller part of the plot keeps us guessing, particularly when events turn to the moments leading up to Frank’s detainment, and his fleeting spark with a coffee shop owner, played by Cassandra Clark. As his understanding of the machine in his cell grows, Frank discovers a means of occupying his memories as though they’re the present; like a lucid dream, he’s able to converse with the coffee shop owner and, at least in his own mind, alter the course of events that have already occurred. But this merely leads to more questions: has he stumbled on a means of outsmarting the machine, or is this quite the reverse – the machine manipulating Frank to find out what it wants to know?

Thematically, Infinity Chamber’s paranoid atmosphere taps into our 21st century relationship with smartphones and the web. Modern technology comes to us with a smiling face; Twitter’s logo is a sky-blue bird; Alexa speaks to us with a soothing voice. All the same, there’s a wonder that these friendly apps, or at any rate the people behind them, might not have our best interests at heart. Just what are they doing with all that collected data, anyway?

Infinity Chamber also speaks to the hollowness that lies just behind our daily interactions with machines – the digital coldness that lies beneath the smile. Instead of interacting with shopkeepers at a checkout, we’re increasingly being asked to swipe our purchases through a machine. A friendly, pre-recorded voice thanks us for our patronage; all the same, it’s a numb, inhuman experience – another mundane human interaction rendered obsolete by progress. When Frank slumps into his chair, irked by Howard’s repetitions, it’s easy to sympathise.

Infinity Chamber, despite its tiny budget, is therefore a worthwhile companion piece to the whole HAL segment of 2001: A Space Odyssey.Watching both films certainly presents two possible scenarios in our growing reliance on technology. In 2001, HAL, at once a companion and guardian of a ship full of astronauts, goes terrifyingly rogue. In Infinity Chamber, the two pieces of tech Frank interacts with – Howard, the strange memory-manipulating machine – create a kind of good-cop-bad-cop dynamic. Howard ostensibly keeps Frank alive; the other machine is a kind of silent interrogator. It’s difficult to say which of the two is worse – it’s even possible that they’re both one and the same.

There’s lots of other stuff going on in Infinity Chamber, including the wider implication of a dystopian future America governed by machines and human agents who do their bidding. But Milloy’s thriller is at its best when its just Frank, alone in his cell, surrounded by unfathomable technology. Whether he intended it to or not, Milloy depicts a new, 21st century archetype here: Frank isn’t unlike any other westerner in 2018, cosseted and quietly probed by apps and search engines, relying on inventions he can scarcely understand and forging relationships with voices he’s never entirely sure he can trust.